Frustration: Mist obscured the view up the inlet to a Nunatak that would have shown them that it was a glacier

Unless stated, all distances are given in geographical (i.e. nautical) miles. One geographical mile equals 1.15 statute miles, or c.2,025 yards (1,852 metres). Temperatures are given in Fahrenheit and weights in imperial measures.

ONE

St Pauls, 14 February 1913

I am more proud of my most loved sons goodness than for anything he has done and all this glory & honour the country is giving him is naturally a gratification to a Mothers heart but very little consolation you know how much my dear son was to me, and I have never a bitter memory or an unkind word to recall.

Hannah Scott, 21 February 1913

Your children shall ask their fathers in time to come, saying What mean these stones?

Joshua IV. 21. Scott Memorial, Port Chalmers, New Zealand

IN THE EARLY HOURS of 10 February 1913, an old converted whaler crept like a phantom into the little harbour of Oamaru on the east coast of New Zealands South Island and dropped anchor. For many of the men on board this was their first smell of grass and trees in over twenty-six months, but with secrecy at a premium only two of her officers were landed before the ship weighed anchor and slipped back out to sea to disappear into the pre-dawn gloom from which she had emerged.

While the ship steamed offshore in a self-imposed quarantine, the officers were taken by the nightwatchman to the harbour masters home, and first thing next morning to the Oamaru post office. More than two years earlier an elaborate and coded arrangement had been set in place to release what everyone had then hoped would be very different news, but with contractual obligations still to be honoured, a cable was sent and the operator confined to house arrest until Central News could exploit its exclusive rights to the scoop the two men had brought.

The ship that had so quietly stolen into Oamaru harbour was the Terra Nova, the news was of Captain Scotts death on his return from the South Pole, and within hours it was around the world. For almost a year Britain had been learning to live with the fact that Scott had been beaten by the Norwegian Amundsen in the Race for the Pole, but nothing in any reports from the Antarctic had prepared the country for the worst disaster in her polar history since the loss of Sir John Franklin more than sixty years earlier. There is a dreadful report in the Portuguese newspapers, a bewildered Sir Clements Markham, the father of British Antarctic exploration and Scotts first patron, scrawled from his Lisbon hotel the following day, that Captain Scott reached the South Pole on January 18th and that he perished in a snow storm a telegram from New Zealand If this is true we have lost the greatest polar explorer that ever lived We can never hope to see his like again. Telegraph if it is true. I am plunged in grief.

If there had ever been any doubt of its truth in London, it did not last long, and with Scotts widow, at sea on her way to New Zealand to meet her husband, almost alone in her ignorance, the nation prepared to share in Markhams grief. Less than a year earlier the sinking of the Titanic had brought thousands to St Pauls Cathedral to mourn, and within four days of the first news from Oamaru the crowds were out in even greater force, silently waiting in the raw chill of a February dawn for a memorial service that was not scheduled to start until twelve.

There could have been nowhere more fitting than the burial place of Nelson and Wellington for the service, no church that so boldly embodied the mix of public and private sorrow that characterised the waiting crowd. During the second half of the old century Dean Stanley had done all he could to assert the primacy of Westminster Abbey, but as Londons Protestant cathedral, built by a Protestant for a Protestant country, St Pauls spoke for a special sense of Englishness and national election as nowhere else could. Within the Cathedral all is hushed and dim, recorded The Timess correspondent. The wintry light of the February morning is insufficient to illuminate the edifice, and circles of electric light glow with a golden radiance in the choir and nave and transepts. Almost every one attending the service is in mourning or dressed in sombre garments. Gradually the building fills, and as it does so one catches glimpses of the scarlet tunics of distinguished soldiers, of scarlet gowns, the garb of City aldermen, and of the golden epaulettes of naval officers shining out conspicuously against the dark background of their uniforms. The band of the Coldstream Guards is stationed beneath the dome and this, too, affords a vivid note of colour. Behind the band sit a number of bluejackets.

For all the trappings of the occasion, however, the statesmen, foreign dignitaries and diplomats, it was the simplicity of the service that was so striking. On the stroke of twelve the King, dressed in the uniform of an admiral of the fleet, took his place, and as the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London and the Dean of St Pauls processed with the other clergy into the choir, the congregation sang Rock of Ages. The Lords Prayer was then read, followed by the antiphon Lead me Lord in Thy Righteousness, and Psalms XXIII The Lord is My Shepherd and XC Lord Thou Hast Been Our Refuge.

It was a short service, without a sermon. Behold I shew you a mystery, Dean Inge read from 1 Corinthians XV:

We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed,

For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality.

So when this corruptible shall have put on incorruption, and this mortal shall have put on immortality, then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory.

O death where is thy sting? O grave where is thy victory?

As St Pauls ringing challenge faded away, the sounds of a drum roll swelled, and the Dead March from Saul filled the cathedral. For all those present this was a moment of almost unbearable poignancy, but with that ceremonial genius that the imperial age had lately mastered, the most memorable and starkly simple was still to come.

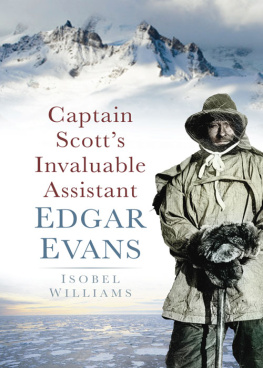

As the Prayer of Committal was read, the names of the dead Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates, Edmund Wilson, Henry Bowers, Edgar Evans filled the stricken silence of the dimly lit church with their absence. As we go down to the dust, the choir sang, just as they had done to the same Kieff chant at the memorial service for those lost on the Titanic, and weeping oer the grave we make our song: Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia! Give rest, O Christ, to Thy servants with Thy Saints, where sorrow and pain are no more, neither sighing, but life everlasting.

With a final hymn sung by the whole congregation, and a blessing from the Archbishop, the service was over. The National Anthem was sung to the accompaniment of the Coldstreams band, and as the sound reached the streets outside the vast crowd of some ten thousand still waiting took it up. The King was escorted to the south door, and to the strains of Beethovens Funeral March on the death of a hero, the congregation slowly dispersed.

For all its simplicity and familiarity, it had in some ways been an odd service, combining as it did the raw immediacy of a funeral with the more celebratory distance of a memorial. It might have been only four days since the news from Oamaru reached England, but by that time Scott and his men had been dead for almost a year, their bodies lying frozen in the tent in which they had been found. There is awe in the thought that it all happened a year ago, the