This book is dedicated to Gary Gregor whose knowledge about Edgar Evans and whose enthusiasm for the work has been a constant source of encouragement

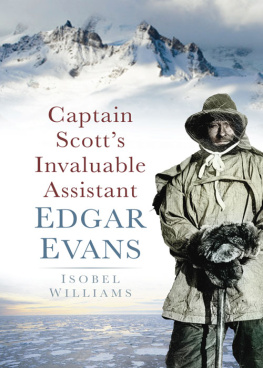

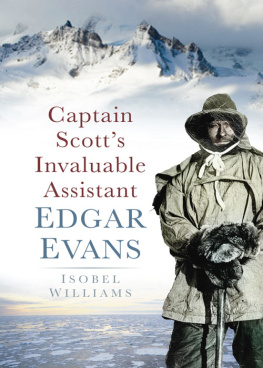

Front cover photograph: Edgar Evans dressed for exploration. (Courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute SPRI)

Contents

Dr David Wilson, the great-nephew of Dr Edward Wilson, Scotts confidant and friend, has been a remarkable source of friendship, encouragement and advice throughout the work. My colleagues, Dr John Millard, Dr Howell Lloyd and Dr Aileen Adams, have diligently read the work and offered helpful comments, as has Mrs Jackie McDowell.

Professor Stuart Malin has patiently guided me through the intricacies of longitude and latitude. Lieutenant Commander Brian Witts, Curator of HMS Excellent Museum, Portsmouth, assisted me with details of the field gun run competition at Olympia. I am greatly indebted to these colleagues and friends. I accept responsibility for any misunderstandings or omissions.

The assistance of the staff at the Scott Polar Research Institute, The Naval Museum at Portsmouth and the Swansea Library has been greatly appreciated; all have been unfailingly courteous, helpful and enthusiastic.

Alison Stockton and James Oram, a Classics Undergraduate at Durham University, have patiently proofread the work and I am grateful for their help.

I have to thank Professor Julian Dowdeswell, Director of the Scott Polar Institute, for permission to publish extracts from those manuscripts over which the Institute has rights, also the Debenham, Shackleton, Skelton and Scott families for kind permission to quote from family papers. The Auckland Institute and Museum of New Zealand have allowed me to quote from Charles Fords journals as have the Dundee Art Galleries and Museums in relation to James Duncans papers. Mr John Evans, Edgars grandson, has allowed me to quote from Edgars sledging journal. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders; any omissions or mistakes will be inserted into subsequent editions of this work.

Finally, my thanks must go to my husband, Dr David Williams, whose assistance and help made this work possible.

Saturday 17 February 1912, Antarctica.

A man crawls helplessly on the icy snow, his clothes are torn open, his skis are off, his gloves and boots lie discarded on the snow, bandages trail from his frostbitten fingers.

He dimly sees four images coming towards him, but in his confusion he cannot work out what is happening. When his companions arrive he can hardly speak. He can barely stand and after a hopeless attempt at walking he falls back onto the snow. Three of his exhausted rescuers plod back wearily to the camp for a sledge.

They lay him on the sledge and struggle to pull him over the snowy waste. On the way he loses consciousness. He is never to be aware of his surroundings again. In the tent, as his companions watch, his breathing becomes irregular and shallow; he dies quietly at 10 p.m.

So ended the life of Edgar Evans, the Welsh Giant from Middleton in South Wales, a man who contributed hugely to Antarctic exploration, a Petty Officer who had built a relationship with his leader, Robert Falcon Scott, that transcended the barriers of class, rank and education. Theirs was a loyalty that had been built over long periods of interdependence as they endured the horrors of prolonged man-hauling at sub-zero temperatures in Antarctica.

Scott wrote that Edgar was a giant worker with a truly remarkable head piece, He chose Edgar as one of the five to go to the Pole.

Edgar died on the return, overcome by circumstances so awful that his four companions were soon to join him in icy tombs in Antarctica.

This is Edgar Evans story.

Notes

Ed. King, H.G.R., Edward Wilson Diary of the Terra Nova Expedition to the Antarctic 19101912, Blandford Press, London, 1972, p. 243.

Ed. Jones, M. Robert Falcon Scott Journals Scotts Last Expedition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005, p. 369.

Ibid., p. 303.

1

Edgar Evans came from the Gower Peninsula in South Wales. Jutting into the Bristol Channel and open to the Atlantic gales, Gower is a place of outstanding natural beauty, a location that attracts visitors to its shores year after year. It boasts other famous attractions: in one of its coastal caves, the Paviland Cave, the oldest human skeleton in the British Isles was discovered the Red Lady of Paviland (actually male remains) is tens of thousands of years old.

It would have been a remarkable astrologer who foretold fame for Edgar Evans when he was born on 7 March 1876 in Middleton Hall Cottage, Middleton a village in Rhossili and one of the remote parishes on the peninsula. Edgars mother, Sarah, had moved to Middleton Cottage, her sisters home, for her confinement.

This was a modest family. Their roots were firmly in Gower. Evans paternal grandfather, Thomas, and three previous generations of his family, came from the peninsula. Thomas was employed in a local limestone quarry (limestone was shipped across the Bristol Channel to fertilise the fields of north Devon). Thomas son, Charles (18391907), the father of Edgar Evans, was one of the famous Cape Horners, hardy seamen who sailed from Europe around Cape Horn to the west coast of America, a journey that could last six months.

The Cape Horn trade grew because Swansea was then the world centre for smelting copper, essential in industry, construction and ship-building (the copper covering on ships hulls prevented the wood from rotting and made the vessels faster).

There were copper works in Swansea from as early as 1717. Approximately 2 tons of coal was necessary to smelt 1 ton of copper, and since South Wales was rich in coal, copper was brought to Swansea rather than coal being taken to the copper sources. When British ore was worked out, copper mines further afield were sought and Cuba and South American countries, particularly Chile, were used. These voyages to South America, in coal-carrying sailing ships, were hazardous undertakings. Life at sea was brutal and unforgiving. Off the Horn, with winds at full-gale strength, waves as high as the maintops, sometimes hail and then snow coming down thick, clouds so low they enfold the mastheads, spume and sky indistinguishable,

But Charles Evans pursued this trade until he was in his mid-30s, well after the time he married and had children. In 1862, when he was 23, Charles, described as Mariner, son of Thomas Evans, Quarryman, married Sarah Beynon in St Marys church, in the village of Rhossili. Rhossili is one of the many villages dotted over Gower. It had 294 residents marriage and her family had held the licence for the Ship Inn for most of the nineteenth century.

The ceremony was performed by the Reverend John Ponsonby Lucas BA, MA, an Oxford graduate, who ministered to several of the local villages. St Marys, with its beautiful Norman doorway, remains an active, functioning church. For many years a plaque in the aisle wall has proudly commemorated the life of Charles and Sarahs famous son, Edgar.

As was usual in Victorian households, the couple produced a large family there were eight known children. Birth control was unknown in working class communities in the late 1800s, and a high birth rate was a type of insurance policy against an unsupported old age. Four of the children are listed in the 1871 census: Charles, 7; John, 4 (both described as scholars); Mary-Ann, 2; and Annie Jane aged 1. The gap of three years between Charles and John suggests an infant death. In 1874, another son, Arthur, was born, followed, in 1876, by Edgar. A seventh child, George, was born in 1878 and a sister, Eliza Jane, in 1879. In fact Sarah Evans gave birth to more than the eight children; in 1913, after Edgars death, she was interviewed by a local reporter, and exhibiting stoicism difficult to imagine nowadays, she said that she had buried nine of her twelve children, three having died from consumption.

Next page