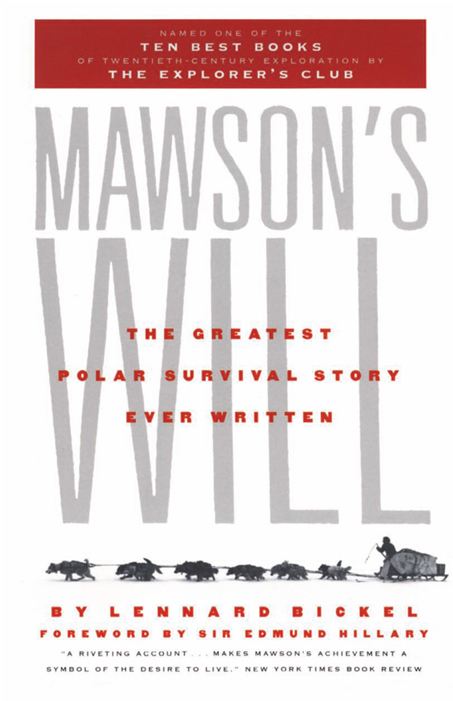

Copyright 2000 Lennard Bickel

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press L.L.C.

25 Lebanon Street

Hanover, New Hampshire 03755

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bickel, Lennard.

Mawson's will: the greatest polar survival story ever written / Lennard

Bickel; foreword by Sir Edmund Hillary. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Stein and Day, 1977.

ISBN 1-58642-000-3 (alk. paper)

1. Mawson, Douglas, Sir, 18821958 Journeys. 2. Australasian

Antarctic Expedition (19111914) [1. Antarctica Discovery

and exploration Australian.] I. Title.

G875.M33 B53 2000

919.89 DC21 99-059210

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN-13: 978-1-58642-000-0

FIFTH PRINTING

Contents

To Frances Craighead,

who opened a door

Foreword

T he heroic period of Antarctic exploration occurred in the score of years at the beginning of this centurya surprisingly short time ago when you think of how long man has been exploring his planet.

It was in that time that men first commenced their resounding battles, with all the incredible discomforts and hardships of the southern continent, and the period was dominated by the names of Amundsen, Scott, and Shackletonand mighty men they were, too.

But there were others like these great heroes, who were undertaking comparable feats of courage and leadership, who never achieved quite the same stature in the public mind because their objectives did not include that magic goalthe South Pole. Outstanding among these men were two Australians, middle-aged Professor Edgworth David and Dr. Douglas Mawson (later Sir Douglas). Their 1908 man-hauling sledge journey to the South Magnetic Pole along with the Sydney medico Dr. Alistair MacKay was a tremendous undertaking; it was on the return journey of some hundreds of miles of desperate travel back to the seacoast that Mawson showed to the full the strength, vitality, and leadership that were so pronounced a part of his character.

But Mawson had an even greater test ahead of him. From 1911 to 1913at the same time as the Scott tragedy was coming to its sad conclusionMawson led his Australasian Antarctic Expedition into the unknown country west of Cape Adare. It was an expedition that carried out a notable amount of scientific research, which earned it a place among the great scientific expeditions of its day.

However, the most dramatic events had nothing to do with science. They involved a man's battle against most appalling natural obstaclesMawson's own fight with death as it is related in this book.

Some 320 miles east of Commonwealth Bay (which Mawson discovered), a companion crashed into a deep crevasse with their tent, all the man food except one week's sledging rations, all the dog food, and most of their equipment. With his other companionwho was also doomedMawson's journey back to winter quarters was a terrible struggle. It became what is probably the greatest story of lone survival in Polar exploration.

That he survived at all was due only to his tremendous spirit and determination. Mawson earned his place of honor as one of the great men of the Antarctic.

Sir Edmund Hillary

Sydney, 1976

Prelude

The Two Tents

T he tents were a thousand miles apart. Between them was an awesome waste of ice-clad mountain ranges, huge glacial valleys, wide upland snow plains swept by polar wind; yetseparated as they werethey were tightly linked in the saga of the Antarctic.

Three men lay in each tent. Both tents were cut from green canvas, but the one in the southeast, pitched on the vast floating wasteland of the Ross Ice Shelf, could not be seen. It was completely covered by the compacted snow of a long winter. It was quiet and still inside that tent. Not so in the shelter on a high ice plateau in the northwest. There, three men stretched out in reindeer-skin sleeping bags and listened to the howl of a ferocious blizzard, which slapped and banged the canvas cover against the bamboo poles. It was so noisy they could communicate only by shoutingbut by now there was little left to say.

For two days they had huddled down trying to keep warm, trapped on the exposed plain while the winds from the polar plateau rushed unimpeded across the bottom of the world and filled the air with racing drift and stinging ice crystals. In that dense gloom, they had neither night nor day, and the hours were a long painful crawl. The winds were so strong that they could not ignite their kerosene-fed primus stove, and, unable to melt snow for drinking water or to heat food, they waited in their bags and endured thirst and eased hunger by nibbling hardtack and small sticks of plain chocolate, listening always for some sign of a lessening in the gale.

Each one of these three men might easily have been in the other tent. Most certainly the leader of this trio and leader of the whole expedition, Dr. Douglas Mawson, would have been had he not resisted strong pressure to abandon his own plans. But for his two companions, he knew, it was a second choice. Both of them had originally sought to join the other party andmissing selection narrowlyhad been warmly recommended to Mawson. He had found them first-class men, ideally suited to their allotted tasks, and so had been glad to appoint them.

Mawson was already an Antarctic veteran at the age of thirty, tall and powerful, a commanding leader and experienced geologist. He was encamped with two men from different countries and with different backgrounds. Lieutenant Belgrave Edward Sutton Ninnis of the British Royal Fusiliers, scion of an old Cor nish tinmining family, son of a London doctor, was unassuming, patient and loyal, and good with animals. Dr. Xavier Guillaume Mertz, a German-speaking law graduate from the Swiss city of Basel, was at twenty-eight years of age a ski champion and fine mountaineer.

Ninnis and Mertz had become firm friends since they joined this expedition in London as joint handlers of the thirty Greenland husky dogs and crossed the world together on a long, slow voyage, tending and nursing the animals on the open deck. Now the dogs were snuggled down in the snow with only their muzzles showing. Both dogs and men waited for the wind to die and the air to clear so that they could set their faces eastward and move into the unknown wilderness. All three men were strong, determined, conditioned by hard work in the long dark months of winter, impatient to open their journey of discovery.

Into the afternoon of that second day the gale blasted from the hinterland, and the rivers of snow filled their world with white, frenzied chaos while they lay waiting under the rocking tent, cold, thirsty, hungry.

Over the tent in the southeast, the afternoon was clear, calm, and still, and a low sun bounced its vicious glare across the 250,000 square miles of the white wastes of the Ross Ice Shelf. It was a day to be engraved in polar history, a day of sad discovery. Ten men, with two ponies and two dog teams, had plodded into the glare since early that morning; for almost twelve hours they had trudged southward.

The searching ended when they found the cone of snow and beneath it the tent that had gone to the South Pole. Now it was a frozen sarcophagus. Under the snow's weight, the tent walls sagged over the bodies of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, Dr. E. A. Wilson, and Lieutenant Henry Bowers. Diaries with the bodies told the now classic tale of the crushing blow of finding Amundsen had reached the pole weeks before them, of the struggle back in which two of the party of five had perished. Now here were the three of them dead only eleven miles from food and fuel at One Ton Depot.

Next page