| The ABC Wave device is a trademark of the

Australian Broadcasting Corporation and is used

under licence by HarperCollins Publishers Australia. |

First published in 2010

This edition published in 2012

by HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Diana Patterson 2010

The right of Diana Patterson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000 .

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 , no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

HarperCollins Publishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

31 View Road, Glenfield, Auckland 0627, New Zealand

1A Hamilton House, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001, India

7785 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8JB, United Kingdom

2 Bloor Street East, 20th floor, Toronto, Ontario M4W 1A8, Canada

10 East 53rd Street, New York NY 10022, USA

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Print data:

Patterson, Diana, 1950

The ice beneath my feet / Diana Patterson.

ISBN 978 0 7333 2423 9 (pbk.)

ISBN 978 0 7304 4542 5 (epub)

Patterson, Diana, 1950

Women scientists Antarctica Biography.

Women Antarctica.

Women Employment Antarctica.

Women explorers Antarctica.

500.82092

Cover design by Matt Stanton

Cover images background ice image by Shutterstock.com; all other images courtesy of the author

To my fellow 1989 Mawson winterers

Antarctica is a source of fascination to so many people. The proliferation of documentaries, books and opportunities for personal travel does not seem to have diminished the response I get when I talk about my experiences of living and working in Antarctica. Two decades have now passed since I made my first voyage, of what now numbers 16, across the stormy Southern Ocean to Antarctica. Over that time I have been asked by many people to write about my adventures, to record my stories. Apparently not satisfied with just the stories of the leaders of the heroic age of Antarctica, of Scott, Shackleton, Amundsen and Mawson, or the stories of the modern day adventurers who are in a variety of ways attempting to put their own name in the history books, I find that there is interest too in my story as the first woman leader of an Antarctic research station. So for all the people I have talked to over the years at schools, corporate functions, from the flight deck of a 747 aircraft as we take a day sightseeing flight to Antarctica or more recently on an expedition cruise ship, why, after all this time, have I finally responded to your request for more stories?

It has taken so long because when I returned from my stays in Antarctica, I felt it might be perceived as though I was trying to put myself above and apart from my Antarctic contemporaries. I didnt want to be seen as a tall poppy, with all of the negative connotations that went with that label. Like most of the pioneering women who first worked on the Antarctic continent in the 1980s I had tried my best to promote the presence of women in Antarctica as normal and nothing unusual, though indeed it was. The more compelling reason for the delay is that I thought writing about my time as a leader in Antarctica might prove to be a career limiting move. My story would certainly have been somewhat different if I had told it 20 years ago, with many events ignored or glossed over. As it was I both benefited from and was disadvantaged by my Antarctic service. Experience as a woman Antarctic station leader was unusual enough to arouse curiosity, so I was invariably short-listed for diverse and unusual jobs, but at the same time I found that some senior managers were quite threatened by me and my experience of management in such a remote workplace. I told myself that this negativity was not about me, it was about them. In many cases the most exciting thing they had probably done in their life was trying to cross a busy road in rush hour. I did not think it would be to my advantage for such people to know that I had been the navigator for a journey venturing 400 kilometres inland on the Antarctic plateau, or that I had run with sledging dogs 350 kilometres on the frozen ocean around the coast of Antarctica never mind the more outrageous activities! Having fulfilled any ambitions I had for my career, concern for an adverse reaction is no longer relevant.

This is not a story from the heroic era of Antarctica, its not an adventure story about a four-week expedition to the South Pole; instead, it is a story about a dream of working in Antarctica, one which evolved into wanting to be the leader of an Antarctic research station. With the benefit of hindsight one might say it was an unrealistic dream given that when it was formed in my mind women had not yet been included on the annual expedition teams on any of Australias three Antarctic continental research stations. However, like many other young women in the 1970s, I believed women could do anything! An enlightened family and, of course, the emerging womens movement made this possible. It did take time, almost eight years, to realise my goal which, once achieved, far exceeded my expectations.

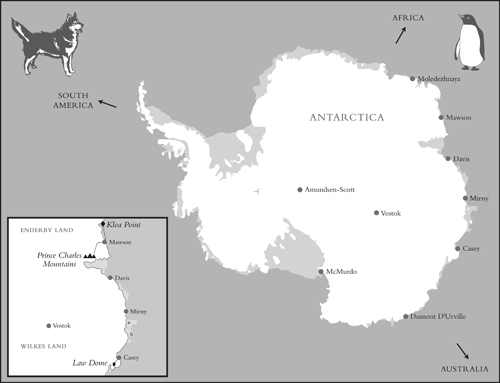

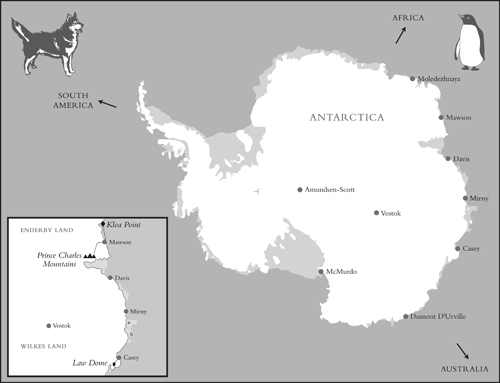

My story captures a time when a new era was occurring with the human presence in Antarctica. It came long after that first Age of Discovery with its great sea voyages and quest for the great south land, and almost 100 years after man first set foot on the Antarctic continent in 1895, thus beginning what is known as the Age of Exploration or the Heroic Age. This period encompassed the time of the race to be first to reach the South Pole, with epic stories of both survival and of disaster. Following the First World War private expeditions continued in a new Mechanical Age as aeroplanes and motorised vehicles were used to extend the exploration of the icy continent. In the decade following the Second World War the United States of America launched the first of the government expeditions by circumnavigating the continent, mapping the coastline as they went. The next era, the Age of Science, was firmly established when, by the International Geophysical Year of 1957, 12 countries had established a cooperative approach to scientific research at 40 Antarctic bases and at a further 20 bases on the sub-Antarctic islands.

My story begins in 1979 when I developed the ambition not only to be a woman working in Antarctica but to be the leader of one of Australias research bases. While a national presence in Antarctica with a focus on science remained, it was also a time of change in Antarctica, though not necessarily a new age. The make-up of the research stations was a major part of this change, with modernisation resulting in tradesmen outnumbering scientists and other support staff. Women were beginning to make their presence felt with their inclusion in overwintering populations, spending up to 12 months in Antarctica. In fact, five Americans and one New Zealand woman had wintered by 1980. It was not until 1981 that the first Australian woman, Dr Louise Holliday, wintered at Davis station. By 1987 when I finally achieved my ambition to work in Antarctica, only ten women had wintered on Australian bases, six at Mawson, three at Casey and one at Davis.