ALONE

ON THE ICE

The Greatest

Survival Story

in the History of

Exploration

DAVID ROBERTS

For Sharon

without whose love and support

I would not be a writer today

CONTENTS

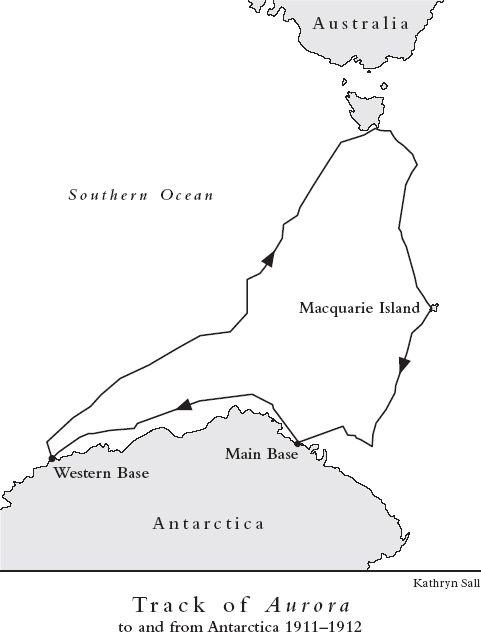

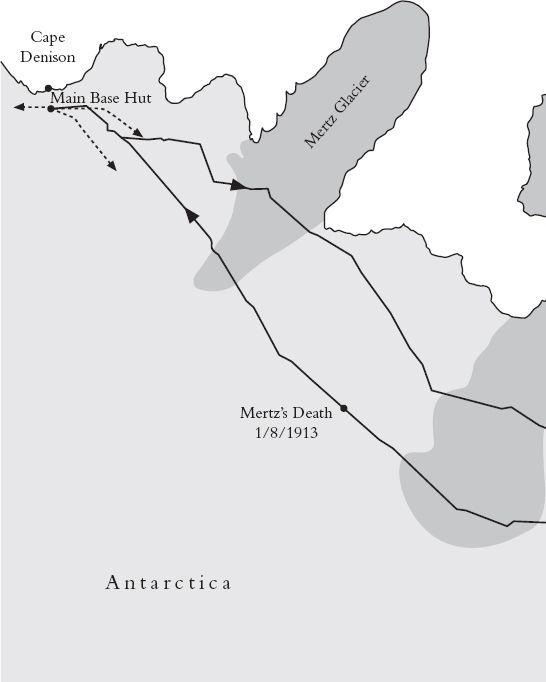

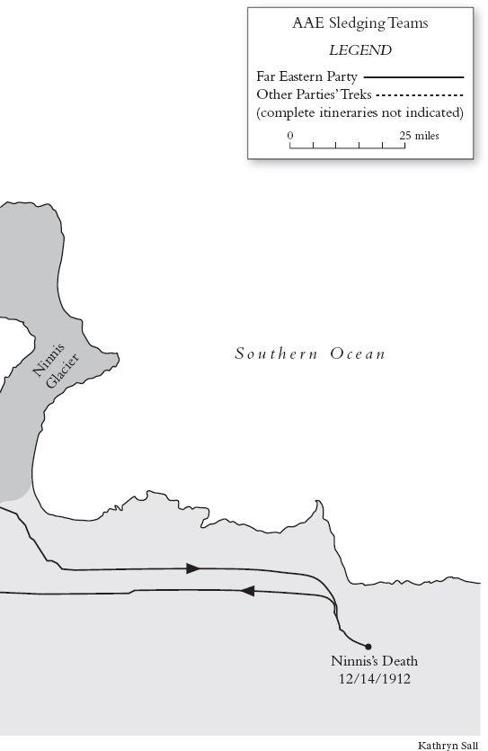

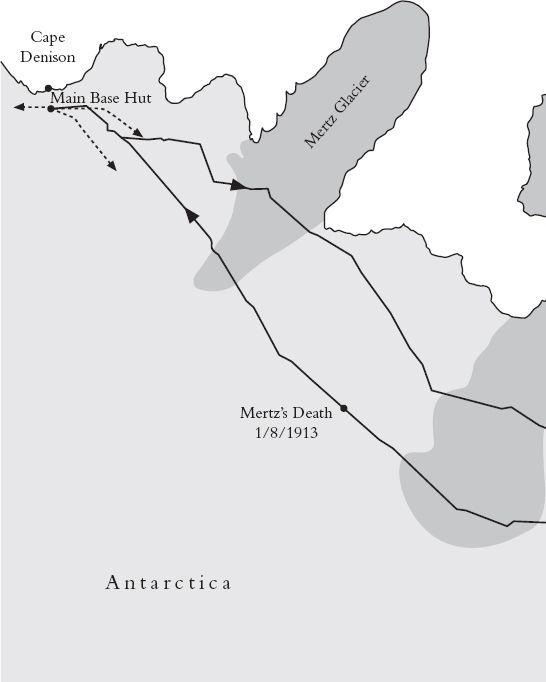

I t was a fitful start to the most ambitious venture ever launched in Antarctica. After eight days of arduous toil on the featureless plateau of snow and ice, the three men were camped only 20 miles from their base, the sturdy hut at Cape Denison in which the whole party had wintered over during the previous ten months. Those eight days had been plagued by backtracking trips to relay loads, by constant tinkering with balky gear, and by a two-day storm with gales so strong the men could not budge from their tent.

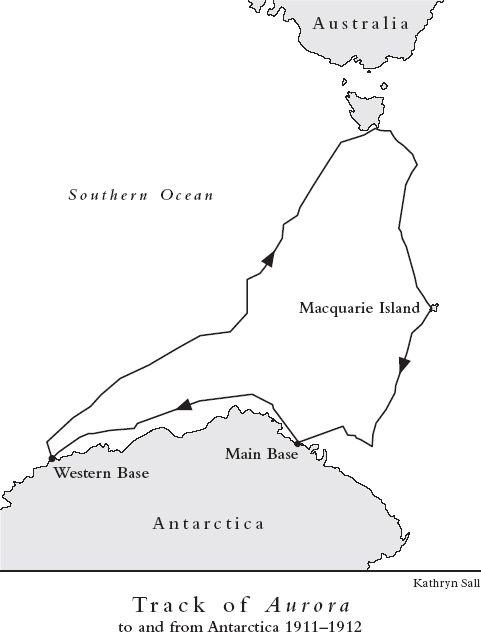

The date was November 17, 1912. Douglas Mawson, leader of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE), was a thirty-year-old lecturer in mineralogy and petrology at the University of Adelaide in South Australia. He was already the veteran of one expedition to the southernmost continent, during which he had served heroically from 1907 to 1909 under the command of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Mawsons tentmates were Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz. Born in London, a twenty-five-year-old lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, Ninnis had Antarctica on the brain, having unsuccessfully applied for Captain Robert Falcon Scotts Terra Nova expedition shortly before Mawson snatched him up for his own team. Mertz was a twenty-nine-year-old lawyer from Basel, Switzerland, as well as a highly accomplished skier and mountaineer.

Among the eighteen hands who had spent the first year in the Cape Denison hut, which the men called Winter Quarters, both Ninnis and Mertz were exceptionally well-liked. Ninnis had been nicknamed Cherub by the crew, partly on account of his complexion, recalled one teammate, which was as pink and white as that of any girl. He was tall and rather ungainly in build, and had more boxes of beautiful clothes than seemed possible for one mere man.

In the best-known portrait of Ninnis, he sits in full uniform, hands clasped on the hilt of his sword, as he looks upward with a serene and innocent gaze. An eloquent diarist, Ninnis recorded in a breathless outburst his incredulity at finding himself in Antarctica only days after the ship made landfall at Cape Denison in January 1912:

From the creation the silence here has been unbroken by man, and now we, a very prosaic group of fellows, are here for an infinitely small space of time, for a short time we shall litter the land with tines, scrap timber, refuse and impedimenta, for a short time we shall be travelling over the great plateau, trying to draw the veil from a fractional part of this unknown land; then the ship will return for us and we shall leave the place to its eternal silence and loneliness, a silence that may never again be broken by a human voice.

Xavier Mertz was nicknamed X by his teammates, who teased him throughout the expedition on account of his uncertain command of English, German being his first language. He was much admired, however, for his skill on skis (one teammate hailed him as a magnificent athlete), for his sense of humor, and for his skill at making omelettes out of penguins eggs, on which the whole team feasted on the eve of their departure from Winter Quarters.

In a studio portrait, Mertz sports the bushy mustache of an alpine montagnard, while his sidelong gaze seems to project both wariness and intelligence. His diary, written in German, is plainspoken, with occasional flights of reverie or passion. On November 17, 1912, despite the disheartening start of the journey across the plateau, Mertz recorded his dawning joy at the prospect of discovery in a brief passage akin to Ninniss outpouring from the previous January: from now our route goes farther on, into unexplored land, which no human eyes have yet seen.

Over the winter, Douglas Mawson had proven himself to be a firm leader who detested idleness and demanded the maximum of effort from his men. Yet he had also won unstinting loyalty from all but one or two, for he had worked harder than all of them, chipping in to help with the most onerous and dangerous of tasks. An innate tendency toward aloofness was tempered by his personal charm. Unlike Scott, who on his expeditions preserved the distinction between officers and men with a naval rigor that extended to separate messes on shipboard, Mawson fraternized constantly with his teammates, ate with them at a communal table, and both gave and sought advice at every hand.

Lean, six feet three inches tall, with piercing blue eyes, Mawson cut a striking figure at the age of thirty. In his own way he was as strong and athletic as Mertz, and his endurance and capacity to withstand pain would become legendary. The best-known studio portrait of Mawson, taken in 1911, reveals an impossibly handsome face, with just the hint of a receding hairline. In the photo Mawson holds a penetrating gaze that proclaims his calm composure and adamantine will.

A certain reserve also stamped the mans character. There is little or no evidence of any women in his life before the age of twenty-seven, when, at an outdoor dinner party in the Australian mining town of Broken Hill, he met a seventeen-year-old beauty named Paquita Delprat. She was the well-born daughter of Dutch parents, with an admixture of French and Swiss on her mothers side. It was love at first sight on both sides, although a year would pass before they met again. In December 1910, they became engaged, but their marriage would be postponed until after the completion of the AAE.

Throughout the expedition, Mawson wrote letters to Paquita, even though he knew it would be months before she would be able to read them. And from the Netherlands and Australia, Paquita wrote her own letters, even as her fears about her beloveds safety grew and darkened in what she called this everlasting silence.

Just an hour before his departure on the great overland journey that would win Mawson his lasting fame, he wrote to Paquita from the hut on November 10:

I have two good companions Dr Mertz and Lieut Ninnis. It is unlikely that any harm will happen to us but should I not return to you in Australia please know that I truly loved you from an admiration of your spirit....Good Bye my Darling may God keep and Bless and Protect you.

S ince the second decade of the twentieth century, Mawson has lurked in the shadow of his contemporaries Scott, Shackleton, and the great Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen. In part this is because he was Australian. (Though born in England, Mawson emigrated to New South Wales with his family at the age of two.) But the greater reason for the neglect of Mawson and the AAE lies in the fact that, unlike nearly all the Antarctic explorers of what is called the heroic age (18971917), Mawson was completely uninterested in reaching the South Pole. What mattered to the man insteadand what drove the vast ambitions of the AAEwas the urge to explore land that had never before been seen by human eyes, and to bring back from the southern continent the best science that men in the field might be capable of.

Next page