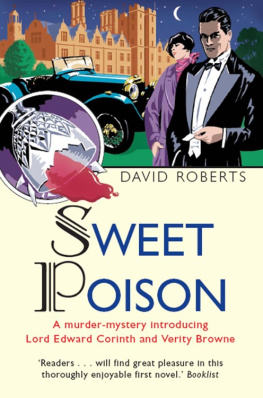

D AVID R OBERTS was a publisher for thirty years before becoming a full-time writer. He is married and divides his time between London and Wiltshire.

Praise for David Roberts

A most engaging pair of amateur sleuths whom I look forward to encountering again in future novels.

Charles Osborne, author of

The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie

Roberts use of period detail... gives the tale terrific texture. I recommend this one heartily to history-mystery devotees.

Booklist

The plots are exciting and the central characters are engaging, they offer a fresh, a more accurate and a more telling picture of those less than placid times.

Sherlock

Titles in this series

(listed in order)

Sweet Poison

Bones of the Buried

Hollow Crown

Dangerous Sea

The More Deceived

A Grave Man

The Quality of Mercy

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 2005

This paperback edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 2006

Copyright David Roberts 2005

The right of David Roberts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-1-84529-317-8 (pbk)

ISBN-10: 1-84529-317-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-84529-128-0 (hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-84529-128-X

eISBN: 978-1-78033-419-6

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Olly

Romeo: Courage, man; the hurt cannot be much.

Mercutio: No, tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church door; but tis enough, twill serve: ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man.

Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

Give me the daggers. The sleeping and the dead

Are but as pictures.

Shakespeare, Macbeth

August 1937 February 1938

In England, when a great public servant dies, it is customary to hold a memorial service in Westminster Abbey at which his achievements are recalled and his sins forgiven if not forgotten. Death transforms a hated rival into a cherished colleague whose loss is genuinely felt, reminding the survivor of his own mortality. Like the Roman general enjoying his triumph, a slave whispers in his ear, Respice post te, hominem te memento! Look behind you and remember you are mortal. If called upon, the mourner composes a panegyric replete with platitudes.

At the Abbey, he removes his top hat with studied dignity, gives his name to the usher and wonders how far down the list it will appear in the following mornings report in The Times and the Morning Post. He sings an anthem and listens poker-faced to the eulogy. It is not a long service because the congregation is made up of busy and important men whose time is money. As the organ sounds in sombre magnificence he processes out, proud to be one of us. He feels a stirring of excitement in the knowledge that soon he will be mingling with the high and mighty on equal terms. At the Abbey door, he whispers a few words of comfort in the widows ear, gives the eldest boy a firm handshake and pats the youngest on the head and, his duty done, replaces his top hat. He raises his eyes and sees many friends and acquaintances whom he greets with a sad smile and a modest nod of the head. Gradually, back in the world of the living, spirits lighten and his smile broadens. He makes what he hopes are unnoticed efforts to put himself in the way of those higher in rank or in a more exalted office with whom he can speak a few words and be seen to be doing so. It is the way things are done, at least in England.

In the case of Lord Benyon, the economist, writer and government servant, who had been killed when the giant airship, the Hindenburg, had exploded in a ball of fire as it attempted to dock in New Jersey, the situation was a little different. For one thing there was the extraordinary nature of his passing. In the second place Benyons only living relative was a sister married to a self-important stockbroker. There was no black-veiled widow or desolate children upon whom the mourners could focus their grief and, though no man is without enemies, Benyon had far fewer than most. Even Montagu Norman, the Governor of the Bank of England and an old sparring partner, admired Benyons abilities and liked him as a man though he abhorred his ideas.

The Prime Minister and senior cabinet ministers filled the front pews along with the Court of the Bank of England, the American ambassador, the Provost and Fellows of Kings College, Cambridge, leading British financiers and other dignitaries. There was a certain irony, which Benyon would have relished, that he should be mourned by a political class he had long derided and in a religious service he had been known to describe as hocus-pocus. For all that, he would surely have been delighted to see so many friends gathered to say their farewells. These friends were a very mixed bag as his interests had extended far beyond politics, economics and business. His wife, Inna, who had died a year before, was a prima ballerina in her youth and had danced for Diaghilev. Many of her friends from the world of ballet had become his friends: dancers and choreographers such as Anton Dolin, George Balanchine and Lydia Lopukhova. His close friends included Sir Thomas Beecham, director of the Royal Opera House, writers and artists such as Virginia Woolf, Morgan Forster and Duncan Grant, as well as actors and theatre directors. Women had loved to confide in him despite his feeble physique, weak eyes hidden behind thick-lensed spectacles and balding head, so it was no surprise to find the Abbey filling up half an hour before the service was due to begin.

It was early August and the great church was almost hot and certainly stuffy. The Hindenburg had been destroyed in May when the Abbey was being decked out for the coronation; it was only now that it had regained its normal sober dignity and was ready to give death its due. The House of Commons was about to rise for the summer recess, and politicians and civil servants were on the point of departing for the grouse moors or to take what many believed would be their final holidays on the Continent before the outbreak of a new European war.

Among the many hundreds who had gathered to pay their respects were Lord Edward Corinth and the journalist, Verity Browne. They had found seats way back in the nave where they could see nothing and hear very little. Verity, as a committed Communist and atheist, normally refused on principle to enter a church but on this occasion had swallowed her convictions out of affection for Benyon. In the short time they had known him, both Edward and Verity had come to look upon him as a dear friend. Edward had acted as his protection officer aboard the Queen Mary on a recent trip Benyon had made to the United States to try to persuade President Roosevelt to fund Britains rearmament programme. Benyon had been unsuccessful, as he feared would be the case, but had at least survived an attempt on his life. Furthermore, he was a bad sailor and the ship had not been as stable as Cunard had promised. A storm in the Atlantic had prostrated him and he had declared that on the next occasion he had to visit the States he would travel by air. The Hindenburg had made several safe crossings and its only disadvantage seemed to be that, as an enemy of Fascism, Benyon hated to travel in an airship adorned with the swastika.

Next page