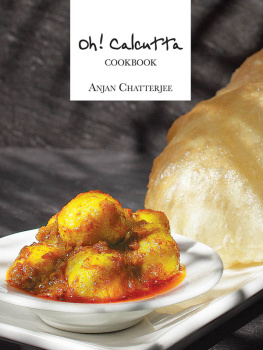

ANJAN CHATTERJEE

RANDOM HOUSE INDIA

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection published 2011

Copyright Anjan Chatterjee 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-8-184-00115-0

This digital edition published in 2017.

e-ISBN: 978-8-184-00249-2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This book is dedicated to the 18 million Chinese food fanatics who have made Mainland China what it is today.

Contents

Confucius Says...

Everyone eats and drinks, said Confucius, but few can appreciate taste. For centuries, Chinese scholars studied the nature of taste, and their food, as a result, is one of the most sophisticated in the world.

But my first encounter with Chinese food, as will be the case with most readers of this book, was not quite as refined. The Chinese food I grew up with during the 70s was IndianChinese, churned from the kitchens of Tangra, the immigrant Chinese neighbourhood of Kolkata. It was delicious but it wasnt, I am afraid, the real thing. I read a very funny story recently where a Chinese delegation to Kolkata was treated to a special TangraChinese meal by their hosts. At the end of the meal the delegation were asked what they thought of their dinner; they remarked it was the best Indian meal they had ever had.

So if Chinese food isnt chilli chicken and vegetable Manchurian, what is it? Like Indian food, there is really no such thing as Chinese food. Instead it varies from region to region (more of this in the following pages). But it does have common principles.

Firstly, all Chinese food follows the principles of yin and yang, i.e. of balance. Very few Chinese dishes consist of only one single ingredient, as it offers no contrast and so lacks harmony. This is the core of the Taoist philosophy of yin and yang. So, with few exceptions, all Chinese dishes consist of a main ingredient (chicken, fish, tofu, Chinese greens, asparagus, aubergine) with one or several supplementary ingredients like capsicum, mushroom, carrots, etc. in order to give the dish the desired harmonious balance of colour, aroma, flavour, and texture.

This principle of harmonious contrast is carried all the way through a meal. No Chinese would serve a single dish on his table, however humble his circumstances might be. The order in which different dishes are served, either singly or in pairs (often in fours) is strictly governed by the same principles: avoid monotony and do not serve similar types of food one after another or together; instead use contrasts to create a perfect harmony.

Chinese cooking also pays special attention to the four facets which they believe make up taste. The first is colour. Each ingredient has its own hue. Some change when cooked, others only reveal their colour when contrasted with foods of other colours. For example, chicken, particularly the breast meat, combines well with the bright greens and reds of the capsicum.

The second is aroma. Aroma and flavour are very closely related to each other, and they both form an essential element in the taste experience. Chinese cooking most often uses agentsspring onions, root ginger, garlic, and winethat they believe bring out the true aroma of certain ingredients.

The third is flavour. Each region has its own classifications of flavours, but out of the many subtle taste experiences, the Chinese have isolated five in particular: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and piquant, and often these flavours are combined to contrast with each other. Take the famous sweet and sour sauce, a characteristic of Shanghai cuisine, for example. Or lamb with bitter melon, where the sweetness of the meat balances the bitter melon. These contrasts also sometimes have other uses. In the case of the lamb dish, the bitter melon (yin) balances the high cholesterol level of the lamb (yang).

Texture is the final vital element in Chinese cooking. A dish should have one or several textures: tenderness, crispness, crunchiness, smoothness, or softness. The selection of different textures in one single dish is as important as the blending of different flavours and the contrast of colours. So, for example, the pale coloured, jelly-like tofu is combined with the crisp, green celery, and then accented with dark shiitake mushroom and pale yellow bamboo shoot.

I had no chance to experience this kind of Chinese food growing up, although, being a foodie and an amateur cook, I never stopped dreaming of it. One day, using up all my lifes savings, I set off on my first trip abroad to the land of the Great Wall. I ate my way through the country, moving from city to village, absorbing the many nuances of traditional Chinese cuisine. I remember digging into a bowl of braised prawns Sichuan style at a restaurant in Chengdu. It was generously sprinkled with Sichuan peppercorn and dry red chilli and I couldnt take a bite without having a swig of beer, which I held tightly in my other hand. My young interpreter was most amused with my determination to go through this punishment. I can still remember the name of the street the restaurant was on. It was called Street of the Ghost and it was so named because it served food until the ghostly hours of the night. There were many more such unforgettable experiences.

When I returned, I promised myself I would someday start a new kind of Chinese restaurant in the country, one that would give Indians a chance to taste authentic Chinese. At the restaurant I also wanted to experiment with the cuisine and adapt it for India. Crackling spinach, one of our signature dishes, is, for instance, a variation on the well-known Chinese dish crackling seaweed that is not easily accessible in India. The book reflects this approach, giving you a sense of the varied riches of Chinese cuisine and also teaching you how to cook Mainland Chinas signature dishes. I hope you enjoy it.

Anjan Chatterjee, February 2010

Chinese Regional Cuisine

Chinese cuisine can be broadly divided into four main schools or styles of cookingPeking, Shanghai, Sichuan, and Guangzhou (Canton). Here is a quick introduction to them.

Peking (Northern School)

Besides the local cooking of Hebei (the province in which Peking is situated), Peking cuisine embraces the cooking styles of Shandong, Henan and Shanxi, as well as the Chinese Muslim cooking of Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang. Also, being the capital of China for many centuries, it has become its culinary centre, drawing inspiration from all the different regional styles. During the winter, farmers from various regions of China would come down to Beijing and display their food on carts in main streets. The cuisine of Peking has been much influenced by these migrant cooks. However, Peking food is essentially the imperial banquet cuisine where duck, piglets, and venison are served whole on platters with elaborate garnish. Use of expensive and rare ingredients such as crab roe, quails eggs, lobster tail, and baby turtle also form an integral part of this style.

Next page