Acknowledgements

T his book would not have come about without the hospitality and generosity of my friends and relatives in Italy. They opened their homes, their hearts and their kitchens to me, and I will be forever grateful. Thanks go to the following and their families: Zio Alberto, Zia Rosaria, Maria Chiara, Mattia and Silvana, Domenichella, Giacinto and Madalena, Dora, Antonio and Rosalba, Nicola and Nicoletta, Antonietta and Gino, Biasetto and Giuseppina, Tiziana and Alberto, and last but not least, Enza.

It was a big move to leave the comfort of my home and the income of my work to run away to Italy for a year. Thank you to my brothers, who had to hold the fort and fill the gap that an only daughter leaves. My family has been a constant source of encouragement and support through this whole process. Thanks to my mother Joan Di Sciascio for proofing every version of the manuscript, overseeing and approving the content on behalf of my father, and giving me confidence to write. Thank you to Peter Di Sciascio, who has been a most eager fellow traveller on my journey to becoming an author.

Thank you also to the many people who have helped in the publishing of this book. Janet Jenkin was the first person to read and provide initial edits on my earliest draft. Janet was a keen test cook, along with a host of friends who provided invaluable feedback on the recipes. I must also thank Silvino Di Biase for providing detailed descriptions of his youth with my father and their migration journey, and Maria Chiara Di Sciascio for being my long-distance fact and dialect checker. Thanks must also go to Jacqui Gray, who championed my manuscript, Foong Ling Kong for enticing me with her enthusiasm and the team at MUP who helped make my words shine.

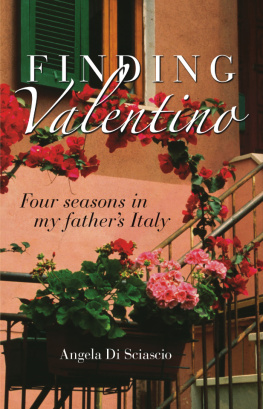

But most importantly, I must thank my father Valentino Di Sciascio. His story, his life and his character have driven this book. His disease has rendered him unable even to comprehend that this book exists, and I have been forever conscious of the responsibility I hold in publishing this book: to respect his ethnicity, his siblings, his village, his privacy and his memories. I hope I have done justice to him and his story.

1

Cobblestone roads, il Papa and pepper

T he first person I encounter when I arrive in Italy is not my friendly and helpful cousin, Giacinto. It is Fangio. He doesnt introduce himself as Fangio but I soon discover his goal in life is to be Fangio. After a 28-hour journey, having survived turbulence and delays, avoided terrorist attacks and sat in airline seats designed for smaller bottoms than my own, I find myself a passenger from the airport to my hotel in the hands of Fangio. At speeds that draw my cheeks back off my face he weaves his way down freeways, busy roads and side streets to get me to Trastevere, the neighbourhood in which I have chosen to immerse myself for my week in Rome before heading to my fathers village. We screech to a halt and as he deposits my luggage on the road he holds out his hand for a tip. Whether it is out of sheer relief to have my life out of his hands, the joy of starting my adventure or jetlag, I hand over far too many euros. He speeds off. Welcome to Rome.

I am dizzy at the thought of what lies ahead of mea year with my relatives, travelling, studying Italian and immersing myself in the country and culture of Italy. I am here to live, breathe and feel Italy with all my senses. This is not my first time overseas. I have travelled a lot, lived in foreign countries for extended periods and been away from my family. But theres something different about this trip. No longer a young twenty-something in search of adventure, Im older now, my parents are ageing and I view the world differently. I have come to realise just how precious it is to have a close, strong family around you, and how fragile.

Trastevere is everything I want it to be, a real Roman neighbourhood with a maze of tiny cobblestone streets that wind their way from A to B with everything in between. Here are streets with washing hanging out the windows, mammas calling to their children playing in the piazza below, a furniture restorer next to a blacksmith next to a bakery next to a tobacchi . Each day at midday I see women queuing for meat at the spotlessly clean butchers. I have never seen such pale veal. There are cheese shops with fresh ricotta in the window to entice you in; once inside, you are hit by both the aroma and the sheer variety of fresh produce on display. Busy fruit and vegetable stalls are stocked with deep-orange mandarins from Sicily, still bearing their tufts of green leaves, glistening bulbs of crisp fennel, globe artichokes plucked of their outer leaves and trimmed carefully by the shopkeeper and ready to cook, and yellow broccoli looking like a crown you can imagine the King of Thailand wearing. Everything is fresh daily. The way shopping is meant to be.

I long for a coffee but wait days until I get up the courage to actually enter a bar and order one. Ordering, drinking and partaking in coffee is such a serious ritual here that I am nervous of exposing myself as a fraud, an Italian who cant even order a coffee. Several times I stand at the door of a bar, willing myself to be brave and enter. Finally on the fifth morning I walk confidently in, order an espresso and cornetto from the uniformed cashier, take my receipt and stand at the bar. This first coffee, nervously sipped, surrounded by Italians on their way to work, is the best I have ever had.

Such a coffee is a normal breakfast for Italians. Their main meal is taken at lunch and usually involves several courses including antipasto , a collection of cured meats, preserved vegetables or crostini (dried breads topped with spreads or roasted vegetables); a first course, or primo , of pasta, soup or rice; and a main meal, called the secondo , of either meat or fish accompanied by a contorno , usually seasonal vegetables or salad. This is followed by dolce , a fruit or sweet dish and to finish, espresso. While this sounds like a lot of food, dinner is traditionally much lighter than lunch and Italians dont tend to snack between meals like we do. Meal times are a chance to savour and enjoy the food of the season and to spend time with family and friends. And I plan on making the most of every opportunity to do just that.

With this in mind I hunt out restaurants serving local fare to local people. I am surrounded by pizzerie and trattorie , some small and basic, some large and catering for the tourists. The latter I avoid.

Tucked in the corner of the tiny Piazza de Renzi in Trastevere, the small, family-run Trattoria Da Augusto typifies the dining experience I hope to find all over Italy. The furniture is basic, with tables covered in white paper and customers crammed in intimately. People call out Buon giorno in a familiar way as they enter and the kitchen staff responds in chorus. I watch with delight. There are no menus so the waiter slowly lists the dishes for the day. I choose stracciatelli soup, braised rabbit, broccoli and some red wine, while the waiter simply listens attentively. Waiters in Italy take their role seriously; I never once see one write an order down. What follows is glorious: silky egg soup, a Roman staple that warms my soul, delicate rabbit that falls off the bone and broccoli cooked to perfection and drizzled in olive oil. At the end of the meal, the waiter calculates my bill using his pen on the tableclothfourteen euros. I am in heaven.