The editor and publisher are grateful to the following for permission to use material in this book: Little Brown and Company for excerpts from Down the Nile Alone in a Fishermans Skiff by Rosemary Mahoney; the family of Bettina Selby for excerpts from her Riding the Desert Trail by Bicycle to the Source of the Nile. Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders. We apologize to and thank any authors or copyright holders who we have not been able to properly acknowledge. If a work in copyright has been inadvertently included, the copyright holder should contact the publisher.

All the illustrations in this book are from The Nile Boat, or Glimpses of the Land of Egypt by W.H. Bartlett (London: Arthur Hall, Virtue, and Co., 2nd ed., 1850). Reproduced courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library, the American University in Cairo.

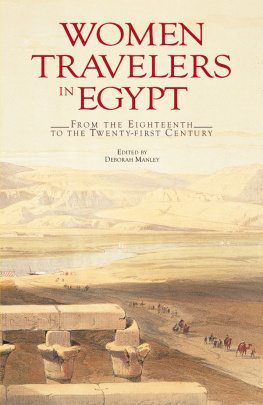

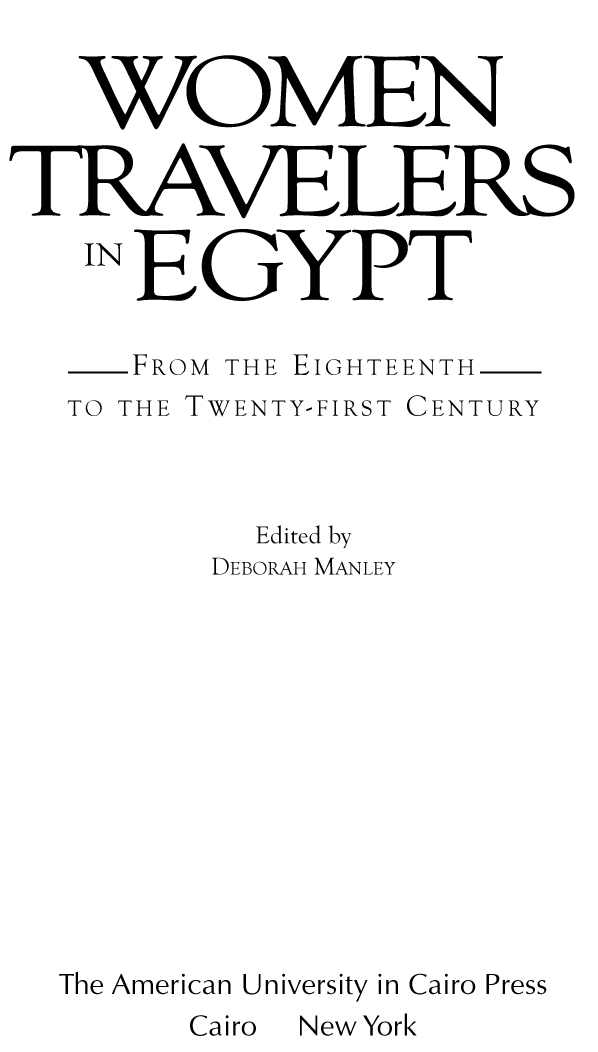

First published in 2012 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2012 by Deborah Manley

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Dar el Kutub No. 24572/11

eISBN: 978-1-6179-7360-4

Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Manley, Deborah

Women Travelers in Egypt: From the Eighteenth to the Twenty-first Century/ Deborah Manley. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2012

p. cm.

ISBN 978 977 416 485 9

Women TravelersEgypt

I. Title

910.92

1 2 3 4 16 15 14 13 12

Designed by Jon W Stoy

Lady Tobin, traveling through Egypt with her husband in 1853, wrote about keeping a journalthe record upon which her account of her journey would depend:

I quite agree with Miss Martineau that one of the greatest nuisances in travelling is keeping a journal. One is far more disposed to lie down and rest after a fatiguing ride of eight or nine hours on a camel, beneath a burning sun; thanhaving made a hasty toiletteto take out ones writing materials. I persevered, however, and rejoice that I did so.

We can rejoice also for it was upon such journals that travelers wrote the books which we can still read, enjoyand learn fromtoday. In this book the accounts are linked together by the journey rather than time. Thus, a traveler in, say, 1824 may stand side by side with a traveler in the late twentieth century and share their response to Egypt.

Most men set out to travel with a purposefor many their purpose was, and is, related to work rather than leisure. In the past women needed a purpose to justify their travels more than did menfor, unless they had enough money of their own, they had to ask for either male or female permission. Some women travelers were invited to make up numbers in a group or to accompany their husbands, but then quite often wrote a book of their travelsand thus became the traveler still remembered, while the men of their party are remembered only as a presence. Eliza Fay, Anne Katherine Elwood, Harriet Martineau, Amelia Edwards, M.L.M. Carey, and others in this collection were such travelers.

As we wander through the writings on travel in Egypt, we see both how different and how similar mens and womens accounts can be. When we read a mans account, the author is usually the hero and any accompanying ladies are backdrop only. In the womens accounts the Egyptian crew often come forward to front of stage. The dragoman (or tour leader and guide) usually moves to prime position, arranging everything for the whole party.

Early European travelers in Egypt, such as Danish Captain Frederik Norden, in 1737, were explorers rather than travelers or tourists, but even then a lady was a member of the party. Some of the earlier women travelers, such as Eliza Fay or Sarah Lushington, were passing through Egyptwith their husbandsen route for India or returning from the East, rather than taking the long, long route around the Cape of Good Hope. But it was they who wrote the accounts of their journeysoften offering useful advice to future lady travelers. In 1836 the wealthy American couple, the Haights, traveled very widely in the Old World, and were among the first American tourists on the Nile. Again it was Mrs. Haight who wrote of their journeying.

By the mid-nineteenth century some women were traveling far and wide in their own rightand sometimes on their own. Two who came to Egypt were from Central Europe: the Viennese widow Ida Pfeiffer in the early 1840s, and the German countess Hahn Hahn a few years later, both traveling first to Syria, as the whole of the eastern Mediterranean lands were then called, to visit the Holy Land, then onward to Egypt and up the Nile. By mid-century the political economist Harriet Martineau traveled with a small group first through Egypt and then to Sinai and Petra. But even at that time the main guide book to the country, Murrays Guide, gave no advice to women travelers on the clothes they might need or the items they would be wise to bring. Some of them, like Mrs. Carey in 1861, brought her maid to look after her needs, but also gave good advice on what to bring. Others, including Martineau, attended to their own washing and ironing. All depended on the local guides to oversee their needsthis was particularly true of travelers like Isabella Bird when she traveled through the Sinai Peninsula, and was cared for with great tenderness by her Bedouin guides when she fell ill.

Perhaps the woman traveler who had the most long-term impact both on Egypt and on travel to Egypt was Amelia Edwards. She came almost by chance, having been disappointed by the weather in southern Europe in 1873, but she was so dismayed by the way the ancient treasures of Egypt were being ransacked by travelers and Egyptians alike that, on her return to England, she worked to set up the Egypt Exploration Society to organize digs in a legal and orderly manner, and she funded the first Professorship of Egyptology in Britain.

By the latter half of the nineteenth centuryand the coming of Thomas Cook and his Nile steamersmost travelers to Egyptsuch as Norma Lorimer in 19071908had become tourists, seeing Egypt from a big, highly organized ship, much as most tourists do today. Yet even now there are a few travelers who, like Bettina Selby and Rosemary Mahoney, at the end of the twentieth century, went to Egypt with almost as much sense of adventure as the earlier travelers.

One of the great differences between the female and male travelers was that the women could meet the women of Egypt. Some of the women started as travelers but then lived in Egypt for several years, and would have spoken Arabic and thus have had further insights into Egyptian life. Sarah Belzoni came with her husband but spent much time independent from him. Mary Whately, teacher and missionary in Egypt from the 1870s, met both the poorest women along the Nile and the richest women in the harems of Cairo. Ellen Chennells was employed by the Egyptian royal family to educate the harem. Sophia Poole, sister of the famous Edward Lane, lived among the women of Cairo for many yearsand became an object of other travelers interest in her own right. And the women travelers were able to observe, meet, and converse with local women more than the men could.

Next page