By the same author

Frontiers of the Caribbean

(Manchester University Press, 2017)

Canouan Suite and Other Pieces

(Papillote Press, 2016)

Island Voices from St Christopher and the Barracudas

(Papillote Press, 2014)

For jazz historian Val Wilmer, a good friend

In memory of Erik Bye (1926-2004)

and Coleridge Goode (1914-2015)

First published by Papillote Press 2021 in Great Britain

Philip Nanton 2021

The moral right of Philip Nanton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designer and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CRO 4YY

Book design by Andy Dark

Typeset in Minion

ISBN: 978-1-9997768-9-3

ePub ISBN: 978-1-8380415-1-9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Papillote Press

23 Rozel Road

London SW4 0EY

United Kingdom.

And Trafalgar, Dominica

www.papillotepress.co.uk

CONTENTS

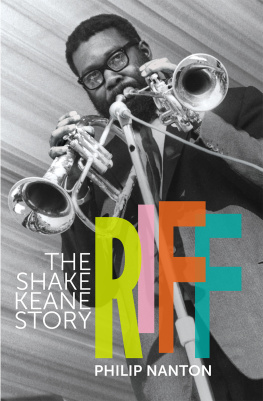

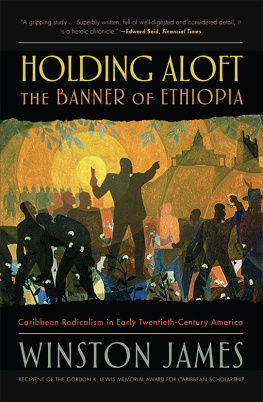

Cover photo: Shake Keane playing trumpet and flugelhorn, National Jazz Festival, Richmond, Surrey, 1963. ( Val Wilmer )

Shake Keane, The Angel Horn: Shake Keane Collected Poems (St Maarten: House of Nehesi, 2005), 178. Henceforth Collected Poems .

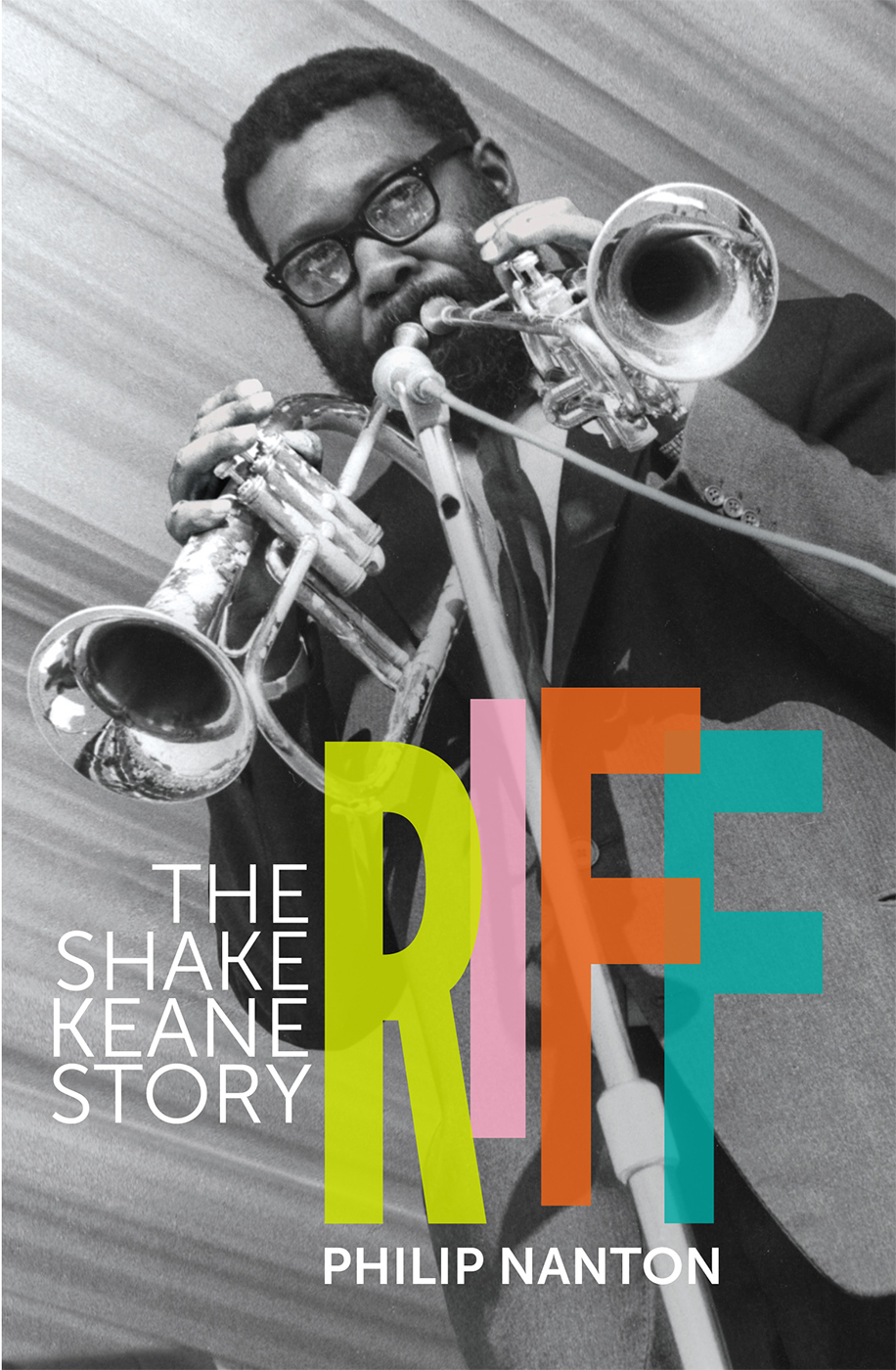

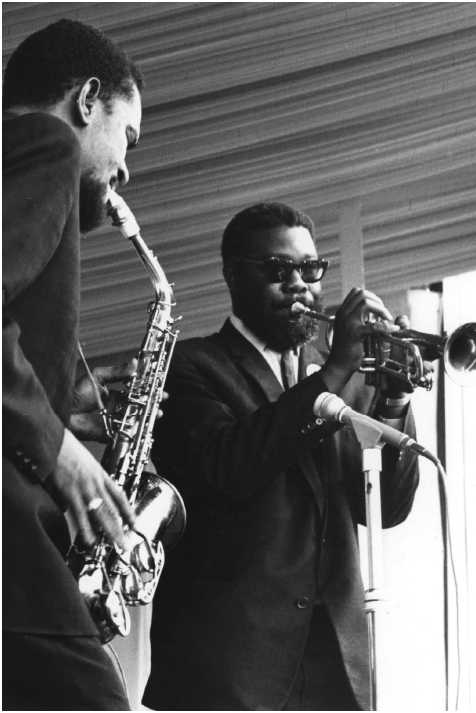

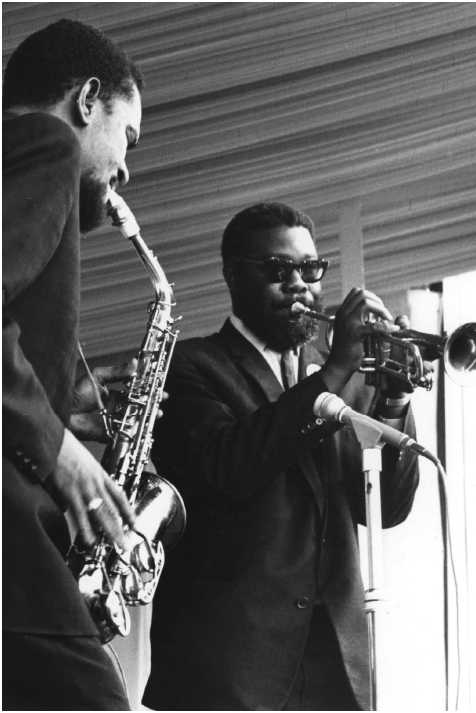

Joe Harriott (left) and Shake Keane, National Jazz Festival, Richmond, Surrey, 1963. ( Val Wilmer )

RIFF

Shake Keane was back home in St Vincent working as a teacher when I first met him in 1979. In his lunch hour, we would occasionally retreat to the quiet of Vees Snackette, a tiny bar on the corner of busy Bay and James Street in the islands capital, Kingstown. The bar, surrounded by shops and government offices, was close to the school where Shake was then teaching. (The entire corner block is now a bright but ugly KFC franchise.) Vees had only two windows, one looking out onto each congested street. Smaller than a one-car garage, the bar was a simple room with a garish melamine-coated counter and three high wooden stools. We were the only customers. Miss Vee, a sturdy, no-nonsense lady, would put out a petit-quart bottle of rum and a small bowl of ice for me. Shakes lunch comprised three bottles of Guinness. She would then leave us alone as she scurried around in a back room.

We exchanged returnee gossip about life in England of the 1960s and the effect of coming back to St Vincent. By this time Shake was sceptical about his return. He had abandoned his flourishing jazz career in Europe and lost out to political manoeuvring in St Vincent over the post he had most wanted and had returned to implement Director of Culture for St Vincent and the Grenadines. Sacked from this job after two years and with no other source of income, he felt compelled to accept the first vacant post and became Principal of Bishops College, a grand name for a small secondary school in Georgetown, the islands second town in the northern Windward district. It seems that even in the relative tranquillity of teaching disaster lurked. At one of our meetings he described almost losing his life when one evening, during his time as Principal, he went to turn on an electric lamp and was hurled across his office. Faulty wiring.

Shake was by then in his early fifties; tall and broad, around six foot four and somewhat shaggy in appearance. His size was emphasised by his characteristic loose-fitting clothing above brown latticed leather sandals. By this time he had a luxuriant grey beard and a thinning head of hair. He moved slowly when the pain of gout struck. A large pair of spectacles rested on his nose below heavy grey eyebrows. Between his long delicate fingers he invariably held a roll-up cigarette. He spoke in a deep baritone voice. This apparently fierce demeanour was softened in conversation by an unassuming smile that came quick and easily.

Vees Snackette looked directly onto the street. Passersby would see him there and hail the famous musician and returned fellow Vincentian. A celebrated figure in the island, he was used to this public show of interest and would often be stopped in the street. A brief chat was a public sign of connection to a man of international stardom. One lunchtime, a young stevedore, hot and sweaty from the nearby docks, entered the bar:

Mista Car-heen! Mista Car-heen! Cuse me sar. Ah have one sar. Dont mind the clothes all ragga, sar. I just off the jetty. You could hear me sar? Dis one goin be good sar. It go so

I was liming on the block

wid de boys from de rum shop

is then I bounce up big Mary

them days she frennin Big Nancy

OK, OK, pal, enough.

It have plenty more verses sar. You like how it going? You could help me fix it up sweet, sweet? Put a lil chorus. Get recording contract and ting. Or even a lil drink, den sar? Me troat dry.

Shake bought him the drink.

Supplicants came in other forms. At one of our meetings I myself showed up with a poem that Id written. Without hesitation he took out a pen and began deleting words and rearranging its lines, circling sections with arrows going first in one direction then another to different parts of the page, instinctively aiming at bringing the page alive. I like to think I learned something about poetry firsthand from Shake.

At this stage of his life he had been back in St Vincent for six years, after more than 21 years away, first in London then in Germany. Other locations, especially New York and Norway, were to follow. These movements suggest an itinerant a wanderer who was both framed and influenced by the twentieth century, his lifespan stretching from 1927 to 1997. Indeed, he absorbed and was absorbed by many of the currents flowing through the century. In his chosen fields, especially jazz and poetry, he not only understood them but knew how to excel in them.

Three twentieth-century currents were important in shaping his individual talents and personality. The first of these was the rise of nationalism in the Caribbean. Shake grew up and lived through a time when regional and island national sentiments were at their strongest expressed in demands for self-government, the rise and fall of regional federation and, finally, the achievement of island-based political independence. This nationalist current was also flowing around the world, touching the colonies from the Caribbean to Africa and Asia. It brought with it political change and a sense of the importance of nation-making which no thinker of the twentieth-century Caribbean could ignore. But when Shake departed St Vincent for England in 1952, the island was still a colonial outpost; only one year earlier it had experienced its first general election under adult suffrage. When he returned in 1973, it was a few years after the island had attained Associated Statehood with Britain (1969). This was, in effect, when locally elected politicians gained control of the islands resources and budget, taking over from the British. Six years after his return, St Vincent gained full political independence. If, as a young man, Shake had left a colony, he returned to a place in which local people vied for influence and power and local party politics was ruthless. He returned, therefore, to a different island from the one he had left.