PENGUIN BOOKS

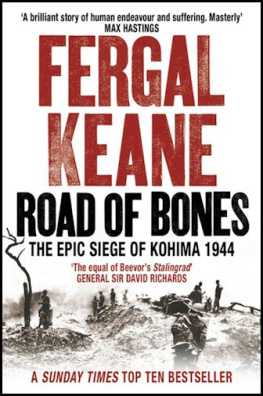

SEASON OF BLOOD

Fergal Keane OBE is one of the BBC's most distinguished correspondents, having worked for the corporation in Northern Ireland, South Africa, Asia and the Balkans. He has been awarded a BAFTA and has been named reporter of the year on television and radio, winning honours from the Royal Television Society and the Sony Radio Awards. He has also been named Reporter of the Year in the Amnesty International Press Awards and won the James Cameron Prize and the Edward R. Murrow Award from the US Overseas Press Association. His other books include The Bondage of Fear, Letters Home, Letter to Daniel and A Stranger's Eye. Season of Blood won the 1995 Orwell Prize.

Fergal Keane was born in London and educated in Ireland, where he keeps a small cottage on the south-east coast.

Fergal Keane

SEASON OF BLOOD

A RWANDAN JOURNEY

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by Viking 1995

Published in Penguin Books 1996

Copyright Fergal Keane, 1995

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The acknowledgements on constitute an extension of this copyright page

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192773-2

Dedicated to the memory of the people of

Nyarubuye parish, murdered, April 1994

When evil-doing comes like falling rain, nobody calls out, stop!

When crimes begin to pile up they become invisible.

When sufferings become unendurable the cries are no longer heard. The cries, too, fall like rain in summer.

BERTOLT BRECHT

The grave is only half full. Who will help us fill it?

RADIO MILLE COLLINES , Rwanda, April 1994

Contents

Acknowledgements

I found this a difficult book to write and am indebted to several people whose kindness and advice helped to make the task easier. First and foremost a thank-you to my wife, Anne, whose support and understanding was my mainstay. While the book is my own story, the Rwandan journey was, of course, a team effort. I am for ever grateful to my colleagues and travelling partners David Harrison, Glenn Middleton, Rizu Hamid and Hamilton Wende. They were good friends and total professionals. My thanks also to Chris Wyld at the BBC for suggesting that I go to Rwanda. Also to Vin Ray, Chris Cramer, Glenwyn Benson and Tim Gardam.

At the Panorama office in London, Lucy Crowe, Jim Baker, Faith Nyindeba and Ali Yusuf Mugenzi worked against the odds to ensure that our film on the genocide was edited and broadcast in record time. Thank you to Julia Bourhill in Johannesburg for making the all important travel arrangements.

I am also deeply grateful for the advice and information provided by African Rights, whose report on the Rwandan genocide is the most comprehensive account yet written. It provided invaluable source material on the roots of the genocide. Also to Mdecins Sans Frontires, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, who have produced informative and insightful reports. In Rwanda, Lt Frank Ndore, information officer of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), was open-minded and helpful, and never sought to interfere with our journalistic freedom. Major Guy Plante of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) did his utmost to provide help and information.

Mark Doyle of the BBC and Aidan Hartley of Reuters were always kind and helpful in Kigali, my thanks to them both. Among other journalists whose work proved an inspiration were Chris McGreal of the Guardian, Mark Huband of the Observer, Sam Kiley of The Times and Robert Bloch of the Independent. My friend Eric Ransdell, of US News and World Report Magazine, provided vital advice on the do's and don'ts of reporting in Rwanda. To Tony Lacey and Donna Poppy at Viking, the usual, eternal thanks for wise advice and patience. Similar thanks to my agent Gill Coleridge, whose timely faxes ensured I finished the book.

My greatest debt, however, is to the survivors of the genocide. They gave me their time and their stories, and I am humbled by the recollection of their quiet dignity in the face of appalling suffering. I will never forget them.

Grateful acknowledgement is made for permission to reproduce extracts from the following copyright works: to Reed Consumer Books for Poems 19131956 by Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Willett, published by Methuen London; to African Rights for Rwanda: Death, Despair and Defiance, published by African Rights; to A. P. Watt Ltd on behalf of Michael Yeats for A Prayer for My Daughter by W. B. Yeats, first published in Poetry in November 1919, and included in Michael Robartes and the Dancer in 1921.

PROLOGUE

Bloodlines

I do not know what dreams ask of us, what they come to collect. But they have come again and again recently, and I have no answers. I thought that after the bad nights of last summer the dead had abandoned me, had mouldered into memory. But the brothers and sisters, the mothers and fathers and children, all the great wailing families of the night are back, holding fast with their withering hands, demanding my attention. Understand first that I do not want your sympathy. The dreams are part of the baggage on this journey. I understood that from the outset. After all, four years in the South African townships had shown me something of the dark side, and I made the choice to go to Rwanda. Nobody forced or pressurized me. So when I tell you about the nights of dread, understand that they are only part of the big picture, the first step backward into the story of a journey that happened a year ago. So much for explanations.

Let me tell you about the dream that comes back again and again, the big bad one, as I have started to call it. I am asleep and become aware of hands creeping up and down my body. They prod and probe until I am awake, and in a startled moment I realize that I am lying at the bottom of a pile of rotting corpses. But they are moving, like a mound of eels at the fishmarket, or like snakes, things that slip and slither. I am being passed up through the layers of the moving dead. That is why the hands are touching me, pulling and pushing me up to the top. But I do not want to go to the top. Because up there is a man with a machete. He is looking for me. He has spent all day looking for me and is sure that I am hiding in the pile of bodies. The corpses are intent on betraying me and I am paralysed with fear. There is nothing I can do; I am helplessly pushed up through the smell of the dead towards the sunlight, where a man is waiting to kill me. I thought I had survived. I thought I had made it through, that the killers had passed me by and gone on to another village. But Christ forgive the dead, they have called the knifeman back. One of us still lives, they cry. One of us still lives. And now, any second now, I am going to be delivered to the top of the pile, where a man with bloody eyes and beer on his breath will sweep me away. If I am lucky the blow will cut my skull in two, massive brain damage, instant death. If not, I will linger, moaning and gasping with thirst, breathing the last rotten breaths of life until death comes as a sweet mercy. As I am about to be handed up, I wake out of the dream, bolt upright, feeling the pillow wet, my t-shirt sodden, and the darkness close and warm.

Next page