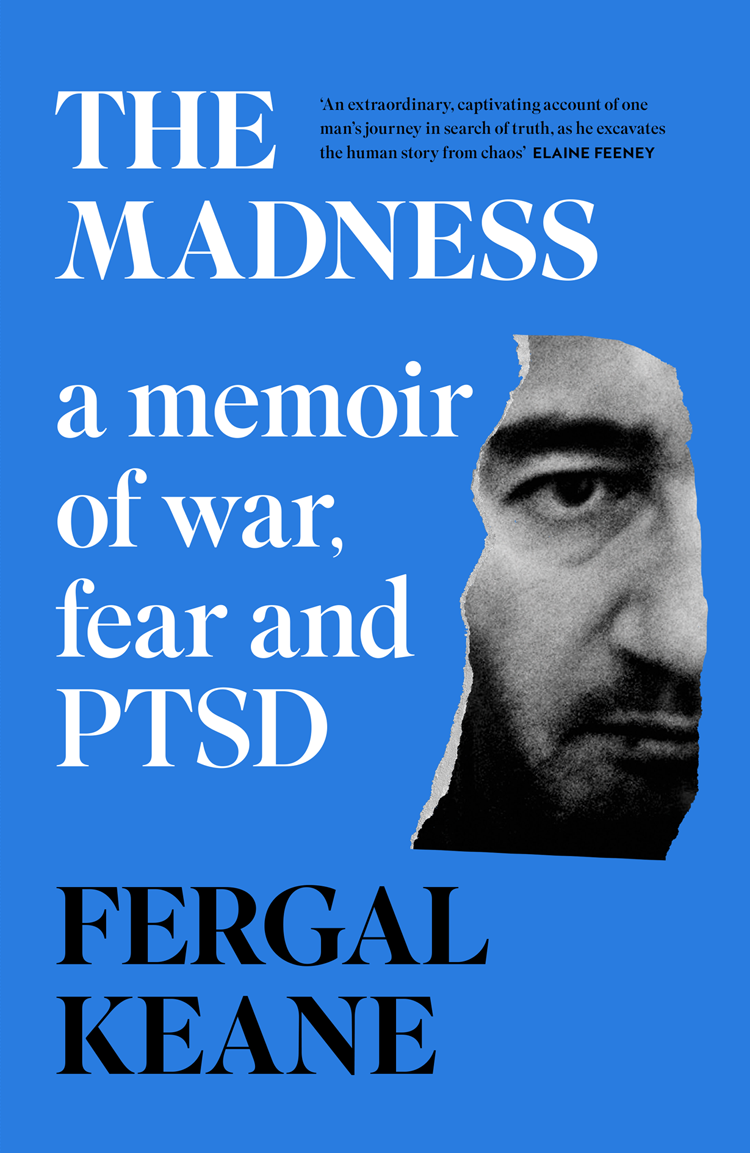

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

Copyright Fergal Keane 2022

Cover photograph courtesy of the author

Fergal Keane asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008420420

Ebook Edition October 2022 ISBN: 9780008420444

Version: 2022-09-22

For Alice

Prologue

Kyiv, 20 February 2022

I open the curtains and see the light coming up. It will be a beautiful day. There is no cloud. The temperature has risen above zero. Crisp, dry weather with little wind to chill our uncovered faces. A day to walk down Khreshchatyk street and eat in the Turkish restaurant with the view up towards Maidan Square. We sat there last week and saw the demonstrators materialise outside, a long line of them everyone from far-right nationalists to the local LGBTQ organisations. Only in this part of eastern Europe, this Kyiv, would you see the likes of it. Together, they sang the national anthem Glory to Ukraine and then dispersed.

But what is coming? What is coming from across the horizon towards Kyiv, Dnipro, Kramatorsk, Mariupol, Odesa, and all the land that lies in the way of Putins malign designs?

We have exhausted ourselves with speculation. Every meal is a repeat of the same conversation. The Russia experts among our group think it unlikely that Putin will invade. Or at the worst they think hell escalate in the east but not try to take Kyiv. There is constant questioning of Allied intelligence which has been warning daily of the invasion threat. How do they really know he is going to attack? My gut says he will not leave this job unfinished and allow a rebellious government to remain in Kyiv. But I waver briefly when the Russians announce they want to de-escalate.

Not for long. Day after day, the armies gather on the border. Pontoon bridges appear. Soon the provocations start in the east. I watch it unfold and think of my friends in the way of the advance. Anatoly and Svetlana, the dear elderly beekeeper and his family who have suffered so much already, live in the path of the Russian army.

Still, see how lovely the light is, the pink glow spreading up the sky from the east. The Russians concealed in the forest see the same dawn. They will be restless. Most soldiers on the eve of battle think of loved ones and home. Or they do their best not to think of what might be lost forever in the days and weeks to come. None know for sure that they wont end up dead or with their guts spilling out, or with some other particularity or combination of anatomical dismemberment, in a muddy field or ruined house.

The Ukrainians facing them see the same light. The people of Bucha and Hostomel and Irpin are heading out to work, or taking their kids to school. I have driven through these places on the way to and from meetings; they are not yet weighted with any significance, just names of places I pass by.

It is five days since I walked in no-mans-land with Major Sergiy Khomenko, who grew up in a border village, whose father was a soldier in Soviet times, and who said he would stand and fight if the Russians came. But nearly every soldier Ive ever met said that. Would it be different for him if the columns come rolling down the road, all heavy calibre bullets and rockets, all that insane noise of an army attacking? We were standing near the forest on the border with Belarus, deep snowbound forests that might conceal an army that probably did: watching us and waiting for its orders to advance. That was a week ago, when I still thought there was a chance, a very small one, that diplomacy might work. But Putin is playing a game and the shrewder of the world leaders know it. His army is coming.

I struggle with myself. To stay or leave? I have made promises: to those I love. To myself. No more front-line war reporting. I also fear my nerves might not be able to take it. Am I asking for another crack-up and hospitalisation? I have said to myself often in the last few years that I cannot endure another breakdown.

But the surge of desire to stay here is so strong. Its in my head, and in the marrow of my bones. The reasons are pouring out. Im a reporter, Im meant for this. History is about to happen, how can I leave this? I feel the adrenaline pulsing. Going to bed at night part of me wishes to be awoken by explosions so the decision will be taken out of my hands: Kyiv cut off, me unable to leave. Nothing for it but to knuckle down and report the battle for the city. My conscience knows this is an addicts evasion. I watch the sun set on another day without war. I will make my decision soon. Or it will be made for me.

I have been afraid all of my life. Dread still wakes me in the night. It is there to greet me in the morning. It comes at differing velocities. It can be an anxiety that nags all day without a name, or I can be driving down an Irish country road, the sea blue and dreaming on my left, and I have to pull over and sit shaking, hands clasped tight under my armpits, visions of catastrophe swirling in my head, the urge to vomit building, while I struggle to form the words of the Serenity Prayer. A muttering man, dry heaving by the roadside in his late middle age, a sight for no eyes.

God grant me the serenity

To accept the things I cannot change

The courage to change the things I can

And the wisdom to know the difference.

I have been diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition arising from exposure to multiple instances of trauma, experienced over a long period. It is regarded as significantly harder to treat than a single traumatic episode. My first PTSD diagnosis was twelve years ago. Since then I have attended numerous sessions of therapy. I have taken courses of anti-depressants, which made me emotionally numb, and physically constipated, but which also prevented me from reaching a stage of desperation where I might harm myself. Despite this, and countless promises to do otherwise, I have gone back to the wars, again and again.

I am also a recovering alcoholic and have been sober for more than twenty years. The bottle was my medication of choice during many of the years I went to the wars. The struggle with alcohol described in this book is an integral part of my attempts, and those of many I know, to escape the pain of PTSD by getting out of it, a description of drunkenness that is as accurate a psychological representation of my experience as Ive ever read. Out of the pain is where I wanted to be. The consequences of that desire would be unremittingly counterproductive.

Back in January 2019 I declared that I was leaving front-line reporting because of the disorder. The decision was prompted by a nervous collapse the previous summer after a reporting assignment in Sudan. There were expressions of support from the public and other journalists. Under the headline We should thank Fergal Keane for bearing witness to unbearable horrors, Suzanne Moore wrote: It was tremendously brave, even for a brave man such as the BBC reporter Fergal Keane to talk about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.