Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Preface

I could have begun this book in 1981, but instead I decided to have children. The trade-off is not what you might imagine. At the time, the personal message was clearer than the professional one. I was interviewing people with cancer about the aspects of their lives that had helped them cope with their illness and the debilitating treatments it imposed. One especially articulate woman led me to change the course of my life. She and her husband had raised four children who were now, as she put it, her sustenance through the long months of radiation and chemotherapy. I have rarely met anyone so satisfied with the life choices she had made. I returned home and said to my husband, I think were making a mistake.

Until that moment, we had decided to remain childless, so we could devote ourselves to our admittedly exciting careers. During the more than ten years that we held to this resolve, I published a lot of scientific papers, and he designed a lot of buildings. We continued our work after the children came, of course, but our lives now seemed to be linked backward and forward in time to our ancestors and to future generations, and outward, to our community, its schools, and our neighborhood, in ways that we had never before experienced. The sustaining relationships I had been writing about in my papers were now a more immediate part of my life.

Over the years, my scientific interests broadened from a social-psychological focus to include a biological perspective: first, as an interest in healthwho stays well, who gets sick?and then further back to the underlying neuroendocrine processes that get a person from good health to bad or from bad health to well again. I began to see how the social and biological pieces of a human life fall into place, complementing, influencing, and sometimes disturbing one another.

Like many people, I originally assumed that biology largely determines behavior, and so it was a tantalizing surprise to see how clearly social relationships forge our underlying biology, even at the level of gene expression. Chief among these social forces are the ways in which people take care of one another and tend to one anothers needs. An early warm and nurturant relationship, such as mothers often enjoy with their children, is as vital to development as calcium is to bones. Even in adult relationships, we tend to each others needs in ways that sustain long and healthy lives. My story, then, is about giving carenot the necessity or obligation of caregiving, but its potency.

My story is also about women and men and the differences between them. It did not set out to be so, but this has become an insistent theme in ways that are surprising and perhaps controversial. Women play a more central role in tending to others than do men. Tending abilities are, by no means, unique to women, but when we tell the story of man from the perspective of woman, we necessarily see different thingsless about power and aggression, more about caring and nurturance, and, perhaps most surprising, a fair amount about how caring and nurturance shape the expression of power and aggression.

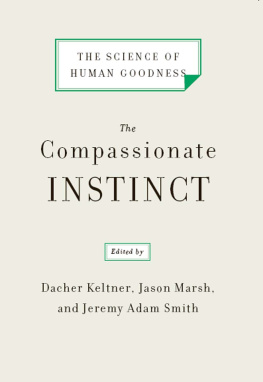

This view is somewhat at odds with the prevailing account traditionally offered by sociobiologists or evolutionary psychologists. Writers from these traditions often represent the human social landscape as a battleground, where the successful outmaneuver the weak through a competitive edge, deception, or sheer blunt force. Even relations between the sexes are said to be a battle. I find this characterization to be a baffling half-truth at best. It leaves out so much of human naturehow we love, nurture, and care for one another in manifold ways.

My own fieldthe study of stressalso reflects these competing viewpoints. The dominant metaphor, fight or flight, represents the threatening social landscape as a solitary kill-or-be-killed world. My work suggests instead that the human response to stress is characterized at least as much by tending to and befriending others, a pattern that is especially true of women.

When I first challenged the idea that fight or flight is a universal characterization of stress, I was concerned about how it might be received. The response was very gratifying. I received letters and e-mails from all over the world, many of which posed questions, others of which expressed appreciation. But most of them had a common theme, which is reflected in the comments of one woman who wrote, Ive been reading popular accounts of science for years, and finally, here is something I recognize. This is one of my goals in this book, namely to add balance to our view of human nature. After some debate, I decided to call this book The Tending Instinct, because I want you to recognize that the care-giving we provide to others is as fundamental to human nature as our selfishness or aggression, themes on which scientists more commonly, though perhaps overzealously, reflect.

Instinct is a loaded word, and I choose it with cautious deliberation. Some scientific accounts will claim that, to be instinctive, a behavior must be automatic and invariant, destined to emerge, regardless of the environment in which it will be expressed. But, in fact, environmental conditionsintense stress, for examplecan upset, derail, and change the form of much biologically driven behavior, and this is true of tending as well. Tending is not invariant or inevitable, but it is insistent in ways that justify the term instinct. We have neurocircuitries for tending as surely as we have biological circuitry for obtaining food and reproducing ourselves. Brain development has been driven by our tending, as well see. And how others fare in times of stressfrom how calm they are to their likelihood of becoming illdepends on the quality of the tending they receive.

But instinct is a loaded word for reasons that have political significance as well. When instinct is combined with the idea of tending, especially in women, it is a slippery slope to mothering instinct, womens destiny, and other terms that have so often been used to box women into roles they may not choose to play. In the years that I trained as a scientist, we solved this political dilemma by arguing that men and women were the same. Cultural and social expectations led us to assume different roles, of course, but if we could magically eliminate these sources of influence, the mythology went, our natures would be human, not distinctively male or female. How did we sustain such a fiction during the decades of research attesting to the contrary? That is a rhetorical question I will not attempt to answer. But probably the saddest fallout of our efforts to squeeze men and women into the same psychological mold was our intense embarrassment over anything inconveniently female in nature, and this included motherhood.

So squeamish have we been about the role of mothers that weve often sidelined and marginalized it, referring delicately to the caregiver, as if any rather nice person might step in and do the job. Let me hasten to add that I am not arguing against nannies, day care, or any of the cobbled-together arrangements that beleaguered working parents make so they can simultaneously raise and support their families. What I am saying is that tending is a vitally important task that shapes the health and character of children (and adults), and it should be recognized as such. I hope you will finish reading this book with a renewed respect for it.