DEDICATION

In a lifetime of fishing and hunting I have got by, only with a lot of help from my friends. Driving the back roads at night searching for a lost dog, or the barely whispered, Mark right in a foggy duck blind that brought the pintails into view, are some of the many remembered kindnesses.

I have learned a lot from my friends. Because of their special insights I have fished new waters, shot new birds, and walked game trails never imagined by me. To each of them I give a formal salute with a wooden spoon.

If you are lucky enough to know folks like this you will understand. Likely, you will have your own list of sportsmen and women, living or dead, who opened a door into that special part of the world inhabited by wild game and fish. My life and this book would be productions on a lesser scale without them. Good cooking, my friends: Edward H. Baird, L. Irvin Barnhart, E.G. Sandy Hall, J. Michael Hershey, Ben F. Vaughan, III.

2004 S.G.B. Tennant, Jr.

Published by Willow Creek Press

P.O. Box 147, Minocqua, Wisconsin 54548

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the Publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Tennant, S. G. B.

Wild at the table : 275 years of American fish & game recipes / S.G.B. Tennant, Jr.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-6234-3596-7

1. Cookery (Fish) 2. Cookery (Game) I. Title.

TX747.T4537 2004

641.692--dc22

2004015284

TABLE OF CONTENTS

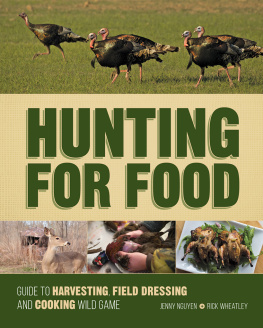

also Turkey, Partridge and Pigeon/Squab

also Coots, Rails, Cranes and Swans

also Moose, Buffalo and Big Horn Sheep

also Alligator, Squirrel, Raccoon, Frogs Legs and Rattlesnake

also Salmon, Pike, Steelhead and Pan Fish

also Snook, Grouper, Bluefish and Pompano

also Mahi Mahi, Swordfish, Cod and Halibut

also Crayfish, Scallops, Oysters and Conch

W hen construction started on Independence Hall in 1729, the good citizens of Philadelphia knew they were laying the foundation for American pride, American idealism and American democracy.

Just around the corner, The Blue Anchor Tavern stood as a familiar landmark, offering its clientele nourishment and diversion in the form of ale, seethed sturgeon and turtle soup. The vittles, like the sturdy hand-made cedar beams in the public house, were native born, grown up in the fields, rivers and woods of the new country.

Independence Hall. at this early date, was just another colonial office building. Merchants relaxing at The Blue Anchor ate game and fish without much comment, the way they had all their lives. This was Americas first food, and practically the only one available.

Everything that had gone before was prologue. What was about to follow, in both buildings, was revolutionary. Much of what we think of as early American history was already ancient by this time. The saga of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock and their first Thanksgiving in 1621 was a century old. Their now famous meal of roast duck, roast goose and just maybe a wild turkey had passed into folklore. Wild turkeys would have been a novelty, but domestic turkey, by this point, some 100 years after Columbus, were a familiar feature in British cookery.

The standard cookbook of the day, The English Huf-wife by Gervase Markam (published in England in 1615) repeated the established cannon of accepted British and European recipes familiar to the Pilgrims. The standard diet was defined by roast meats and breads, offering very little use of fruits and green vegetables.

Colonies similar to Plymouth were established in Virginia and New Amsterdam and each had learned some of the novelties of American wildlife such as clams, wild ducks, and for the first time for many, lawful venison! In fact, deer hunting was so enthusiastically pursued in Rhode Island that open and closed seasons, much like those in place today, were first imposed in 1646.

But the history of American game and fish cookery is a continuing work in progress, an emerging canvas expressing regionalism and diversity. The Spanish colony known as the City of New Orleans, formally organized more than a decade before 1729, was a beacon of Spanish, French, African, and Carribean diaspora cultures whose blending would eventually form the Creole culture of Louisiana. And their food was predictably unique. Mennonite emmigrants from Germany settled in Pennsylvania, creating another regional view of cooking that came to be known as Pennsylvania Dutch long before the American revolution.

By this stage the settlers had accepted and given names, not always correctly to the vast gallery of native game and fish species. The Spaniard Hernando Cortez, in 1539, saw great shaggy beasts in the hundreds of thousands thundering across the midwestern prairies, and pronounced them buffalo. The American bison has never recovered from this misnomer, and of course, has no kinships at all with the true buffalo of Asia and Africa.

In the early 18th century the tiny human population of the vast territory known as North America was a broad mix of European and British culture and culinary attitudes. Game and fish, to these immigrants, were seen as the food of kings in the old country, and represented an immense windfall without the hazards of poaching. As the colonists became accustomed to this luxury they tended to grow beyond the cookbook status quo that dominated game and fish cooking in 1729.

It is from this vantage point, or plateau, that we can stir through the ingredients and processes of American game and fish cookery as an emerging cannon of recipes. How we got where we are today is a story as diverse and unpredictable as the American experience in every other field of endeavor from music to literature.

THE COLONIAL PERIOD1729-1759

T he first organized fish and game gourmet society sprang up near Philadelphia in the colony called Schulykill in 1732. The company had a series of quaint rules, but regularly served shad, which some consider the founding fish of America. White perch and small game were also served to a membership whose recreational purpose was taking fish, shooting game, and preparing the same with their own hands.

Their Schulykill recipe for fried White Perch in clarified butter provided: Again, drawn or melted butter is made in perfect purity, without any of the usual addditions of flour and water.

At these elaborate ceremonial dinners, even today, the modern cooks adhere to the old technique. Skillets with yard-long handles hold several fish, which are flipped simultaneously and repeatedly until they reach a rich brown color. The charm of the club, of course, was not the planked shad, or even the fried white perch, but the focus on comraderie and game and fish preparation as an end in itself. As befits any organization with such a grand charter, the Schulykill Fishing Company is alive and thriving today.

English cookbooks were first published in Williamsburg, Virginia, as early as 1742, but they were merely retreads of the old formulas. The first modern cookbook, by Hannah Glasse, another English author, was

Next page