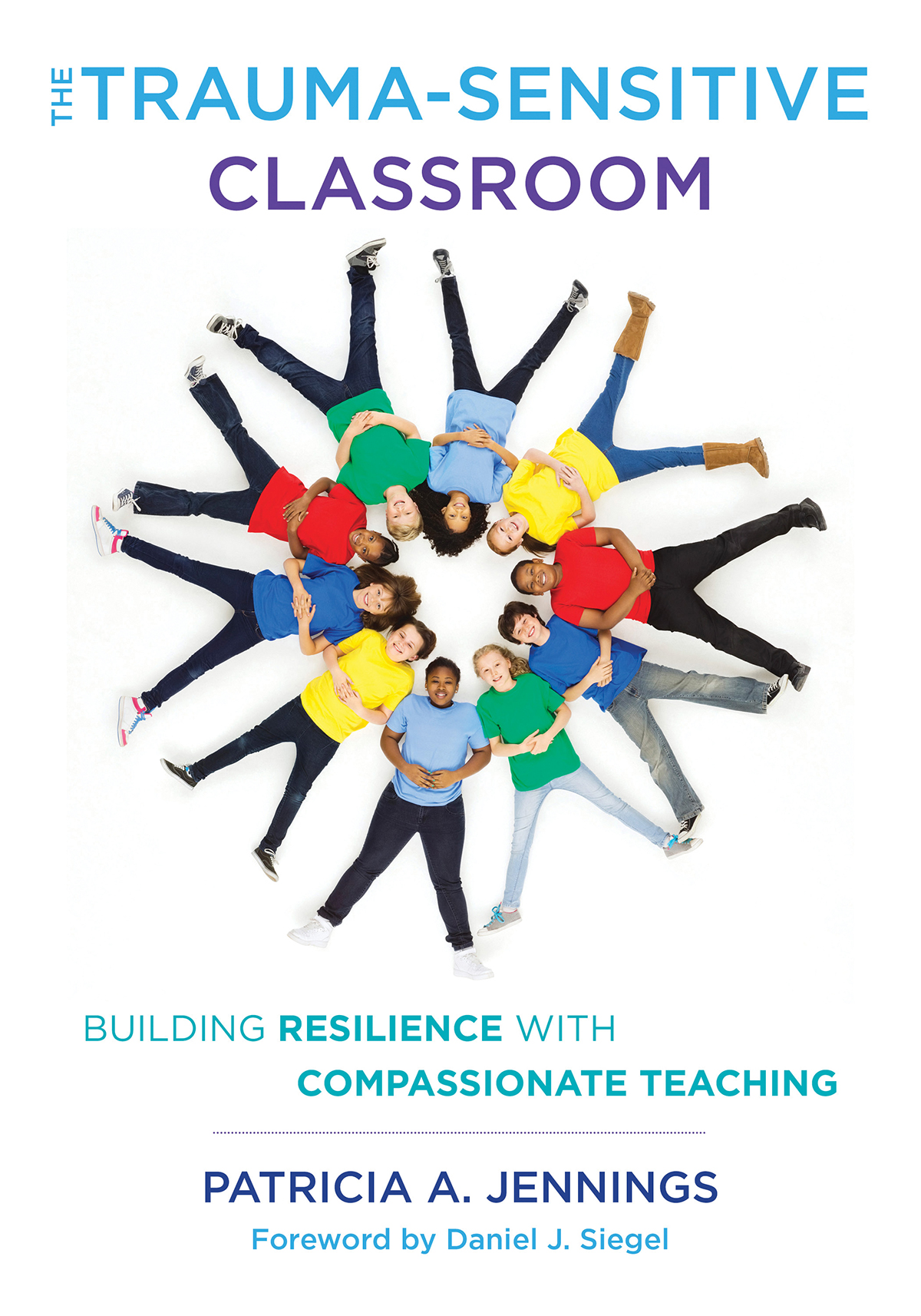

The Trauma

Sensitive Classroom

The Trauma

Sensitive Classroom

Building Resilience with

Compassionate Teaching

PATRICIA A. JENNINGS

FOREWORD BY DANIEL J. SIEGEL

W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

To my sisters Pam and Penny

together we traveled through a nightmare,

and survived holding hands.

I love you.

Gratitude

I would like to thank many people for helping this book become a reality. I could not have written it without your help. Special thanks to my husband, Andre, for taking such good care of me. Together we created a new model of relationships for one another. A deep bow of gratitude to my teachers His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, Roshi Joan Halifax, Matheu Ricard, Sharon Salzberg and Tara Brach. They have all helped inform this book in various ways. Colleagues Tamar Mendelson, Erica Sibinga and Amanda Moreno, who all work on interventions and research to help children and teens exposed to trauma and adversity provided information about their experiences that informed this book. Similarly, Alex Brown and Tawanna Kane who work directly with students needing trauma support were informants for this book. To all of you, I am deeply grateful for the important work you do and for your willingness to share your stories. Special thanks to my friend and University of Virginia colleague Jim Coan whose story about how one teacher made a huge difference in his life provided a wonderful example for this book. I am grateful to my therapist, Lewis Weber, and my therapy group who helped me open Pandoras box to let memories of a little girl come to life so I could write this book. Many thanks to Carol Collins, my wonderful editor who gently kept me on track and offered important suggestions that made this book what it is.

by Daniel J. Siegel

Educational experiences can shape a students life for a lifetime.

For some children and adolescents, traumaevents that challenge an individuals sense of physical, emotional, social, and moral safetyoften create alterations in their sense of self that can make opening to the benefits of the school environment quite difficult. Educators informed about the specific needs of pupils in their classroom can help everyone benefit. Teachers, other students, and the overall classroom climate are enhanced when the key insights of this important book are applied to working with traumatized pupils and creating a generative social environment in which everyone can learn. In this profoundly insightful book, written with scholarly rigor and personal sensitivity, Tish Jennings offers us an in-depth guide to understanding what traumatized students need to optimally learn both the knowledge that teachers convey, and the relational skills that a classroom environment can nurture.

Trauma can happen in a home, leaving a child with the paradox of being terrified of attachment figures to whom the child usually would be able to seek comfort and safety. But when the cause of the terror is the parent figure, the child has nowhere to turn. Attachment research reveals that such a fear without solution can lead to a fragmentation of the mind called dissociation. Under stress when such dis-connections of the usually associated thought, emotion, and memory processes within consciousness occur within a child, a teacher may only see from an outside view that a child is staring into space or seems to get lost in following directions. Fortunately, when educators know about dissociation as one example of traumas wake, and have insights into the role of attachment in the development of the mind, they can learn sensitive and effective ways of interacting with traumatized children that help them to focus and interact with others in pro-social ways.

Trauma can also happen in a community, again leaving a child with a feeling of terror, only this time the larger social world may feel unsafe. When violence is prominent in a neighborhood, for example, children often have their panic reactivity reinforced. Losing relatives or friend or neighbors from violence can create not only fear, but also loss. When unresolved, trauma or loss can make learning difficult.

In each of our brains rests a set of regions responsible for reacting to threat. These survival circuits activate a state of mind that shuts off being receptive to the input of others. Reactivity is a common state of those who have experienced trauma. Yet school ideally invites us to be receptively open, not reactively shut off. Optimal learning requires a receptive state of mind, not a reactive one.

But why would trauma, now that it is over and in the past actually have a lasting impact on us? One way to understand this is that the brain takes in experience as patterns of energy and information flow. This flow shapes the brains very structure in following way: Where attention goes, neural firing flows, and neural connection grows. If attention, the streaming of energy and information, is repeatedly shaped by a state of reactivity and alarm, then that state of mind or brain state actually activates genes, produces proteins, and leads to the growth of neural connections in very specific activated circuits. This is called neuroplasticity. Trauma, as an experience, activates neuroplastic growth that creates an excessively exercised and then grown threat circuitry. With intense and repeated neural firing, the brain rewires and that circuit grows in dominance. What this means is that a state of alarm is more readily activated with these repeatedly reactive states of trauma. For a traumatized student, a particular sight or sound or social situation can initiate the threat reactivity that, for a non-traumatized student, is simply an everyday non-significant moment or interaction in the school day.

Feeling unsafe activates the fight-flight-freeze-faint reaction to threat. This alarm state is the opposite of what optimal learning entailsan open, receptive state of engaging with the world. Even something as seemingly innocuous as getting an answer wrong on a test can activate a sense of not being acceptable, not being accepted, being excluded, and, as a consequence, the feeling of threat is initiated. One trauma-based reaction would be to run from such experiences and avoid taking a chance in learning; another trauma-influenced stance might be to faint or collapse, meaning to shut-off and dissociate in reaction to such challenges. A third would be to become overly aggressive to fight against a constant feeling of threat. For someone with a history of trauma, this priming of the threat-state of alarm can temporarily shut down the openness to take chances and to engage with others that are needed for an optimal learning process to unfold.

While hearing these details may itself feel overwhelming if they are new, its crucial for every educator to learn about them and know how best to work with reactivity and help guide traumatized students to a receptive state of mind in which learning can occur. Unfortunately, more and more children are experiencing trauma, and even the state of our world is so filled with the news of threat that learning these important insights and strategies has never been more important.

Next page