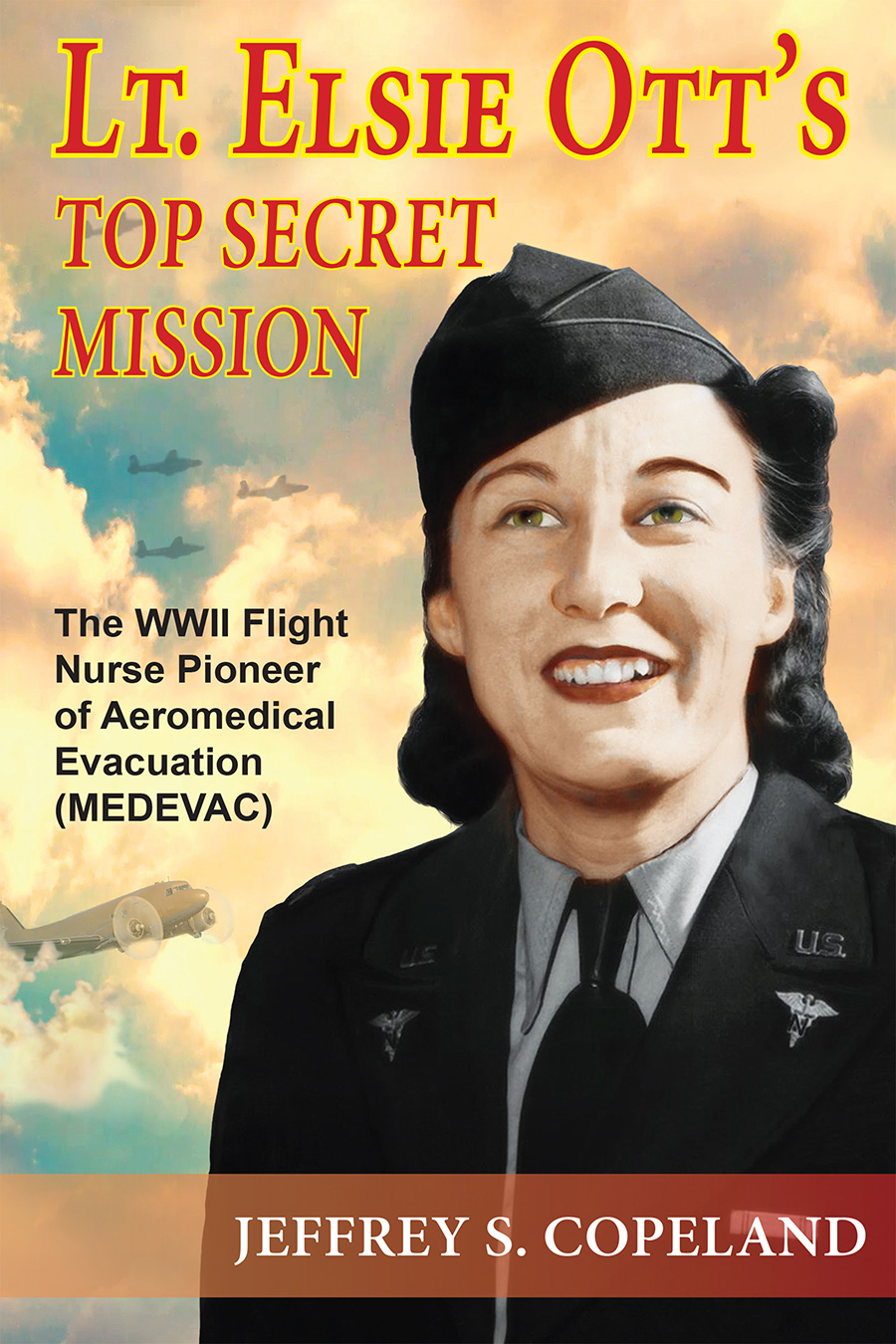

Lt. Elsie Otts Top Secret Mission

The WWII Flight Nurse Pioneer of Aer omedical Evacuation (MEDEVAC)

by

Jeffrey S. Copeland

Paragon House

First Edition 2020

Published in the United States by

Paragon House

www.ParagonHouse.com

Copyright 2020 by Paragon House

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher, unless by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages.

Cover Design by Mary Britt

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Copeland, Jeffrey S. (Jeffrey Scott), 1953- author.

Title: Lt. Elsie Otts top secret mission : the WWII flight nurse pioneer of aeromedical evacuation (medevac) / by Jeffrey S. Copeland.

Other titles: WWII flight nurse pioneer of aeromedical evacuation (medevac)

Description: First edition. | [St. Paul] : Paragon House, 2020. | Summary: Lt. Elsie Otts historic, top-secret aeromedical evacuation mission in January of 1943 helped pave the way for a dramatic change in how wounded soldiers received vital medical care. Lt. Ott was given the task of transporting five severely wounded and ill soldiers from Karachi, India to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C. During this grueling journey, she and her patients faced German fighter planes, guerilla snipers, altitude challenges, logistical complications, and more.-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019044332 (print) | LCCN 2019044333 (ebook) | ISBN 9781557789419 (paperback) | ISBN 9781610831222 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ott, Elsie S., 1913-2006. | Aviation nursing--United States--History--20th century. | Transport of sick and wounded--United States--History--20th century. | World War, 1939-1945--Participation, Female. | World War, 1939-1945--Medical care. | United States. Army Nurse Corps--History. | United States. Army Air Forces--History. | Nurses--Biography.

Classification: LCC D807.U6 C67 2020 (print) | LCC D807.U6 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/7573--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044332

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044333

Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSIZ39.48-1984.

For my daughter, Crystal Lynn

Authors Note

Today, it is common for airplanes and helicopters to transport individuals from hospital to hospital, to remove those who need care from accident scenes, to transport organs for transplant, and to deliver vital medical supplies when disasters strike. Who among us doesnt know of a friend, co-worker, relative, or loved one who has been touched in some way by these life-saving services?

According to the Association of Air Medical Services, over 550,000 medical aircraft transports occur each yearand the number is climbing steadily. Since WWII, aeromedical evacuation teams (today shortened to MEDEVAC) have been established all over the globe, providing medical care and coverage that has saved millions of lives.

And, the major spark for all of this began with the work of Lieutenant Elsie S. Ott. Lt. Ott sparked an evolution in medicine that has saved millions of lives in a period from just before the conclusion of WWII to the present. Though she was recognized for her pioneering work during her lifetime, today few beyond military historians recognize her name, and even fewer know the full story of her ground-breaking journey. Much of the work she did was tucked away for decades in classified military documents.

The adventure that follows is based on a true story, the details of which were gathered from archives, records centers, and military documents of the era. Because many of the records involved here are still classified, some names have been changed, and other characters are composites of several.

However, the bravery, heroism, and courage of the individuals presented here are real and described as they occurred during this historic mission.

JSC

Contents

Chapter 1

No Use Worrying

1825 ZULU, January 17, 1943

(51 miles east of Aden, Saudi Arabia)

Large plumes of black smoke erupted from the right engine, almost totally covering the center portion of the dull, silver wing.

Only moments before, our C-47 Transport had shuddered violently as we heard a low, gurgling sound followed by a series of loud pops that seemed to be coming from just outside the right bank of windows. The smoke followed almost instantly as what appeared to be a gas or oil ring expanded and arched all the way across the width of the wing, resembling a grass fire spreading rapidly in a swift wind.

I had started to scream when the C-47 suddenly picked up speed and banked downward as the right propeller stopped, and thick, now greyish-black smoke covered the windows. All happened so fast two of my patients lying on cots off to my left were thrown to the floor and rolled toward me, both of them crashing together at my ankles, causing me to topple back against the wall. Completely stunned, none of us uttered a sound.

Sergeant Rigazzi, who had been seated just ahead of me, held tight to a leather strap between the windows as he turned his head and stared my direction. His mouth opened as if he were going to speak, but before he could, the angle of our dive increased even more, slamming us together. His hand slipped from the strap. I grabbed his arm and pushed hard as I could, but he lost his balance and fell to the floor with a thud.

My ears plugged, so much so the roar of the engine became faint, like the steady, low drone of a truck motor at idle. I felt dizzy, a wave of nausea climbing my throat. Sergeant Rigazzi finally spoke, Lieutenant Ott, what... What do we...? I just shook my head and blew out three quick breaths. Our attention was drawn back to the floor as several dozen C-ration cans dislodged from their carton, rolled, and bounced toward us, settling around our feet.

Captain Goldman, my acute tuberculosis case, slumped in a chair anchored to the left wall next to where Sergeant Rigazzi had been only moments before. The angle of our descent caused his legs to dance back and forth on the floor in front of me. He appeared unconscious, but I couldnt tell if it was from injury or frightor both.

Jerking my head to peer out the windows again, I saw the area covered by smoke had doubled in size and was moving toward the window directly in front of me. Our angle of descent was so severe I couldnt see the sky.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the co-pilot reach up and rip open the sheer curtains separating him and the pilot from the rest of us. I saw the pilots right hand stiffen and roughly push forward the control next to his knee. While he did so, Private Scalini, who had tumbled awkwardly and head-first from his seat, clutched my legs and moaned as a thick, perfectly circular pool of blood formed around his head. He looked up at me, his eyes pleading. I couldnt move, but not because of the steepness of our dive. I was frozen by the unknown of the moment and dug the heels of my shoes into the floor while arching even tighter against the side of the plane.

In the midst of this chaos, my mind shot back to the words of Nurse Rose McCall, Head Nurse at Barksdale Army Air Field Station Hospital in Louisiana, where I had been given my final training before being shipped overseas. The day Nurse McCall found out I was to be stationed in India, she took me aside and offered several pieces of advice, part of which had to do with the perils of travel, especially flight. Ive traveled all over the world in my day, she said. And I can tell you nothing will age you like being aboard a plane. But you cant worry about it. Doesnt do any good. Wont matter.