FOR

M.C.W. & E.C.W.

This second revised edition published in Great Britain by Prospect Books in 2010 at Allaleigh House, Blackawton, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7DL.

The first revised edition was published by Prospect Books in 1999

The Book of Marmalade was originally published by Constable & Co. Ltd., London, in 1985.

Copyright 1985, 1999 and 2010, C. Anne Wilson.

C. Anne Wilson asserts her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-903018-77-4

ePub ISBN: 978-1-909248-27-4

PRC ISBN: 978-1-909248-28-1

Designed and typeset in Hoefler Text by Oliver Pawley and Tom Jaine.

Printed in Malta by Gutenberg Press.

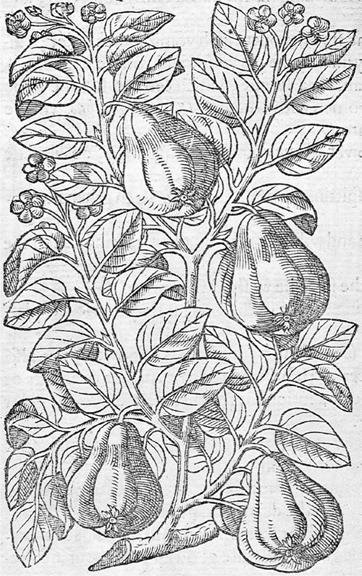

Quince tree. J. Gerard, The Herball , 1597.

E very few years in the correspondence columns of The Times the argument about marmalade is resumed. Its champions write in to say it was invented by Janet Keiller, by Mary, Queen of Scots, by the Portuguese, and they cite erudite works telling about the uses to which it was put. It seems almost unsporting to produce a book which will settle the argument once for all. But the long, complicated story of marmalade and its antecedents has fascinated me for some time, and now I have succumbed to the temptation to write it out and share it.

When the publishers asked to have the story brought up to date with information on marmalades place in the world today I had the chance to delve into its very recent history and realised that this is an ongoing affair, and that new fashions in marmalade are continuing to emerge, not only in Britain, but in English-speaking countries overseas. In some ways the wheel has come full circle. Marmalade was a very special gift in the reign of King Henry VIII. In the 1980s the premium sector, supplying expensive marmalades intended for the food-gift market, is the most buoyant part of the marmalade trade. But whereas we once imported our marmalade from Portugal, Spain and Italy, now we send it as an export all over the world.

Many friends and colleagues have been kind enough to contribute facts or recipes, or both, to this study. I should like to express special thanks to Dr Wendy Childs, Alan and Jane Davidson, Professor Constance Hieatt, Janet Hine, Helen Peacocke, Jennifer Stead, Rosemary Suttill, and Beth Tupper. My thanks are due also to the following firms and their representatives, who sent me useful material on several aspects of marmalade manufacture: Baxters (Mr W.M. Biggart), Chivers (Miss E. Greenwood), Frank Cooper (Mrs C. Hooper), Crosse & Blackwell (Mr R.H. Starling), Elsenham (Mr A.J.G. Blunt and Ms G.Sinclair), Fortnum & Mason (Mr K. Hansen), Keiller (Mr C. H.Blakeman), Robertson (Ms J. Meek), and Wilkin of Tiptree (Mr I.K. Thurgood).

Most of the older recipe books consulted are among those in the Blanche Leigh and John F. Preston collections of early cookery-books in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. Nearly all cookery-books from Elizabethan times onwards contain marmalade recipes, but the ones listed in the bibliography are the books and the editions which were used in compiling the present text. Individual page numbers have not been cited, as most of the books have indexes, so the keen marmalade-sleuth can find the recipes without difficulty in contemporary copies of the books, or in modern facsimile reprints.

Twenty-one of the most significant early recipes are printed in full in a separate section on historic recipes (pp. ). The modern recipes which follow are divided into two sections, one for marmalades, and the other for a wide range of meat dishes, sauces, puddings, cakes, pastries, etc. in which marmalade is an ingredient.

Preparing this book has been a pleasant and interesting task, and I hope it will give pleasure to its readers.

C.A.W.

Leeds

May 1984

M armalade, with its long history and special traditions, is now under threat in the British Isles. The large-scale commercial manufacturers report dwindling sales year on year, and reckon that the vast majority of their customers are middle-aged or well beyond, and the younger generations have never acquired a taste for this conserve - or for the breakfast habits of their grandparents. The number of long-established independent producers with family traditions has also dwindled. Premier Foods has absorbed Cooper, Keiller, Robertson and others. But the large conglomerates also readily sell off well-known brands if retaining them does not suit their current aims or financial position. So although I have updated parts of chapters seven and eight, the commercial picture may be quite different in a few years time.

But the rearguard is fighting back. Duerrs has instituted National Marmalade Day, celebrated on 10 March (the date in 1495 of the earliest record available, at the time of the first edition of this book, for the arrival at an English port of Portuguese quince marmalade). An annual National Marmalade Festival is now held in late winter at Dalemain House in Cumbria, attended by enthusiastic home-makers of marmalade from all over the country. They enter their products into competitions, with a large choice of different categories, and some 600 entries were claimed for 2010.

Marmalade is also making some progress elsewhere in the world. The Japanese have now acquired a taste for it, and enjoy it not only on toast, but also mixed with yoghurt or dissolved in hot black tea or water. This conserve can without difficulty be made locally Japan is home to many different types of citrus tree, and Michito Nozawa, my informant, kindly sent me two jars of her home-made marmalade. One was based on Dai-dai (a close relation of the Chinese progenitor of our Seville orange, which may itself have originated as a cross between the pomelo and the tangerine); and the other made from Yu-zu, a sweeter, very fragrant type of orange.

Marmalade in Britain has developed and changed a great deal over the centuries and perhaps in future most of it will be prepared from sweeter citrus fruits. Meanwhile, in todays world of fusion foods, new ideas for combining tangy Seville orange marmalade with other foodstuffs must surely emerge. Long live marmalade!

C.A.W.

Leeds

June 2010

Next page