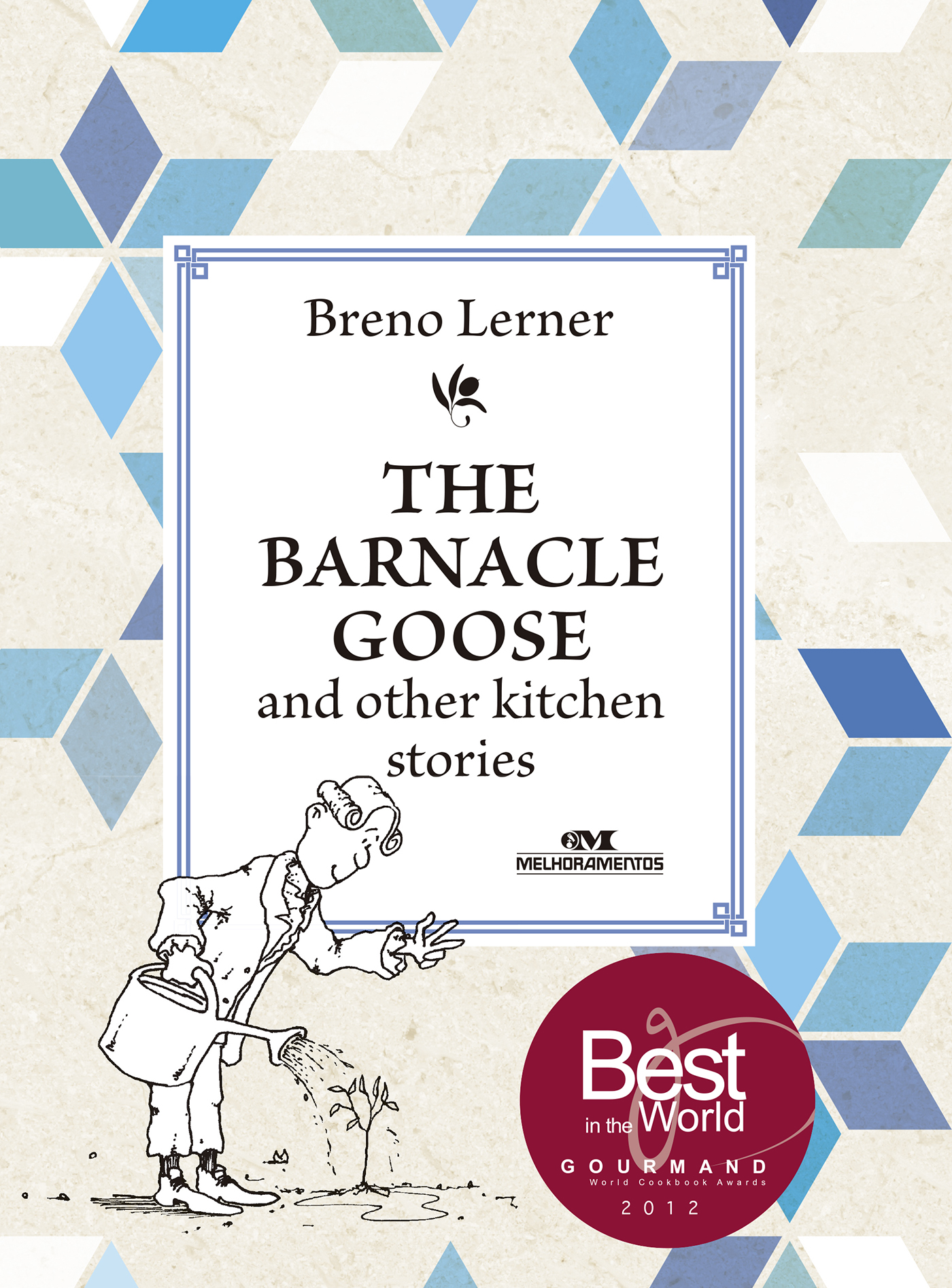

THE BARNACLE GOOSE

and other kitchen stories

Breno Lerner

THE BARNACLE

GOOSE

and other

kitchen stories

Translation by Renata Lucia Bottini

Cover: Erika Kamogawa

Illustrations: Domingos Takeshita

Graphic Design & Desktop Publishing: Erika Kamogawa

2011 Breno Lerner

Publication rights:

2011 Editora Melhoramentos Ltda.

1st edition, september 2011

ISBN: 978-85-06-06816-8 (printed work)

ISBN: 978-85-06-00428-9 (digital / english)

Customers service:

Caixa Postal 11541 CEP 05049-970

So Paulo SP Brasil

Tel.: +55 11 3874-0880

www.editoramelhoramentos.com.br

sac@melhoramentos.com.br

To Suely, Carolina and Vanessa the women in my life.

To my grandmothers, from whom I learned everything.

In memory of my father, who taught me everything.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I am a storyteller. I love to tell stories and fibs, even better if they are related to cookery.

Everything started at my Babe Claras home, seeing her industriously preparing the meals and classic Jewish food for each of the holidays and for the Sabbath. The passing of the years has warned me that all that heritage might be lost, and I started to record it, transforming abissele (a little, in Yiddish) in cups and shticale (a small piece) in grams.

Time went by and curiosity forced me to look for and register stories and origins of each dish and ingredient.

At some point in the 1980s, Jairo Fridlin, of Sefer bookstore, asked me why didnt I begin to tell those stories to others. Well, my dear Jairo, look at the sort of trouble you got me in...

Since that time there were workshops, lectures, TV shows, columns in magazines, newspapers and sites, three books already published; in short, my activities have increased, my interests have multiplied, and I started cooking to better illustrate the stories I was telling. Now I am a storyteller pretending to be a cook.

In order to better tell the stories, I started to dedicate all available time to research and, dear friends, what a terrible nightmare it has been to try and find sources and origins. More than other cultural aspects of history, cuisine and its ingredients usually have more than one source, more than one history, more than one version. When I met such situations, I tried to put on record the version that seemed most proven or plausible in the light of the facts; but in some rare cases I admit having chosen the one that seemed more fun.

So, my friends, in these stories I did not intend the precision of archaeological cookery, but to bring up some interesting features to give the readers a better understanding of what and why they are eating, and to do so in a pleasant and fun way, whenever possible.

I must give very special thanks to my editors in magazines, shows and sites, who greatly contributed to my research with their knowledge.

Still more special thanks are in line to the Jewish Cultural Center, my home and my kitchen, which in the last few years allowed me to develop researches, programs and workshops, Jewish or not, plenty of them registered in this book.

A warm and unique thank you to my mother who has always supported my successes and mistakes silently.

Breno Lerner

Because Jews are not allowed to pronounce or copy the Creators name,

I have adopted the conventional spelling G-d.

THE RECIPE BOOK

A TRUE GASTRONOMIC TREASURE, COMPILED AT THE TIME OF

THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS, REFLECTS THE FASCINATING STORY

OF THE ARAB WORLD FUSION WITH ITS MEDIEVAL RECIPES.

One thousand years ago, the cultured prince of Alepo, Saif al-Dawlah al-Hamdani, ordered poet Abu Muhammad al-Muzaffar ibn Sayyar a book to describe the gastronomic wealth of the time. There were good reasons for that, because gastronomic culture was almost an obsession among Sassanian rulers, who promoted cooking tournaments and palace recipe contests. By the way, the next dynasty, the Abbasids, kept this custom, moving the capital to Baghdad and causing the cultural renaissance of the region.

Being a noble descendant of ancient dynasties himself, the author had access to all the important families of the time and managed to get the recipes used at the palaces of caliphs, princes and everyone who was someone. In the book, which contains a total of 35 recipes, there are some treasures, such as the personal recipes of the caliphs Al-Mahdi, the savior, Al-Mutawakkil, the builder, and Al-Mamun, the rebellious son of the great Harun al-Rashid, apart from culinary stories of Ibrahim al-Mahdi, poet and gourmet.

Little of this masterpiece reached our time. Only three complete manuscripts and an incomplete fourth reveal the culinary wonder of that which was the richest city of its time. Unfortunately, that is not enough for us to understand the true gastronomic empire that Baghdad probably was.

Curiously enough, we did not find recipes of hummus, baklawa,because at the time the fusion of the Persian and Muslim worlds was not so strong yet. Nevertheless, we do have recipes the names of which honored the potentates of that time, such as Haaruuniyyah, Mamuuniyyah, Mutawakkiliyyah e Ibraahimiyyah. There is even one named after Mamuns wife, Buraniyyah, one of the few that are still known nowadays and which, by the way, is one of the several known versions of eggplant with beef.

As a matter of fact, one should note the small number of eggplant recipes in the book. Nowadays it is known among Arabic peoples as sayyid al-khudaar, the lord of vegetables, but at the time it was a recent import from India, not very well known and with a bitter taste.

As an anecdote the book reports that one Bedouin, when introduced to the eggplant, said: that eggplant thing has the color of a scorpions belly and tastes like its ass Doctors of the time have even assigned certain diseases to its consumption.

Even so, we found seven eggplant recipes in the book, two of them entitled Baadhinjaan Buran, Eggplants of Buran, named after the wife of the caliph, perhaps she was the first noble to spread their use, most likely in the memorable banquet of her marriage, which is described in the book as a landmark of historical luxury and refinement.

A third recipe, also attributed to Buran, deals with slices of eggplant fried and sprinkled with pepper, cumin and, astonishingly, minced rue.

Known as rue by the Persians, this herb was used as a spice, a custom probably originated in India. Interestingly, doctors of the time already warned that it could modify the female menstrual cycle and, therefore, its use was not advisable for pregnant women or those who intended to become pregnant.

It is also worth to learn a little about the food of the pre-Islamic Arab nations, which merged with Persian traditions and created that wonderful cuisine.

Although plentiful, pre-Islamic food was rather monotonous. Everything revolved around dates, barley, milk and dairy products, to the point of their having different words for dates with milk (majii), dried dates with milk (siqal), pitted dates with milk (watiiah) and smashed dates with milk (wajiiah).