The Kinetoscope: A British History

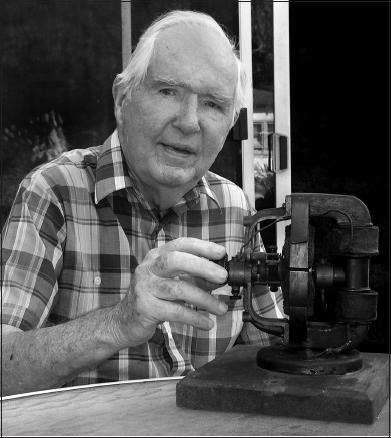

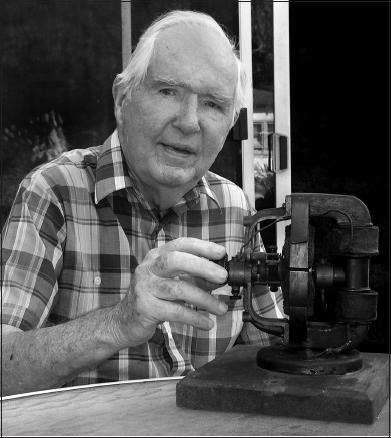

This book is dedicated to the memory of Ray Phillips (19202017) whose unique work in documenting and replicating the Edison Kinetoscope has contributed greatly to our understanding of the earliest years of the moving image.

The Kinetoscope: A British History

Richard Brown and Barry Anthony

with an additional chapter by Michael Harvey

Foreword by

Charles Musser

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Kinetoscope: A British History

A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 0 86196 730 8 (Paperback)

ISBN: 0 86196 931 9 (Ebook)

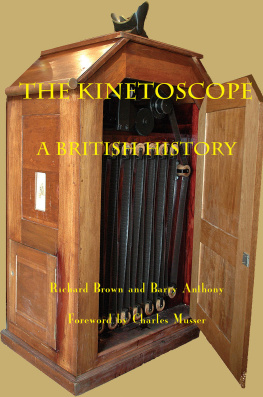

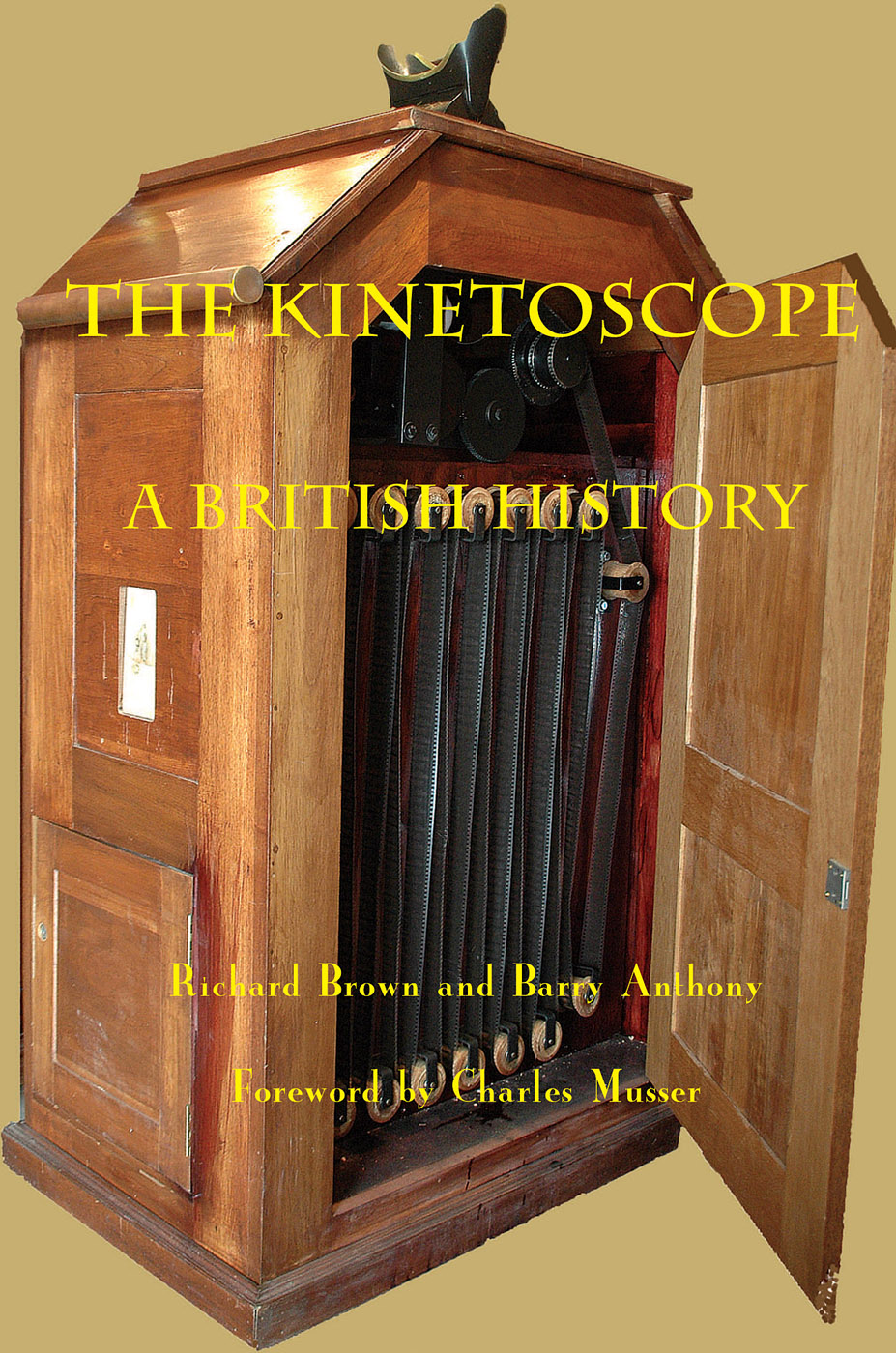

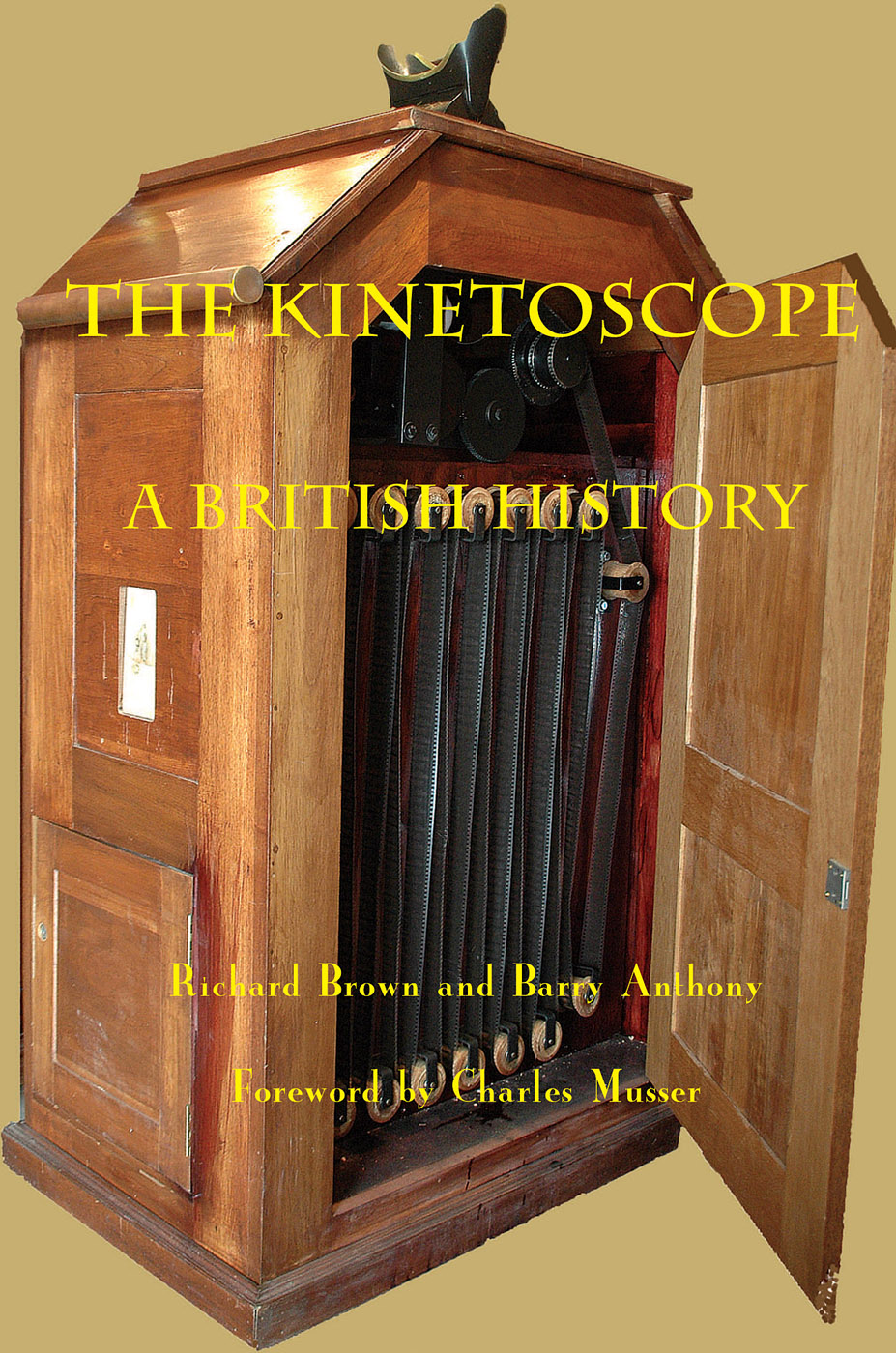

Front cover: A reproduction kinetoscope constructed in 2015 by Suphachai Worthong, and exhibited at the Thai Film archive.

The right of Richard Brown to be identified as author of of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The right of Barry Anthony to be identified as author of of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The right of Michael Harvey to be identified as author of of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by

John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 205 Crescent Road, East Barnet, Herts EN4 8SB, United Kingdom e-mail:

Distributed Worldwide by

Indiana University Press, Herman B Wells Library350, 1320 E. 10th St., Bloomington, IN 47405, USA. www.iupress.indiana.edu

2017 Copyright John Libbey Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

Unauthorised duplication contravenes applicable laws.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Contents

by Charles Musser

by Michael Harvey

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the authors wish to thank David Robinson for his invaluable help and encouragement during the early stage of this project. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the late Frank Andrews, Jean Anthony, the late John Barnes, Stephen Bottomore, Adam Carter, Reference and Information Librarian, Bury Library; Richard Crangle, Associate Research Fellow, University of Exeter; Bryony Dixon, British Film Institute; the late Geoffrey Donaldson; Frank Gray, Director of Screen Archive South East, University of Brighton; Paul Israel, Director and General Editor of the Thomas A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University; Elizabeth MacKinney; Luke McKernan, Head Curator, News and Moving Image, British Library; Charles Musser, Professor of American Studies, Film and Media Studies and Theatre Studies, Yale University; Simon Popple, Deputy Head, School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds: Deac Rossell, Lecturer in European Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of London; Irfan Shah; Paul C. Spehr, former Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress; and Madeleine Stannell.

For the final chapter, Michael Harvey would like to thank former colleague, Toni Booth, at the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford for her help in accessing the Science Museum registry files and her patience in dealing with various enquiries and requests. The quotations from the Science Museum registry files are by kind permission of the Trustees of the Science Museum. Grateful thanks go to the late Ray Phillips and his family for their kindness in allowing quotes from his letters, and to Jeff Oliphant who gave invaluable assistance and insights into American Edison collectors. Thanks also to Stephen Herbert for so generously sharing information and to Gordon Trewinnard for his kind co-operation.

Finally, our gratitude to Le Giornate del Cinema Muto for making the publication of this book possible.

Foreword

Charles Musser

R ichard Brown and Barry Anthony have been long-standing contributors to the intellectual formation focused on the study of early cinema, which emerged as a dynamic field of investigation around the time of the 1978 FIAF Conference in Brighton England and continues to this day.

Edisons peephole Kinetoscope dominated the field of motion pictures for less than two years (189495). The several books that have been written on the subject have focused on the United States and concentrated in large part on motion picture production.inept when it came to effectively exploiting the Kinetoscope in England. By the time that Franck Maguire and Joseph Baucus had taken over, any possibility of a cohesive marketing plan was lost. Maguire & Baucus made credible efforts, but what soon occurred was a disorganized free-for-all. Local entrepreneurs most notably R. W. Paul began to make knock-off Kinetoscopes and often sold them using Edisons name. While some dealers made illegal dupes of Edison films, Birt Acres and Paul produced an array of innovative short films that could be used in Edisons (and Pauls) Kinetoscopes and featured British and European subject matter. In short Brown and Anthony show how a fledgling infrastructure developed using the Edison film gauge as a standard; and it was this standard that would ultimately prevail worldwide, in part because it flourished outside Edisons control. In other parts of the world, competing motion picture systems often used a different format and/or a different sized film gauge. In the United States, this included Charles Chinnock with his own version of the Kinetoscope, the Lathams with their Eidoloscope system, the Veriscope, and the American Mutoscope Company with its large format cameras and Biograph projectors. In France, the Lumires, Lon Gaumont, Henri Joly and others also employed different film formats. The English, in contrast, pursued extensions of the Edison system and this provided the basis for what ultimately prevailed worldwide.

Given the various British challenges to his Kinetoscope business, we should not be surprised that Thomas A. Edison and his associates were deeply concerned about the imminent invasion of British projectors and films as the new era of projection began. Consider the opening night programme of Edisons Vitascope at Koster & Bials Music Hall on 23 April 1896. Three films by Birt Acres were listed on the programme though only one of them was shown. They screened five others, all of which were made by the Edison Manufacturing Company. The unfamiliar British films would have received a warm reception; instead, the Vitascope people attacked their country of origin. The first film to be projected was a tinted print of Umbrella Dance, with the Leigh sisters. Dance films had been a popular Kinetoscope genre, and the Vitascope programme began by reprising it by featuring two American ladies. Next came Acres Rough Sea at Dover an English film which seemed to wash away the lovely dancers and threaten the spectators in the front rows. This inundation produced a fight, for it was followed by Walton and Slavin: a burlesque boxing bout between the long and the short of it the short one being a stand-in for John Bull (England) and his rival evoking Uncle Sam (the US). Next came the Finale of 1st Act of Hoyts Milk White Flag

Next page