Colour Films in Britain

Colour Films in Britain

The Eastmancolor Revolution

Sarah Street, Keith M. Johnston, Paul Frith and Carolyn Rickards

Figures

Tables

We are extremely grateful to the many people and institutions who have supported our research for this book. The project was made possible by a Research Grant awarded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/N009444/1). We are also indebted to the British Film Institute, in particular Kieron Webb who advised us on the many fascinating issues concerning the preservation and restoration of colour films. Candy Vincent-Smith and Massimo Moretti at Studio Canal UK were extremely helpful in assisting us with our investigations into colour film titles associated with the company, as well as giving us access to archive files on specific films. During the projects lifetime (201619) we benefited from other partnerships, particularly with the Colour Group (GB) and Elza Tantcheva-Burdge, with whom we collaborated on their Colour in Film annual events which provided a wonderful way to connect with other researchers and film professionals. The staff at the East Anglian Film Archive, particularly Angela Graham and Pete White, allowed us to view a range of amateur films and materials which made colleagues who have been interested in our research. Rebecca Barden at Bloomsbury has been an enthusiastic editor, and we are very grateful to the production team who worked so efficiently on our book. Finally, we thank our friends and families for helping and supporting us in many ways throughout the project.

Paul would particularly like to thank: Jane Fernandes, Anne and Paul Frith, Paul Hexter, David Jones, Sean Kelly, Robert Manning and na Phillips.

Keith would like to thank Beccy and Ewan, June and Sam Johnston, and Alan Colquhoun, and his colleagues at UEA.

Carolyn would particularly like to thank Dennis, Anja and Sarah for all their continued love and support, and special mention to Stuart and Isaac for being everything and more.

Sarah would like to thank Sue for being with me all the way on another journey into colour, and to her colleagues at Bristol and at Screen.

Keith M. Johnston and Sarah Street

This book explores the impact of Eastmancolor film stock on British cinema. While colour filmmaking today is ubiquitous, in the twentieth century its introduction was a story of intermittent trial and error, intense debate and speculation before gradual acceptance. The reasons for this were multifarious, involving the higher costs of photochemical processes such as three-strip Technicolor, as well as the persistence of taste cultures which appreciated black and white films as the norm. In the 1950s, however, the introduction of Eastmancolors cheaper, single-strip stock that could be used in any camera revolutionized the ways in which colour films were made. In its wake many film industries converted to colour which over the next thirty years became the dominant aesthetic choice for filmmakers and audiences. The books focus is on how British cinema, its filmmakers and other professionals adapted to one of the most important technical innovations in film history.

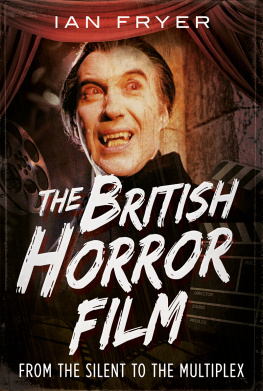

The Eastmancolor Revolution constitutes a fascinating case of how a game-changing new technology was experienced after decades of market domination by black and white films. Yet the change did not happen overnight, with the transition to colour constituting more of a long revolution in the sense that it was not until the late 1960s that the majority of films were shot in colour. Revealing the full complexity of the rise of colour cinema in Britain revises long-held assumptions that it was purely a response to competition from television, or that its adoption was straightforward. While some studios embraced colour in the 1950s with enthusiasm, notably Hammer with its range of horror films, others such as Ealing were more cautious. We examine the full economic and aesthetic consequences of the shift towards colour films in Britain that was consolidated in the 1970s and never looked back.

Despite the success of the revolution in colour production, the long-term influence of Eastmancolor remains largely unknown, apart from Hammers output or films notable for their striking colour motifs such as Dont Look Now (Nicolas Roeg, 1973), as seen in the opening sequence with the disturbing red spill effect that features on the cover of this book. While Dont Look Now is renowned for its distinctive chromatic style, as we demonstrate, the corpus of British colour films produced between 1955 and 1985 is far more extensive and varied when analysed from the perspective of colour. Freed from having to operate within the strictures of Technicolors colour consultancy service which had guided the use of that process in the 1940s and early 1950s, filmmakers using Eastmancolor could experiment as they wished. With this in mind, we evaluate what they achieved, working with the stocks creative and aesthetic possibilities. The look of Eastmancolor was different from Technicolor in that it rendered contrast more sharply but colours were in general less vivid, although the post-1968 faster stock became capable of rendering a richer, less grainy chromatic range. With reference to many films and genres, we investigate in the following chapters how changes in stock affected aesthetic practices and approaches to narrative and genre in British colour films, highlighting their variety, chromatic range and aesthetic sensibilities. Although many of the conventions established during the Technicolor years persisted, Eastmancolor films took advantage of new technical developments such as widescreen, ever faster stocks and new generations of technicians, costume, production designers and other creatives who were keen to explore the full spectrum of chromatic expression, while colour was also used to enhance the visual impact of films set in the past and future.

As well as focusing on colour expression in mainstream film genres we consider the significant, parallel impact of Eastmancolor on artist filmmakers, documentarists, amateur filmmakers and advertisers, among others. These examples demonstrate different paths and timescales; for example, amateur film producers used Monopack colour film earlier than the mainstream, so many of the debates around the use of colour were initiated in amateur publications of the 1940s. Artist filmmakers were eager to expand the experimental qualities of colour, from hand-painting and film scratching to the use of multiple exposures and filters. Finally, we explore the gradual shift to colour film restoration from the 1980s, after decades of preserving film prints in black and white. Colour continues to be a topic of recurrent national and international debate, fuelled especially by digital capacities for colour creation, manipulation and its role in the restoration of historically significant colour films.

The British experience of Eastmancolor is particularly striking in terms of its relative neglect in assessing British cinemas historic engagement with colour filmmaking. The literature on colour films has expanded over the last fifteen or so years, including studies on silent cinema (Yumibe 2012; Street and Yumibe 2019), an historical overview (Misek 2010), critical studies (Coates 2010; Brinckmann 2014) and collections of essays on theory and archives (Dalle Vacche and Price 2006; Brown, Street and Watkins 2013; Flueckiger, Hielscher and Wietlisbach 2020). Other studies have concentrated on early Technicolor in the USA (Higgins 2007; Layton and Pierce 2015), while the most extensive existing study of colour films in Britain emphasizes the silent era and Technicolor in the 1930s and 1940s (Street 2012). The technological details of other processes have been documented and described by historians (Cornwell-Clyne 1951; Coe 1981; Haines 1993; Flueckiger, Timeline of Historical Film Colours: http://zauberklang.ch/filmcolors/). But apart from a study of the early years of Eastmancolors technical development in the USA (Heckman 2015) there has been no thoroughgoing, book-length study of Eastmancolor. A number of publications are available on film preservation and restoration, but again the focus tends to be on non-UK film, as featured in the

Next page