Contents

A DIVINE STINK

Garlic in History, Lore, Medicine, and More

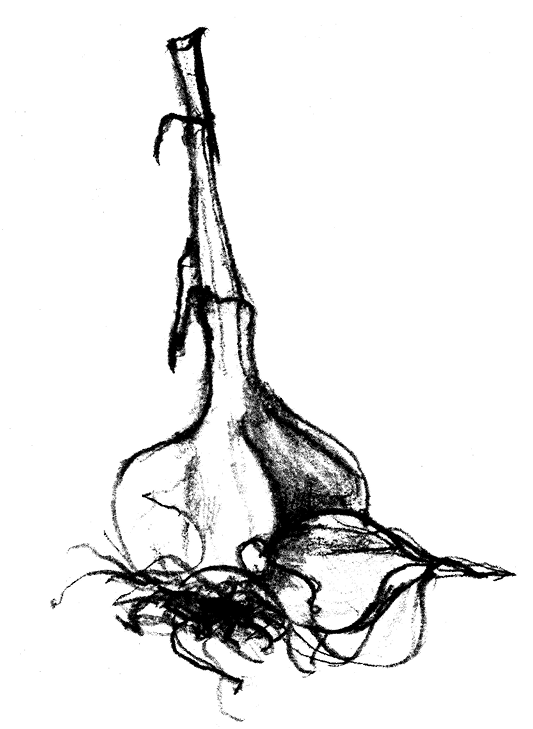

The bulb, an oriental palace shrouded in gray and lavender paper, splits open into a heap of wedge-shaped packets...

DAVID YOUNG, Chopping Garlic

My garlic bulb, freed from the earth by my trusty trowel, is a moon more than a palace, a pearly orb with smears of dirt making a miniature Sea of Tranquility on its newborn skin. Its not as round as a moon, but it is undulating and sensual, with papery curves that hide Draculas-fang cloves, their flavor so pungent that if I bite into one right away, it will sear my tongue and burn all the way down my throat.

But I wont do that. Garlic needs to mature and ripen to develop its best flavor, unlike carrots or parsnips or potatoes, which are at their crisp and sweetest best soon after theyre pulled from the ground. Garlic is an opposite sort of root vegetable, whose taste improves with some age, becoming deeper and more layered.

Ive cooked and savored this divinely odorous bulb, botani-cally known as Allium sativum, for many more years than Ive grown it, but growing it has made me respect it. Its one tough little dude, a survivor with a history as long as the potato, and like the potato its generally taken for granted. Its seen the rise and fall of civilizations and cultures and has made an appearance in the life of almost everyone whos ever lived. For about ten thousand years garlic has been many things: in Neolithic times it was a dependable food that could be kept fresh and edible in a cool cave for months. Its been a flavoring, a giver of strength, a healer, and a preventer of disease, and today its being seriously studied for its medicinal value.

It shows up in literature, poetry, art, and architectureearly in the twentieth century Spanish architect Antoni Gaud built a stylized garlic dome over an air vent on Barcelonas Casa Batll, perhaps his take on the more familiar onion dome of Spains Moorish history. Clay replicas of garlic or the real thing were buried with pharaohs and ancient kings to nourish and keep them safe from evil spirits as they passed into the great beyond. Images of garlic sometimes show up on hamsas, the hand-shaped amulets that protect against evil in the Middle East and North Africa. Garlic has appeared in paintingstwo examples are Diego Velsquezs A Young Woman Crushing Garlic and Vincent Van Goghs Still Life with Bloaters and Garlic and references to garlic abound in literature. Shakespeare often alluded to it, usually disparagingly, in his plays; Cervantes, in Don Quixote de la Mancha, was critical of the smell of garlic on Dulcineas breath; and one of Guy de Maupassants characters in The Rondoli Sisters is downright disgusted by people who carry about them the sickening smell of garlic. But in Mandalay, Rudyard Kipling speaks lyrically of garlic: You wont eed nothin else / But them spicy garlic smells, / An the sunshine an the palm-trees and the tinkly temple-bells; / on the road to Mandalay...

Garlic has also been used as currency. If Id been an Egyptian four thousand years ago with a sackful of garlic bulbs to barter, I could have bought a healthy slave to help me with my garden. That sounds like a better deal than paying the neighborhood teenagers twelve bucks an hour to pull weeds and prune the hedge. Garlic had intrinsic value, too: if Id been a stonemason working on a pyramid a millennium before that, Id have been issued garlic every day to keep me strong and disease free. A record of labor costs inscribed on the Great Pyramid of Cheops showed that sixteen thousand talents of silver was spent during one bookkeeping period to feed garlic, onions, and radishes to the thousands of pyramid builders. A talent was an ancient unit of mass, the amount of water that would fill an amphora, and it was also used to measure precious metals. Its impossible to compare ancient and modern measurements or monetary values, but if one Egyptian talent was equivalent to 80 Roman libra, or about 57 pounds (26 kilograms), as Pliny said a couple of millennia later, these three humble vegetables were worth a lot indeed.

But more than painting or writing about garlic, or buying slaves with it, humans have always liked to eat garlic, whether it was considered good for your health or not. The Mesopotamians, a civilized people who lived in what is now mainly Iraq four thousand years ago, enjoyed garlic with abandon. Forty recipes inscribed on three clay tablets from about 1900 BC (translated from the cuneiform in the 1980s by French scholar Jean Bottro and now part of Yale Universitys Babylonian Collection) use garlic and leeks liberally. The favorite technique was to mash and squeeze them through a cloth so that the juices were released into a pot of, say, mutton stew with beets and cumin. Garlics green tops didnt go to waste eitherthey were marinated in vinegar and used to garnish the bowl.

Dear actors, eat no onions or garlic, for we are to utter sweet breath.

BOTTOM in A Midsummer Nights Dream

AS THE centuries rolled by, garlics reputation as a health benefit didnt waver. Roman soldiers of the first centuries AD exuded clouds of garlic as they marched through Britannia and all the other countries they conquered, for they were issued several cloves of garlic a day to keep them strong and resistant to disease. Sailors plying the oceans reeked of garlic for the same reason. This belief in garlics value as preventive medicine lives on, possibly for good reason. At the first sign of a cold or a touch of grippe my eighty-something father-in-law chows down on a clove of garlic to keep the germs at bay. He swears it works, and hes not the only person in the world who believes that a fresh clove, a few drops of garlic oil, or a homeopathic capsule will fend off disease, cure a touch of catarrh or treat a toothache.

And we all know that garlic keeps us safe from vampires, those blood-sucking beings who terrorized the Balkans and other parts of the world for centuries before becoming a household word with the publication of Bram Stokers Dracula in 1897. Professor Van Helsing crushed garlic flowers on the windowsills and doors of Lucys room to keep the beast away, although judging by Francis Ford Coppolas 1992 movie version Lucy rather liked having him drop by at night.

Garlic has also come highly recommended as an aphrodisiac. In the first century AD Pliny the Elder wrote that to increase desire, garlic should be pounded with coriander and taken with neat wine. In the Talmud, Ezra, a priest-scribe in about 450 BC, decreed that Hebrew husbands just returned to Israel from exile in Babylon should eat garlic on Shabbat to help them fulfill their marital duties and repopulate their homeland.

BUT DESIRE isnt always desirable. Pliny also advised that garlic should be eaten during festivals of abstinence because its powerful aroma discouraged sexual activity. Celibates of every belief generally abstain from garlic for fear it will stimulate prohibited passions. In India, visitors with garlic breath are unwelcome in many places of pilgrimage and in some mosques and temples; yet garlic is an important ingredient in Indian cooking and has always been integral to Ayurvedic medicine.

Ah yes, theres always been a hint of ambivalence when it comes to garlic. A fourth-century Buddhist medical treatise written in Sanskrit on birch bark (the Bower Manuscript, so named for the Indian army lieutenant who found it in the nineteenth century) waxed poetic about the garlic plant with leaves dark blue like sapphires and bulbs white like jasmine, crystal, the white lotus, moonrays, or the conch shell, but the same manuscript also says that garlic sprang from the blood of a beheaded asura, a powerful being who was caught in the act of making off with the elixir of immortality. (A similar story with a Christian basis says garlic sprang from the footprint of Satan as he fled the Garden of Eden.) Even those garlic-loving Mesopotamians werent allowed to eat it on the first three days of the year, when favors were being asked of the gods. You never know when a bad smell is going to make a god mad.

Next page