The fireplace in the Housekeepers Room at Uppark, Sussex.

For my parents, Rae and David

First published in the United Kingdom in 2011 by

National Trust Books

10 Southcombe Street

London W14 0RA

An imprint of Anova Books Ltd

Copyright National Trust Books, 2011

Text Sin Evans, 2011

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

First eBook publication 2013

eBook ISBN: 978-1-90789-258-5

Also available in Hardback

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-90789-211-0

The print edition of this book can be ordered direct from the publisher at the website: www.anovabooks.com , or try your local bookshop. Also available at National Trust shops, including www.nationaltrustbooks.co.uk .

INTRODUCTION

No matter what our individual backgrounds, all our forebears either worked for other people, or had other people working for them. Statistically, our ancestors are more likely to have fetched and carried, cooked and cleaned for others, than to have issued instructions to servants.

In previous centuries in Britain, vast armies of people spent their working lives in domestic service: between 1700 and 1900, nearly 15 per cent of the working population were domestic servants. Some were dedicated and reliable, trusted members of the household. Others saw service as an opportunity to better themselves and acquire a useful trade in the homes of the wealthy. The majority of servants personal histories went largely unrecorded; before the advent of universal education in the 1870s, people from humble backgrounds would only have a rough working knowledge of their letters and numbers. They were kept occupied all day, with almost no free time, and had few opportunities to write detailed accounts of their lives.

However clues on paper survive. There are cellar books written by butlers, often in an increasingly spidery scrawl; house stewards records of wages paid, staff dismissed or replaced; blotted missives with idiosyncratic spelling from the housekeeper to inform the mistress that there are moths in the hangings, and terse four-fold notes to butlers from their masters, commanding urgent preparations for a royal visit. Down in the basement, a home remedy for gout has been laboriously transcribed into the cooks battered book of receipts.

Written and recorded accounts portray the everyday life in a great house. Those upstairs recall the sumptuous tea trays, the sparkling silver, the galaxy of candles lit and extinguished, night after night. The denizens of downstairs have more prosaic memories: the great hillocks of coal fed into the insatiable kitchen range, the heat, the steam, the smell of old cabbage and yellow soap, the black beetles, the misshapen shoes and worn corsets, the plate hands and the aching backs. Above all, they recall the need for absolute silence and invisibility once on the other side of the green baize door.

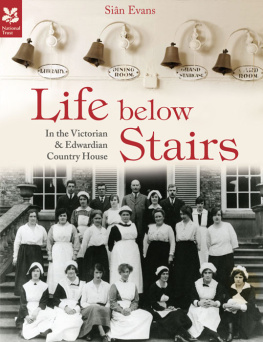

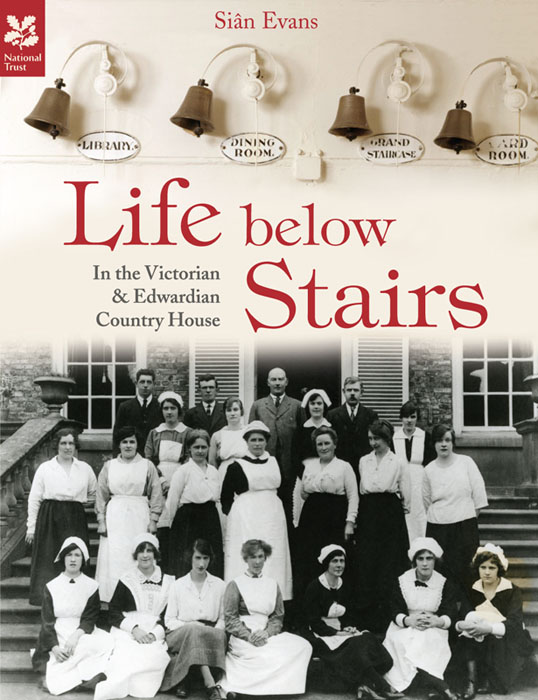

A group portrait of staff on the garden steps at Erddig in the early twentieth century. With cook at the centre and the male staff on the top step, photographs of servants from this era reveal the social pyramid of life below stairs.

There are forensic clues, too, in old houses: the uneven flagstones, worn by the footfall of boots; the texture of the enormous, ancient kitchen table, sanded down and scalded with hot water every morning for hundreds of years, leaving the grain exposed like the ridges of a beach at low tide; the metal fatigue in the wires that connect the bell-pull in the drawing room to the bellboard in the servants corridor.

This book examines the secret lives of servants, those who worked to sustain the aspirational lifestyles of the wealthy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The majority of these lives went unrecorded at the time, and the people who lived them are now largely forgotten. But, if we know where to look, there is a vast archive of material, from oral testimonies to handwritten notebooks, anarchic graffiti to printed Rules for Servants still hanging in servants halls, which can tell us much about the texture of everyday life below stairs.

O let us love our occupations,

Bless the squire and his relations,

Live upon our daily rations,

And always know our proper stations.

Charles Dickens, The Chimes, 1844

The Kitchen at Canons Ashby, with Victorian cast-iron range and cooking utensils and stone flagged floor. The row of bells governed all aspects of servants lives.

LIFE IN SERVICE

The idea that being a servant is somehow degrading or demeaning is comparatively recent. In the Middle Ages, society was feudal. Landowners had considerable power over their peasants, whose lives were dangerous, dirty and dependent upon the whims of their lord and the success of the next harvest. Joining an aristocrats household was an opportunity for social advancement. As a member of a noble family, a servant would be physically protected, have a better standard of living and gain higher social status.

There were three main routes to advancement: the Church, the Law or seeking a post in a great household. For the less spiritual or cerebral, service was an attractive option. Within each noble household, a hierarchy existed; the officer classes were often of higher birth and they acted as stewards or ushers, running the household and controlling the yeomen servants. In Britain, the nobility placed their offspring in other aristocratic households, once they were eight or nine years old, so that they could be taught social skills, manners and decorum. This system of farming out children to forge useful alliances and glean an education under anothers roof eventually evolved to become the English public-school system.

Every occupant of a great house owed a debt of loyalty and fealty to their lord. The medieval lord and master referred to his household as his family; landowners still sometimes refer to our people when talking of their tenants and staff. Medieval women servants worked as ladies maids, laundresses or nursemaids; all other duties, such as those of the cook, were performed by men. Partly this was an inevitable consequence of living in dangerous times: menservants doubled as bodyguards or soldiers, to repel raiding parties or to defend the households wealth.

At its peak, an important estate such as Knole in Kent required a huge army of servants, encompassing many trades and occupations. Maintaining a large household remained a status symbol throughout the Tudor era.

Great state was observed here once, when well over a hundred servants sat down daily to eat at long tables in the Great Hall all coming in from their bothies and outhouses to share in the communal meal with their master, his lady, their children, their guests, and the mob of indoor servants whose avocations ranged from His Lordships Favourite through innumerable pages, attendants, grooms and yeomen of various chambers, scriveners, pantry men, maids, clerks of the kitchen and the buttery