Life

Below Stairs

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2011

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publishers, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Papers used by Michael OMara Books Limited are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

ISBN: 978-1-84317-697-8 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-781-4 in EPub format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-782-1 in Mobipocket format

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Cover design by James Empringham

Designed and typeset by K DESIGN, Winscombe, Somerset

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

www.mombooks.com

In loving memory of my grandparents,

Jean and Sandy Cook and Jim and Dorothy Tripp.

With love and thanks to Sally and Gill.

Introduction

I N THE TWENTY-FIRST century, domestic service is the domain of the few butlers, housekeepers and nannies who keep the richest homes in the country ticking over and usually command a high wage. But just one hundred years ago, service was the largest form of employment in the UK. The 1911 census showed that 1.3 million people in England and Wales worked below stairs and many of those would have been in average middle-class homes, employed by doctors, lawyers and office clerks, rather than dukes and princes.

With millions of families living in stifling poverty in the Edwardian era, going into service was a sought-after alternative to near starvation but it was no easy option. From scullery maid to housekeeper and butler, the domestic servant was at the beck and call of their master and mistress every hour of the day. Up with the lark and toiling well into the night, they were rewarded with meagre wages and sparse, comfort-free accommodation in the attic or basement. While their employers dined on nine-course meals, costing up to six times a maids annual wage, employees were treated to the leftover cold cuts in the basement kitchen. As the Edwardian upper classes organized their busy social calendars around the London season, the shooting season and weekend parties, the staff was lucky to get one day off a month.

But even as the more fortunate Edwardians basked in the lap of luxury, the winds of change were beginning to blow. Opportunities in shops, manufacturing and offices were offering young girls higher wages and more free time, the suffragette movement was filling the newspapers, and the lower classes, who once knew their place, were beginning to demand more from their middle- and upper-class employers. The servant problem was a frequent topic of conversation in society drawing rooms and politicians anxiously discussed what could be done to encourage more workers to choose domestic service. In 1914, the First World War saw the end of the golden age of domestic service. Life Below Stairs was soon to become a thing of the past.

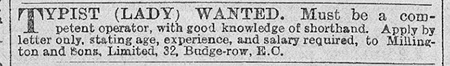

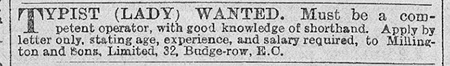

Domestic service was not the only option for young women

CHAPTER ONE

Social

Background

D URING THE CLASS-RIDDEN Victorian era, the social divide between rich and poor had become a chasm. By the turn of the century, poverty had reached shocking levels, especially in cities, and in his 1901 report on the slums of York the Quaker philanthropist Seebohm Rowntree concluded that 28 per cent of the population of the city was living in intolerable hardship. At the same time he concluded that the keeping of or not keeping of servants was the defining line between the working classes and those of a superior social standing.

Domestic service, while arduous and all-consuming, provided a reasonable alternative to the slums and a certain amount of social status, and was taken up by a significant number of both sexes in Britain. A large percentage of women who worked were in service. The 1901 census showed that they numbered 1,690,686 women, or 40.5 per cent of the adult female working population.

Children, particularly girls, also made up a significant proportion of the lower posts in a large household and the higher up the social scale the employer, the more cachet was awarded to the positions in the house. Young girls would be looking for a post in a good home from the age of twelve or thirteen, and in some cases they started as young as ten. And while many of these came from the city slums, employers often preferred to take the children of rural families, who were considered to be more conscientious and hard-working than those from the cities.

Work was hard but maids were an essential addition to all homes from the lower middle classes upwards. In an age of few labour-saving appliances, the mistress of the house would struggle to run even an average-sized household on her own. An aristocratic seat or country house would require a large staff in order to run from day to day, while even a modest middle-class home would employ one or two servants.

At the turn of the century, however, things were beginning to change, at least for the professional classes. In his 1904 publication The English House, German architect Hermann Muthesius said that many middle-class families complained that, with new opportunities for working women in shops and offices, 20 maids, those who earned around 20 annually, were hard to come by. That, along with the introduction of household appliances over the coming years, led to a decline in domestic staff and a rethink of the architecture of middle-income homes. Houses became smaller, cosier and more manageable for a housewife and, after the First World War, staff were to be found in the wealthier households alone.

In the years leading up to the war, a familys social standing was heavily dependent on the number of staff it could afford to employ, as this was an obvious indication of wealth. Many of the richer families would employ up to twenty staff and, in the larger aristocratic homes, it often increased to thirty or forty. At the Duke of Westminsters country seat, Eaton Hall in Cheshire, there were over three hundred servants, although this was an exceptionally large number, even amongst the aristocracy.

Next page