To Emma and Peregrine,

my fellow travellers on this extraordinary journey.

CONTENTS

Guide

NOTE: The grey highlighted sections indicate text which was cut from the original script to make the final edited version.

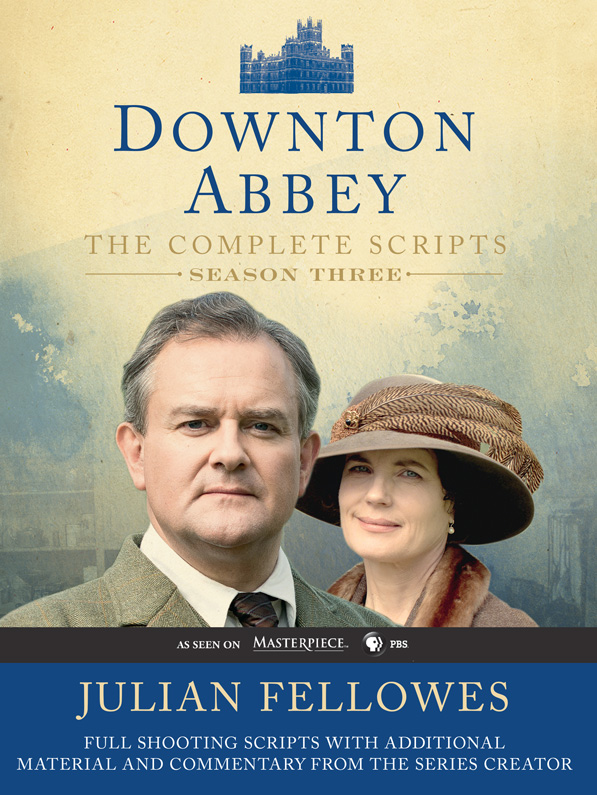

At the end of the second series, we left our characters facing the new decade and the new postwar world. Matthew may have (finally) proposed, but little else was settled about the future of the Crawley family. As a matter of fact, I have always been interested in the 1920s, and now we were finally there. It strikes me as a curious, almost nebulous, time, an impression that was strengthened by the accounts of my great-aunts, whom I knew well as a young man and who had vivid memories of the era. My eldest great-aunt, Isie, had been born in 1880 and so this was the decade of her forties. Her husband had died of wounds in the last days of the war and, with an infant son, she had essentially to negotiate those years alone. According to her, at the very beginning nobody was quite sure what had really changed, and what would go back to the way it had been before the war. As time went on, it became increasingly clear that fundamental change had occurred and nothing would ever be the same again, but it took a little while for this to sink in, and it was that very uncertainty that attracted me to the period as a background to a family drama.

There were milestones, markers, along the way. When Lloyd George suddenly ended agricultural relief, without warning, in 1922, he struck a blow against the landowners, many of whom had been in debt since the agricultural depression of the last decades of the nineteenth century, and had taken out loans and mortgages, thinking and hoping, Micawber-like, that something would turn up. But of course for the majority nothing turned up. There was also an anomaly, which I am sure was deliberate, that selling land was still regarded as a capital gain, on which, in those days, there was no tax. So your option was either to lumber on with an erratic farming income, subject to heavy income tax, or to cash in your chips for a tax-free lump sum. Inevitably, and I believe as Lloyd George intended, something like a third of England was sold between the wars.

Counterbalancing that, and creating the baffling illusion of continuity, the new rich and there were many continued to spend their fortunes in the old way. I dont mean these were war profiteers in a pejorative sense, but wars do certainly make fortunes and, besides them, there were industrialists and manufacturers and, perhaps most prominently in this company, the powerful newspaper magnates, all of whom aped the Victorian model and purchased great houses and great estates on which to lavish their newly gotten gains. So, there was this slightly bewildering contradiction of old families going under all over the place, but huge palaces, in the ownership of Lord Rothermere or Lord Beaverbrook and their kind, being run with an extravagance scarcely seen since the 1890s.

Being rich in a new way was something being developed by the Americans, and it would not really reach these shores until after the Second World War. The Americans never felt the European imperative to separate themselves from the source of their money, and would cheerfully go into the bank or the office every morning, long after they had taken the reins of New York Society. They had their palaces, too, of course, at Newport or on Long Island, but they felt no need to imitate farmers with profitless estates. Their model is much more recognisable to the present generation when, now, riches are more likely to be devoted to helicopters, Manhattan apartments and houses in the South of France than to the purchase of 20,000 acres of the North Riding. But in the 1920s you had this strange contrast: the new rich creating the illusion that the old way of life would continue, while many of the old rich were chucking in the towel.

Then this was also an era of tremendous social change, not just because of organised labour or womens rights or the rise of the Labour Party, but also because of the cinema and sports cars and aeroplanes and all the other tell-tale signs of the fast-moving twentieth century. My own Great-Uncle Peregrine was a Commodore in the Navy, a man as straight as a ruled line who found himself unable to resist the fascination of flight. By the end of the war he had become a pioneer flyer in the Royal Naval Air Service, and afterwards he became one of the first Air Equerries to King George V. Later, in 1933, he would lead the Houston Everest Flight when they flew over Everest in an effort to win public support for government investment in air power, because Germany was so far ahead in the race one of the many steps that led to the second war and ultimately to the modern world. His journey, from a country Victorian boyhood to fighting a deadly air battle with the Nazis, gives some impression of the speed of change that generation had to live through.

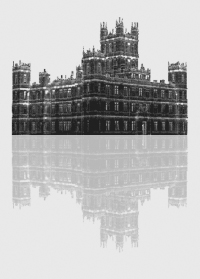

That was the 1920s, the bridge between the old world and the new, and that is what we explore in this, the third series of Downton Abbey.

Julian Fellowes

ACT ONE

1A EXT. CHURCH. DOWNTON VILLAGE. DAY.

Daisy pushes a bicycle towards the church.

1B INT. CHURCH. DOWNTON VILLAGE. DAY.

At first this seems to be a simple wedding, with the young couple in day dress and only a few guests sitting in the front pews. Then the sheet tucked into the brides belt and the three mothers fussing with the four little bridesmaids and the general murmur all round tell us it is only a rehearsal. An immensely important prelate stands by the altar, while Mr Travis fusses about. Mary turns to the first little girl behind her.

MARY: Are you going to be as naughty as this on the day?

BRIDESMAID: Im going to be a great deal naughtier.

Mary raises her eyebrows to a hovering mother.

MOTHER: No, she isnt. Arabella, why do you say such things?

Matthew whispers to Mary.

MATTHEW: I bet she is.

They laugh.

MATTHEW (CONTD): Is there any news of Sybil?

MARY: Shes still not coming. She insists they cant afford it.

MATTHEW: Thats Branson talking.

ARCHBISHOP OF YORK: Mr Travis? Can we move forward?

The Reverend Mr Travis is getting increasingly flustered.

TRAVIS: If I could just ask you to come down the aisle again? Can we get the troops organised?

The mothers and children shuffle to the door of the church. Now we see Robert, Cora and Edith in the front row.

ROBERT: That means me.

CORA: It seems rather hard on poor old Travis when hes doing all the work but the Archbishop gets the glory. Well have to ask him to dine.

Robert stands to walk with Mary to the starting place. But the pair of them remain for a moment with the others.

MARY: Papa was the one who wanted a Prince of the Church. I would have settled for Travis.

They move off.

MARY (CONTD): Is there really no way to get Sybil over? It seems ridiculous.

ROBERT: On the contrary; its a relief. Branson is still an object of fascination for the county. Well ask him here when we can prepare the servants and manage it gently.