Contents

Guide

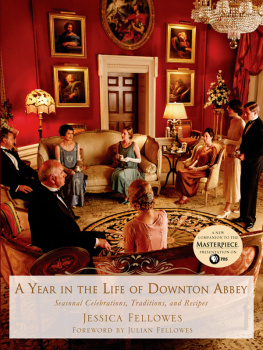

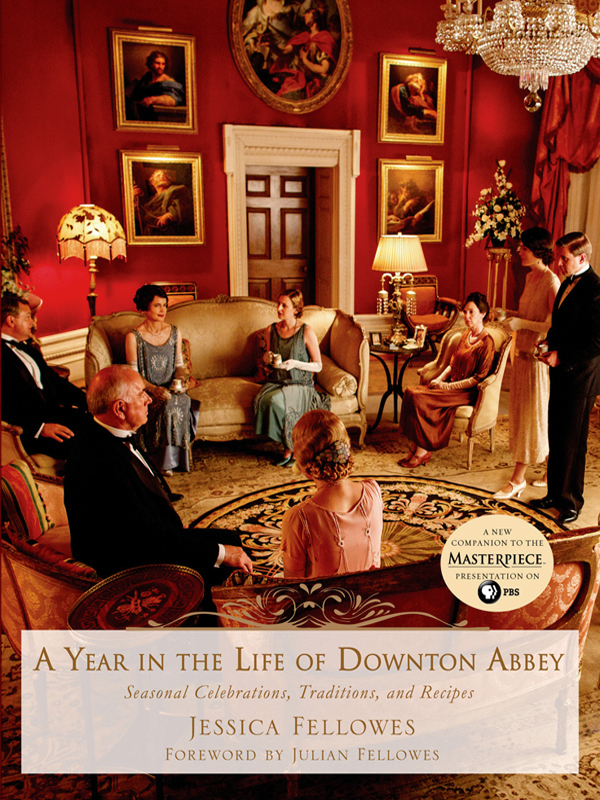

A Y EAR I N T HE L IFE O F D OWNTON A BBEY

B Y J ESSICA F ELLOWES

F OREWORD BY J ULIAN F ELLOWES

A C ARNIVAL F ILMS /

M ASTERPIECE C O-PRODUCTION

P HOTOGRAPHY

N ICK B RIGGS

S T. M ARTINS P RESS

N EW Y ORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Julian Fellowes

FOREWORD

It seems strange to think that we have completed the fifth series of Downton Abbey, that we have taken these people through twelve years of change, through a war from which they emerged into a very different world, through all the emotional hiccoughs that are part of the human journey, much of which will be examined in this, the fourth book of the show. I like the idea of recording the Downton year. It seems a good device to me, since there is no question that life for the people who lived in these houses, their activities, their clothes, the very food they ate, was entirely dominated by the rhythm of the changing seasons. That has almost gone now. Central heating, imported produce, the abolition of formality, have collaborated to achieve a kind of twelve-month sameness. You see summer dresses at a New Years Eve party and most of us have lost all connection with when vegetables and fruit are ripe for eating, because when they are not, the gap is supplied from abroad.

But like so many other aspects of life that we have shown, as we trace the trials and tribulations of the Crawley family and their dependants, this was different until very recently. In my own childhood and early teenage years, we lived in a house in Sussex, and my mother would arrive from London, usually on Friday morning (she would drive down after she had seen my father carried away to his male world), and the gardener would have laid out a selection of vegetables that were ready. The system had its drawbacks. You would eat broccoli or cabbage or Brussels sprouts, each in their own true season, until they were coming out of your ears, but yet, even then, when we thought nothing of such things, there was a kind of comforting rightness to it that artichokes from the Sudan or blueberries from Chad cannot quite match.

I remember very well the day things changed. I must have been about sixteen. My father finally sat down and worked out that every potato was costing him about twenty times more than if it were bought in a shop and he announced at dinner that the kitchen garden was to go. My mother was rather sad and managed to save the peach wall and some strawberry beds under netting, but before long the rest was history. They dug a rather inefficient (and freezing) swimming pool in one corner of the walled garden, and the rest supplied us with a badminton court and a place where all the Christmas trees from then on were planted. This was before the modern habit of removing their roots. I liked the Christmas grove, where the trees had grown quite big before the house was sold a quarter of a century later, and I didnt mind the court, or even the deficient pool, although I seldom swam, but there was something that had gone from our annual round and I suppose that, like so much else in the self-consciously changing world of the 1960s, it was because we were less connected to the soil than we had been.

As Jessica shows in this book, sports were a huge determinant of the annual round among the Crawleys and their kind, more perhaps before the war than ever again. There were many men, my own grandfather included, who didnt seem to do anything but sport, certainly not with any real interest. Shooting began in August, with grouse in the north, then came partridges, followed by pheasant, which ended, then as now, on 1 February (not, as I have seen printed many times, on 31 January). Shooting parties suited the constrictions of the late Victorians as they offered an opportunity for people to meet and flirt and generally get to know each other when they were not related, but at the same time, shooting seemed to give a purpose to a house party to mask the real reason, romantic or ambitious, for the introductions. Other sports, like fishing and sailing, tended to draw in the enthusiasts, but they did not have the wide appeal of shooting, which more or less every man of a certain type was expected to be able to do whether or not he was particularly good at it. Even hunting was restricted to a smaller group, although, after shooting, it was definitely the most social sport. Years later Evelyn Waugh, who was a keen follower of hounds for many years, admitted that his reasons for supporting the hunt were completely social. Certainly the hunting set in most counties could never have been accused of not smiling on flirtations of all sorts.

Cricket had a role in a country-house summer. More than any other sport practised by the occupants of the great houses, it had the potential to draw the different elements of the community into a single challenge, and there were many examples of the House playing the Village, or the Estate Workers playing the House, and so on. Cricket is hard to explain to those who are not keen, and I am not a sportsman in any case, but even I can remember the matches of village cricket in my youth with nostalgic affection. There is something about the sound of that soft rather lazy ripple of applause, as a community sprawls around a local game, making daisy chains and eyeing the tea tent, that is more evocative of the English summer than almost anything.

Sometimes people took the opportunity, after shooting and hunting were done, for travel in warmer climes, but by the spring the London Season was really under way, its first official date the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. It would continue, at a hectic pace, until the end of June, and there would follow sojourns in the country, when cricket would have its moment, but it wasnt long before it was time to go north and start killing things again.

We have taken these people through twelve years of change

I think clothes were the final defining element of the fashionable year. Now, people cheerfully wear much the same things from January to December without a lot of variation. Lighter suits for men when the weather gets warm, a few more floaty dresses for women when the sun is really beating down, although, as I have said, you will still see them when the leaves are off the trees. But then, there were four wardrobes for a well-dressed woman, spring, summer, autumn and winter and this never varied. This was the heyday of the great fashion houses. They had been going since Charles Frederick Worth opened his own shop, Maison Worth, in 1858, conquering the Second Empire in the process, but I think it was between the wars and for a decade or so after that the rule or tyranny of the fashion leaders held mightiest sway. In the series, we mention Patou and Lucile and Molyneux and various others, and all these designers had their followings. Lucile was glamorous but safe, Patou more daring, Molyneux definitively chic, and so on. Every woman, even those far from the catchment of these great stars, would follow their lead and assemble different wardrobes for the seasons. Even my own mother, who certainly had no money or not what she would have called real money would go on four modest buying sprees a year, usually blaming the expenditure on the sartorial demands of our schools Summer Exhibition, viz. the headmasters dinner, the garden party at our prep school, High Mass, etc., when my father questioned her. But she continued the practice after the last of us had left. Today, some women do much the same of course and good luck to them, but for most of the population, the sub-division of a wardrobe into seasons seems to have subsided or vanished altogether.