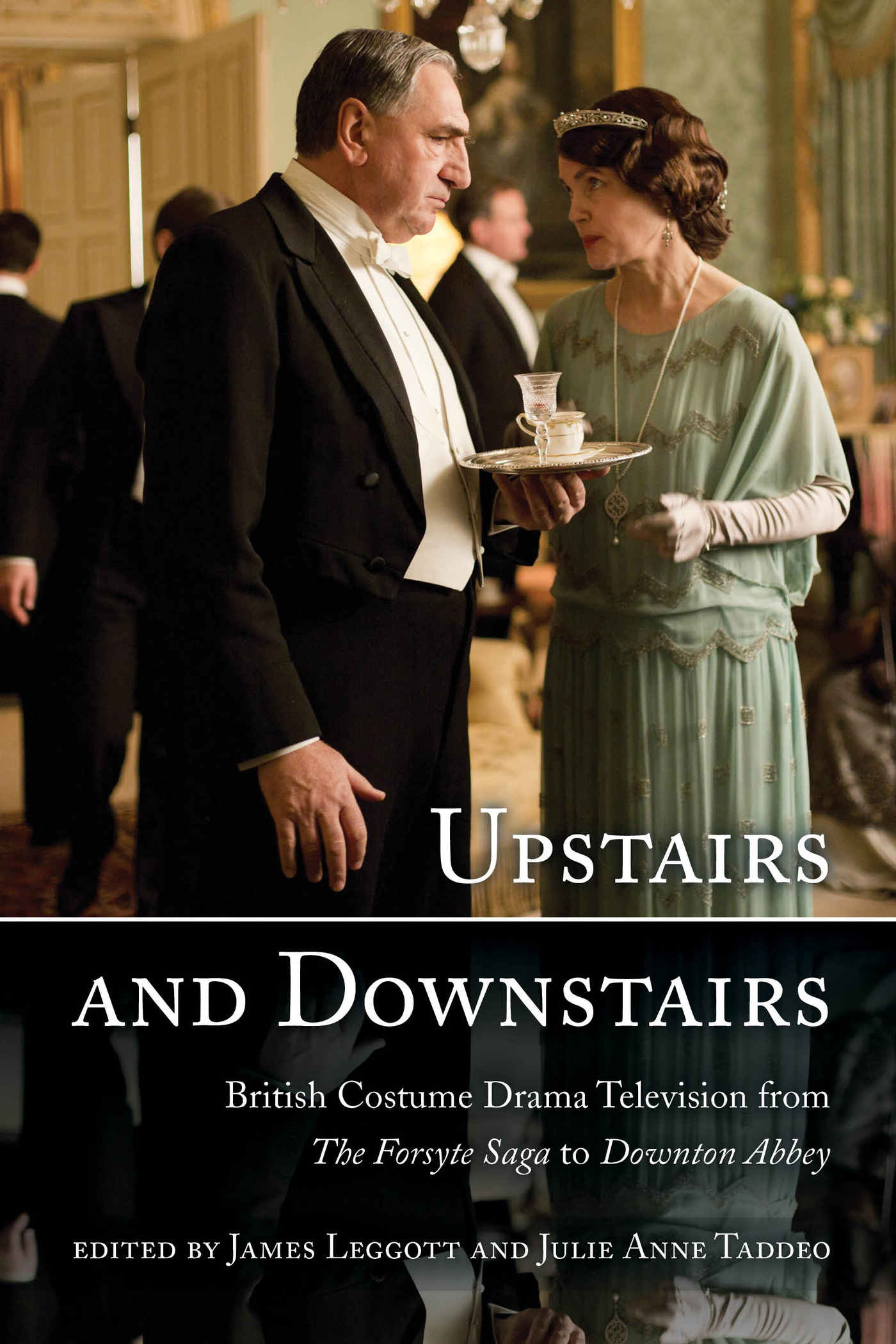

Upstairs and Downstairs

British Costume Drama Television from

The Forsyte Saga to Downton Abbey

Edited by

James Leggott

Julie Anne Taddeo

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Upstairs and downstairs : British costume drama television from The Forsyte saga to Downton Abbey / edited by James Leggott, Julie Anne Taddeo.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-4482-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-4483-2 (ebook)

1. Historical television programsGreat BritainHistory and criticism. 2. Clothing and dress on television. 3. Television seriesGreat Britain. I. Leggott, James, editor. II. Taddeo, Julie Anne, editor.

PN1992.8.H56U68 2015

791.45'65841dc23

2014031795

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Foreword

Jerome de Groot

In an acid comment upon the heritage process, James Bond destroys his country home in Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012) as a way of becoming un-British, an international postmodern orphan, and therefore the perfect assassin. He leaves the period-drama setting for pastures new, spectacularly severing ties with the old country. It slows him down. Maybe the costume drama is a form that expresses something we want, really, to destroy: the heritage-lite of remembered Sunday evenings. We dont really want to revisit too much but are compelled to do so. As the Bond episode suggests, there is an argument that costume drama is the most British of all television genres. It is certainly one of the most exported. While other countries developed and sustained excellent television in other exciting areas, the costume drama has been regularly on British screens in various manifestations for decades. It has had regular moments of renaissance, from The Forsyte Saga (BBC, 1967) and Brideshead Revisited (Granada, 1981) to Pride and Prejudice (BBC, 1995) and Downton Abbey (ITV, 2010 ). It intertwines with British national identity in multiple complex and subtle ways, from the adaptation of great national writers (Dickens, Bront, and Austen) to the use of the landscapes and houses throughout the country as backdrops and locations. Regardless of whether we agree with the version of Britishness that is being presented, it is inarguably important and influential.

Furthermore, British costume drama is used to present a particular sense of this British identity throughout the world. The Forsyte Sagaan epic twenty-six episodeswas made in conjunction with MGM television and was the first BBC show to be sold to the USSR; recently, the chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, has sparked controversy by hoping that the huge number of Chinese viewers of Downton Abbey might translate into a boost for the UK tourist economy. Costume drama intertwines with heritage; it is part of a peculiarly British vernacular that has international impact. Shows are developed with an eye to the export market and form part of a complex fiction-heritage aesthetic that contributes a great deal to the domestic economy. A good example of how this itself has become part of the cultural imagination is seen in the film Austenland (Jerusha Hess, 2013), in which an impressionable American fan spends her life savings traveling to the immersive theme park Austenland in the UK. It is clear that the Austen she and her fellow tourists are chasing is largely that created by serial adaptation (basically, Colin Firth).

Throughout the 1980s the unstoppable rise of period drama seemed inarguable. This was mainly through the huge success of certain films, and the relationship between British film industry and British television industry in this area needs further investigation. Suddenly a particular kind of Britishness was being articulated, and a way of considering oneself in relation to the past came into vogue. Costume drama became almost fashionable, certainly a key way of conceptualizing contemporary identity. This is well satirized in Alan Hollinghursts novel about the conservative 1980s, The Line of Beauty:

Martine slightly surprised him by saying, I think its so boring now, everything takes part in the past.

Oh... I see. You mean all these costume dramas...

Costume dramas. All of this period stuff. Dont the English actors get fed up with itthey are all the time in evening dress.

Period stuff is so regular as to be worthy of complaining about, something so very 1980s that it would form part of the background of a historical novel. Hollinghursts exquisite joke is that the protagonist Nick and his lover are planning a version of Henry Jamess Spoils of Poynton. The suggestion is that this adaptation comes nowhere near the original; indeed, even attempting it is a kind of joke on the vulgar culture that might allow or demand such a thing.

Costume drama during the 1980s became something that would export British values of some kind around the world and suggest something about the way that British culture conceptualized itself historiographically. Scholarship took on the rise in heritage/costume drama, and a number of key interventions were made in the 1980s and early 1990s by writers such as Patrick Wright, Andrew Higson, Alison Light, David Lowenthal, Robert Hewison, and Raphael Samuel. They intervened regarding what Samuel termed Thatcherism in period dress. Costume drama, they recognized, is never just a genre but always a site of contention about memory, national identity, and nostalgia. It is produced by a set of cultural institutions (e.g., Granada, ITV, and BBC) with their own agendas, by writers (Andrew Davies, Julian Fellowes, etc.) with particular biases, and for a set of markets (e.g., Sunday teatime, American Masterpiece presentation, and Chinese export) with particular tastes and desires. Costume drama presents us with a serious canon of fictional production of the past. Often dismissed as something trite, conservative, and dull, costume drama demonstrates to us throughout its history the multiple ways that television might dramatize and enact relationships between the past and the present, illustrate a way of conceptualizing and idealizing the past, and resource the contemporary historical imagination.

The intervention of Davies into the classical adaptation must be appreciated here, in shifting (from 1995 onward) the focus of the form. In a similar fashion, the massive worldwide success of Fellowess Downton Abbey will warp and shift the landscape of future production in a way that we cannot at present fathom. Certainly after

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.