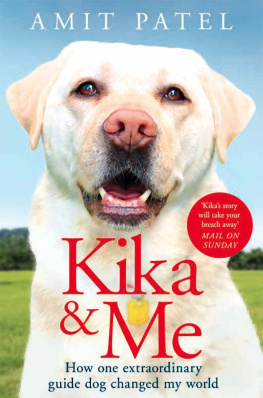

Kika & Me

Dr Amit Patel is a disability rights campaigner, fundraiser, motivational speaker and independent diversity and accessibility consultant. He studied medicine at Cambridge University and qualified as a doctor, specializing in emergency medicine and major incidents. During medical school Amit was diagnosed with keratoconus, an eye condition that is usually easily treated with a corneal transplant. However, he was one of the rare individuals for whom the transplants rejected and he was registered severely sight impaired (blind) in 2013, just one year after getting married. After coming to terms with his own sight loss, Amit set out to help others who were new to sight loss, through volunteering with the Royal National Institute of Blind People and the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association. Amit is married to Seema and they have two children. Kika & Me is his first book.

Kika is a white Labrador who has been matched to Amit since September 2015.

You can follow Amit and Kikas adventures on Twitter @BlindDad_Uk and @Kika_GuideDog, and on Instagram @kika_guidedog.

Dr Amit Patel

with Chris Manby

Kika & Me

How one extraordinary guide dog changed my world

To my beautiful wife Seema: without your belief in us I would have never found my way when the lights suddenly went out.

To Kika, Abhishek and Anoushka:

Im a better person because of you.

Contents

Prologue

Rush hour on the London Underground is not for the fainthearted. As thousands of people descend on the busiest stations at the end of the working day, its easy to feel intimidated by the crush of humanity intent on getting home, just as I was one winter afternoon in 2014. But making it even more overwhelming for me was the fact that, just a year earlier, I had lost my sight.

It had been a long day. In the morning, Id set out towards central London with a tentative spring in my step to attend a Living with Sight Loss course at the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). Id recently learned to use a white cane and I knew the journey well. After a slight mishap on my first trip, Id memorized the route with precision. I knew exactly where I needed to be on the Tube to make sure I got out at the right end of the platform at Kings Cross and found the steps that would take me to the exit closest to the RNIB offices.

Though it was a journey Id done several times by this point, I still found getting from A to B with my white cane tiring. Arriving in the room where the course took place, I would collapse into a chair and gratefully accept the offer of a coffee. I always needed it. All the people Id met on the course so far felt the same way when they arrived. There was great camaraderie in our shared stories of the trials of travelling across the city while blind.

Because the journey to the RNIB took so much out of me, I was careful to minimize the potential for problems on the way home. That meant I usually left the office when the Tube was least likely to be busy. Id worked out that I needed to be on my way before three oclock, which marked kick-out time for the kids at the local secondary schools.

But on that particular day, I did not leave the office before three. I enjoyed being at the RNIB, talking to people who knew what it was like to navigate a world without sight. It was a real relief to be able to chat about the ups and downs of my life, knowing that my new friends understood every single thing I was saying. I dont remember what we were talking about on that occasion, but it was interesting enough to make me decide that it wouldnt hurt to hang on for a little longer than usual. I was reluctant to bring the conversation to a close.

Eventually, the group began to break up and we went our separate ways. I said a cheerful goodbye to my friends and the course leader and headed for Kings Cross. I retraced the steps Id made that morning, crossed the big main road, found the right entrance to the station and took the escalator down to the Tube. I wondered as I did so whether I would ever really get used to travelling on the Underground again. Working as an A&E doctor near Kings Cross before I lost my sight, my daily journey to and from work had held very few surprises, but without sight the Underground was a different world.

That winter day I had misjudged my departure time badly, getting to the station at the moment when the school run met the beginning of rush hour proper. The tunnels down to the platform echoed with the voices of excited teenagers, playing out their little dramas at full volume.

Ordinarily, on getting to the platform, I would have stayed close to the spot where I entered, knowing that I would be in line with a train door when the Tube came in. That day it was too busy to stand where I wanted to. People were pouring down the escalator behind me and I was jostled and shoved as they tried to squeeze onto the platform. I hated being knocked into so I decided I would move along to try to find just a little more room. Getting through the crowd was hard work. Once London commuters have found their spot, they stick to it. Absorbed in their phones and their newspapers, they probably didnt even notice my cane. But I persevered and after a while the crowd did thin out. I felt a little easier. I breathed deeply and tried to relax. I hoped I wouldnt have to wait too long. There had been no announcement of a delay.

An underground tunnel is an echo chamber to me. The shape of the walls and the ceramic tiles bounce noise all around. It wasnt something I noticed when I could still see, but now the soundscape was so much more important to me, I found it difficult to ignore the cacophony. Unable to tell where noises were coming from because of all the conflicting echoes, I didnt hear him approaching me.

The first thing I knew was that someone had grabbed me by the tops of my arms. What was going on? Were they trying to stop me from getting too close to the platform edge? Were they trying to help? No. That wasnt it. They werent pulling me back they were turning me around. I guessed from the height and the strength that the person holding me was male. Young. Strong. He turned me easily, though when he spoke I realized he could only be a teenager.

He spun me round and round and then he said, with a confident sneer in his voice, Lets see if you can find your way now.

Then he let go of my arms and just carried on down the platform. In his wake went more teens, both male and female, laughing at his daring, congratulating him on his great joke. But it was no joke to me.

Moments earlier, Id been waiting calmly for my train. Being on such a busy platform wasnt ideal but at least Id known roughly where I was. Id estimated that I was a good distance from the edge, with my back to the tunnel wall, facing the train tracks. The safest position. Now I had no idea where I was at all.

I felt right then as though I was absolutely alone on that platform. I could hear only the sound of my blood in my head as a sense of panic began to engulf me. I could not move. I didnt dare. It was too dangerous. If I stepped in the wrong direction, towards the tracks, I could be stepping straight into oblivion.

Had no one else seen what had happened? Nobody was coming to my aid. I would have asked for help but my voice had frozen in my throat and I could only croak. I felt the prickle of shame and embarrassment behind my eyes and beneath my armpits as I grew hotter and hotter and came close to tears.

In the middle of rush hour at one of Londons busiest stations, surrounded by my fellow commuters, I felt like I was on my own in hell. Id been pranked by a bunch of kids but their joke, which would be forgotten by the time they were home, had left me fearing for my life, literally not knowing where to turn as the next train thundered down the track.