Preface : B. B.s Dreams

Riley B. B. King was born on a cotton plantation near Indianola, Mississippi, in 1925. As a child in the Mississippi Delta, Jim Crows ground zero, he labored as a sharecropper, as did nearly everyone he knew. King was restless, however, and soon the backbreaking labor that he and his family endured in those cotton fields, combined with the call of Memphiss bright lights, became too much for young B. B. to bear. Eventually, he found a way out, one built of six strings, wood, magnets, and wire; when he plugged it in, it burst with howls and despair that sounded far beyond his years. Eventually it, and the other guitars he would play for the rest of his life, would be named Lucille.

B. B. King was famous and loved, winning presidential honors and industry awards. But at his heart, he was a troubadour, always ready to travel with Lucille in hand. He lived for the music until it inevitably outlived his body. His vision, his life, teemed with the stuff of American history, the good and the bad, that shaped his twentieth-century world.

As a child, King sopped up the sounds around him like a sponge, twisting up all of these musical ideas in his head, and then cascading new sounds through his fingers as they worked the fretboard. His Mississippi Delta was not a land of isolation; he did not rehearse ancient field hollers from the days of slavery. And while he sang in the Baptist church, old time spirituals, ultimately, were not his game. He had radio. He could tune in the latest pop gems blanketing the countryside from New York City ballroom broadcasts; he could follow all the hit parades and keep up with the jazz kings and queens. Or, like he often did on Saturday nights, he could dial into the Grand Ole Opry on Nashvilles WSM .

Yet through all of the sounds that competed for his imagination, one seemed to triumph above the rest. As he recounted it, it fundamentally shaped his sound as a bluesman. It was that sound of the Hawaiian steel guitar. Well, Id hear it on the radio, he told National Public Radios Terry Gross in 1995. I would hear the Hawaiian sound or the country music players play steel and slide guitars, if you will. And I hear thatto me a steel guitar is one of the sweetest sounds this side of heaven. I still like it, and that was one of the things that I tried to do so much, was to imitate that that sound! I could never get it, I still have not been able to do it, [but] that was the beginning of the trill on my hand.

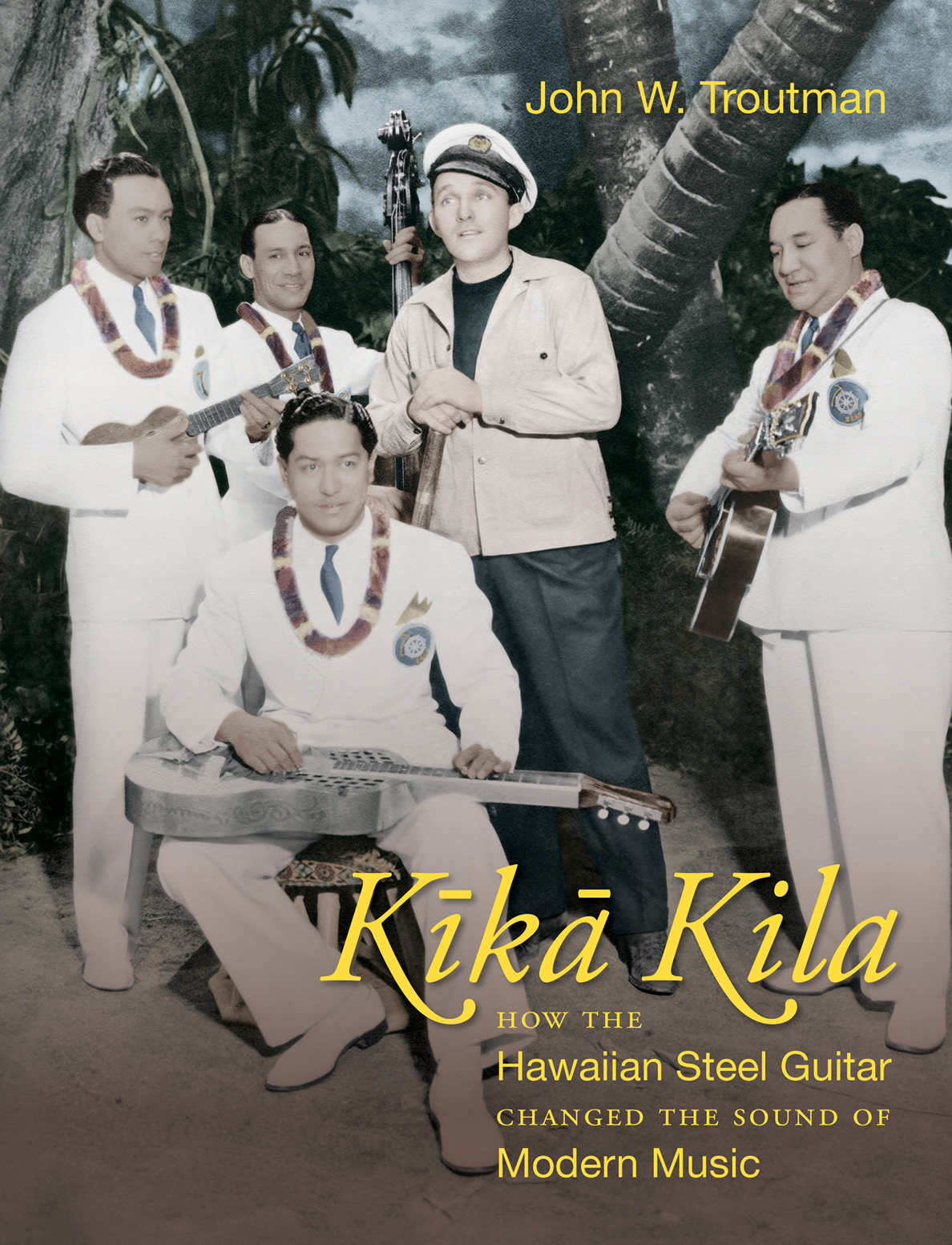

This book reveals the journey of the steel guitar, from its birth within the stunning guitar culture of late nineteenth-century Hawaii, to its haunting the dreams of B. B. King and others, to its disappearance, and return, in its Hawaiian homelands. It places an instrument at the center of the story, and follows its travels and players around the world. It is a story of modern innovation and global proliferation, hidden and obscured over time. Above all, it is a story of how a Native Hawaiian instrument changed the sound of the world.

It is also a story close to my heart, as I have played the steel guitar for nearly half my life. During that time, Ive played the instrument in some unusual placesfrom a dance hall in the middle of the Atchafalaya Swamp to grand English theatres; from a bowling alley in New Orleans to a film festival on the French Riviera. Once I played steel guitar at a comic book convention jammed inside a nondescript warehouse in Athens, Greece, surrounded by packs of roving dogs. The instrument seems unbounded by contexts; it creates a familiar sound in all of them.

The road stories that spring from such experiences are the stuff of life for working musicians. They eclipse the boredom imbedded in long days on the road, or in the hours of downtime between sound check and showtime. Musicians have told these stories ever since they first discovered that they could get paid to play. But what first led me to this book was my realization that a little-known indigenous technology centers in each of these stories, these gigs. A Kanaka Maolia Hawaiianinstrument. Today the sound of the steel guitar is everywhere, it is practically impossible to avoid, no matter your musical preferences. So then why do this instrument and its origins seem so hidden from view? What can we learn from its travels, and where did it come from, anyway?

Though it has been called into the service of the blues, country, rock, and countless other genres, the steel guitar was originally built to better serve the melodies composed by Hawaiis sovereigns. It fortified a Hawaiian culture then under attack by land-hungry hole (foreigners) plotting to overthrow the kingdom. It soon spawned a yearning for Hawaiian music of unprecedented, global proportion, while it sparked musical revolutions in the United States. By the 1970s, however, it came to be shunned in some parts of the Islands, its sound equated with cultural loss rather than rebirth. It is an instrument with a heavy history. The instrument has endured a challenged and storied, yet remarkably adaptable existence. It has changed how we hear, and expect to hear, music throughout the world. The Hawaiian steel guitar demonstrates how the past is profoundly implicated in musical performance.

As I thought about writing this book, I wondered how I might stitch together the instruments vast and unruly history. The instrument humbled me as I began to learn of its origins, and the many traditions that it has inspired. Likewise, the reach of the instrument is far more expansive than I originally imagined. As a consequence, the book took me on what became an eight-year research odyssey, from the Hawaii State Archives to the British Library, from family reminiscences in Waimnalo to a luau under florescent lights inside a Holiday Inn in Joliet, Illinois. At each stop, a new history of modern music unfolded before me.