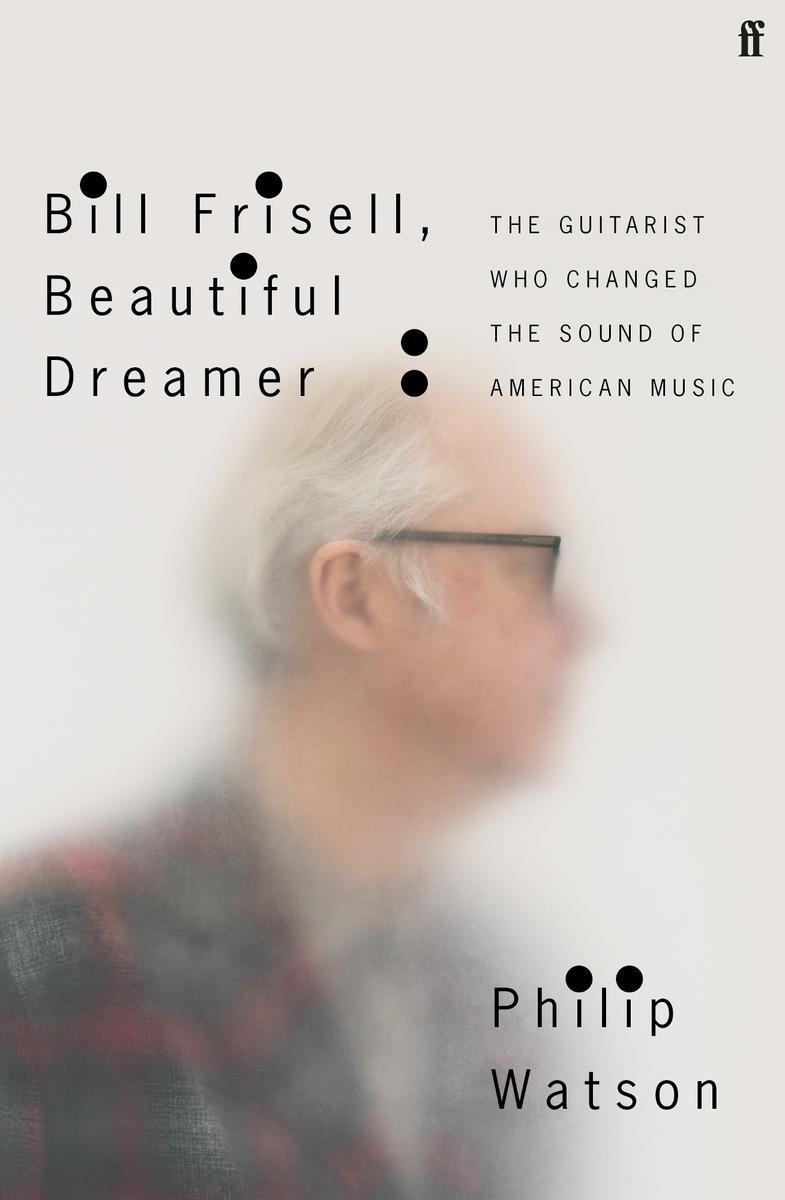

Bill Frisell has a dream. Its a real dream, one that he had thirty years ago now but that has stayed with him. A dream that occasionally comes back to him during waking hours, yet only partially, mutably, like a sequence of fading and distorting Polaroids.

In it, Frisell enters a large mansion and climbs a series of winding stairs that take him higher and higher. The building is rambling, ornate, American Gothic; it is dark and shadowy, and feels strangely claustrophobic.

At the top of the house, at the end of a long wood-panelled corridor, he scales a ladder that leads him up, through a gap in the ceiling, to a dimly lit attic lined with mahogany shelves, tall bookcases and curious artefacts its a cocoon-like space, a private library, perhaps.

Seated around a heavy central table are three nice little people dressed in dark brown hooded robes. The miniature monks tell Frisell they are going to show him stuff, the real stuff, how things really are. They are going to share special truths, secret quiddities that very few come to know. One of them takes from a shelf a small wooden box containing cubes of different colours. He invites Frisell to open it. This is the true essence of colour, what colour really looks like, he tells him.

Frisell looks at a red so bright and intense that it hurts his eyes: It was a red like Id never seen, like it was psychedelic or something, or lit from within. He has the same experience with blue and green: It was like Id been blind and was seeing colour for the first time.

Another monk then turns to Frisell and says, We know youre a musician, so wed like you to hear what real music sounds like.

The sound that streams into the room is so pure and physical that it feels like a rod passing through his head. It was like an arrow shot between my eyes or a rocket ship travelling through my brain, he explains. Its every piece of music he has imagined or heard, coexisting and playing simultaneously. Yet what could be cacophony coalesces into the most harmonious, beautiful and perfect music. Then suddenly, of course, Bill Frisell wakes up.

It was the most amazing thing Ive ever heard, though it would be impossible to describe, he tells me. He cannot recall what the melody was, be sure there even was one, or what type of music was being played: It was like one of those super-elaborate Chinese carved ivory [puzzle] balls you dont know how they do it, but the further and further you look inside, the more and more layers you discover. I sort of remember the sound of strings like a thousand violins playing independent parts. But it wasnt really a particular instrument, or instruments. And it wasnt a drone, because you could hear every little bit. It just included everything. It was all one thing. It was one sound.

His memory of the dream may be elusive, yet its meaning and significance to Bill Frisell seem more clear. On one level, the dream represents the ideal (and myth) of artistic perfection, the apogee of creative struggle and endeavour, the liminal, mysterious forces at work in music and the arts. On another, it symbolises Bill Frisells search.

I could never, in any way, achieve anything remotely close to what I heard in the dream, he says. But I got a glimpse of something to strive for, something real and concrete, something that I feel I actually heard. Something I know is there. Im always reaching out for things that are just a little bit beyond my grasp, different things that sort of float by a little outside my focus. Sometimes I reach out, and they disappear. But thats what keeps me going, every day, every time I play.

Frisell says he has experienced the sound, fleetingly, when playing in concert. There have been a few moments, just for a split second, when things have really lifted off, when Ive just totally lost whos playing what, and Ive had a tiny flash or reflection of that sound. Ive barely seen it; its like Im on a high-speed train. But its pretty awesome to even think that it might be there, to be reminded that maybe theres a way to get to all this stuff. Maybe thats what the beam or rod [of sound] means. Its about paying more attention, right? About staying clear, and making sure you somehow stay on target. Its about there being no reason why music cant be all together in one place.

It may seem fanciful, romantic even, to allude to the power of such a dreamworld in the music of Bill Frisell. Yet he is not the first musician to have experienced such a striking epiphany. The inimitable jazz original Rahsaan Roland Kirk said that the extraordinary innovation of playing more than one horn at the same time came directly from a dream. The idea came from a whole lot of different dreams that I was having, he once said. Id be so frustrated after Id practised, day in and day out. And Id lay down and have these dreams; Id hear different instruments simultaneously one of the dreams showed me playing two instruments simultaneously. So after that I set out to find the instruments that I heard in my dreams, by looking in antique shops and different types of music shops and things.

From Paul McCartney to Keith Richards, Johnny Cash to Jimi Hendrix, Wagner to Ravel, Stravinsky and Berlioz, countless musicians and composers have said songs and compositions have come partially or fully formed to them in dreams. Jazz pianist Dave Brubeck even claimed to have found religion through a reverie of music. After hearing in a dream an entire composition and orchestration of the prayer Our Father for a mass he had been commissioned to write, he was reportedly so moved by the revelation that he joined the Catholic Church.

The influence of Frisells dream continues to resonate. He has written compositions with oneiric titles such as Like Dreamers Do, Dream On and Shutter, Dream. Then there are the albums Beautiful Dreamers, which includes a gently oblique version of Stephen Fosters 1864 parlour song Beautiful Dreamer, and Blues Dream, a suite of songs that stretches and expands across many American musical forms, and is widely considered to be one of his finest works. Beautiful Dreamers also became the name of one of Frisells most consistently creative groups, a trio with Eyvind Kang on viola and Rudy Royston on drums.

Those whove worked closely with Frisell recognise the dream, and the search, as being important and revealing.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, that sounds exactly what Bill is like, says drummer Kenny Wollesen, when I describe The Frisell Dream to him. Because he has these ears that just capture everything. I mean, its amazing, man; crazy. Its all going into his brain, and it makes me realise that theres a lot more going on than what Im hearing.