Table of Contents

List of tables

- Tables in Chapter 6

List of illustrations

- Figures in Chapter 1

- Figures in Chapter 2

- Figures in Chapter 3

- Figures in Chapter 4

- Figures in Chapter 5

- Figures in Chapter 6

- Figures in Chapter 7

- Figures in Chapter 8

- Figures in Chapter 9

- Figures in Appendix C

Landmarks

Table of Contents

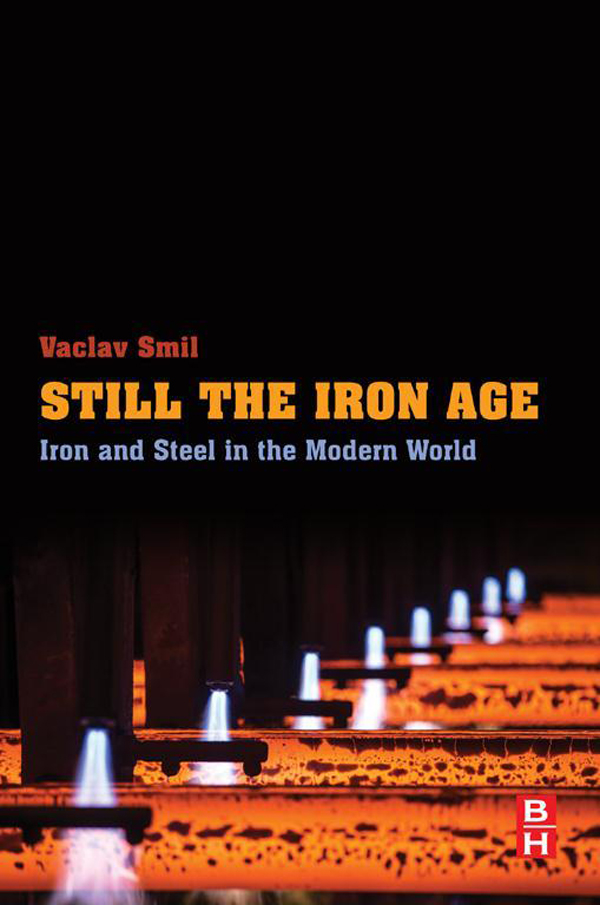

Still the Iron Age

Iron and Steel in the Modern World

Vaclav Smil

Copyright

Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

Copyright 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publishers permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN: 978-0-12-804233-5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

For Information on all Butterworth-Heinemann publications visit our website at http://store.elsevier.com/

Preface and Acknowledgments

My books are expressions of my preference for writing about fundamental realities, be they natural or anthropogenic, and their complex interactions. That is why I have written extensively on the Earths biosphere and its transformations by humans, on production of foods and changing diets, on energy resources and on material foundations of our civilization. Besides dealing with these matters in systematic, universal and generalized manner (the best example would be General Energetics, Global Ecology, Feeding the World, Energy in Nature and Society, Harvesting the Biosphere and Making the Modern World) I have taken some closer looks, writing books focusing on specific fundamentals of modern civilization: on wood and other biofuels (Biomass Energies), oil (Oil: A Beginners Guide), natural gas (Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century), ammonia (Enriching the Earth), Diesel engines and gas turbines (Prime Movers of Globalization), and meat (Should We Eat Meat?). This book is simply a continuation of my efforts to deal with such fundamental realities and it has been on my list of to do items since the early 1990s when I began to study the long history and remarkable accomplishments of iron smelting and steel making.

Those who appreciate the physical foundations of modern societies do not need any convincing about the topics importance. Those who think that mobile phones and Facebook and Twitter accounts are the fundamentals as well as the pinnacles of modern civilization might find the book about iron and steel inexplicably antiquated: their realities appear to be purely silicon-based. But that, of course, demonstrates deep lack of understanding of how the world works. Modern civilization could exist quite well without mobile phones and social media; indeed, in the first instance it did so until the 1990s (beginning of large-scale adoption of cellphones) and in the second instance until the late 2000s (when the Facebook membership took off). In contrast, none of its great accomplishmentsits surfeit of energy, its abundance of food, its high quality of life, its unprecedented longevity and mobility and, indeed, its electronic infatuationswould be possible without massive smelting of iron and production (and increasingly also recycling) of steel.

In the 1830s Danish archeologist Christian Jrgensen Thomsen (17881865) distinguished three great civilization eras based on their dominant hard materials, with the Bronze Age following the Stone Age and preceding the Iron Age (). Transition from stone to bronze began about 3300 BCE in the Near East and just a bit later in Europe, the onset of Iron Age was around 1200 BCE but it took another 7001000 years before the metal became dominant throughout Asia and Europe. When Thomsen made his division, the Iron Age was mostly 20002500 years old, but the time of the greatest dependence on the metal was still to come, and at the beginning of the twenty-first century no other material has emerged to end that dominance. Ours isstill and more than everthe Iron Age although most of the metal is now deployed as many varieties of steel, alloys of iron and carbon (typically less than 2% C) and often of other metals that impart many desirable qualities absent in pure elemental iron.

The great nineteenth-century surge in iron smelting and steel production continued during the twentieth century as the long-lasting US technical leadership shifted to Japan after 1960. Four decades later the rapid expansion of Chinas economy brought the iron and steel output to unprecedented levels during the first decade of the twenty-first century. By 2015 iron ore extraction was more than 2 billion tonnes (Gt), the mass surpassed only by the annual output of fossil fuels and bulk construction materials; pig (cast) iron production (smelting of iron ores in blast furnaces) rose to more than 1 Gt; and the global steel output (from pig iron or from recycled metal) reached about 1.7 Gt. That output was about 60 times higher than in 1900, and roughly 20 times larger than the aggregate smelting of aluminum, copper, zinc, lead and tin. And in per capita terms worldwide steel output rose by an order of magnitude, from 20 kg/year in 1900 to about 230 kg/year by 2010.

Perhaps the best way to stress the importance of steel in modern society is to note that so many components, parts, machines and assemblies are made of steel and that just about everything around us is made or moved with it. Although naked steel is not uncommonranging from such small items as needles, pins, nails, construction, laboratory and medical tools to slender broadcasting towers, wires, cables, rails and bridge spans and girdersmost of the metal incorporated in modern products is hidden (inside structures as reinforcing bars in concrete, skeletons of large buildings, inside machines as engines and turbines or underground in piles, pipelines, tunnels and mine props) or covered by layers of paint (welded ship hulls, construction machinery, cars, appliances, storage tanks).