For American men and women who work in iron and steel.

Iron seemeth a simple metal, but in its nature are many mysteries and men who bend to them their minds shall, in arriving days, gather therefrom great profits not to themselves alone but to all mankind.

Joseph Granvill, 1668

STEEL

FROM MINE TO MILL, THE METAL THAT MADE AMERICA

BROOKE C. STODDARD

First published in 2015 by Zenith Press, an imprint of Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc., 400 First Avenue North, Suite 400, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

2015 Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc.

Text 2015 Brooke C. Stoddard

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purposes of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or Publisher, who also disclaims any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

We recognize, further, that some words, model names, and designations mentioned herein are the property of the trademark holder. We use them for identification purposes only. This is not an official publication.

Zenith Press titles are also available at discounts in bulk quantity for industrial or sales-promotional use. For details write to Special Sales Manager at Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc., 400 First Avenue North, Suite 400, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA.

To find out more about our books, visit us online at www.zenithpress.com.

Digital edition: 978-1-62788-665-9

Hardcover edition: 978-0-76034-742-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stoddard, Brooke C., 1947- author.

Steel : from mine to mill, the metal that made America / Brooke C. Stoddard.

pages cm

Summary: A history of steel, an examination of its impact on civilization, and a firsthand look at how it is made today-- Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-7603-4742-3 (hardback)

1. Steel--History. 2. Steel industry and trade--United States. I. Title.

TN703.S76 2015

669.10973--dc23

2014049417

Acquisitions Editor: Elizabeth Demers

Project Manager: Madeleine Vasaly

Art Director: Cindy Samargia Laun

Cover Designer: Kent Jensen

Book Designer: John Barnett and Karl Laun

On the cover: sdlgzps/Getty Images

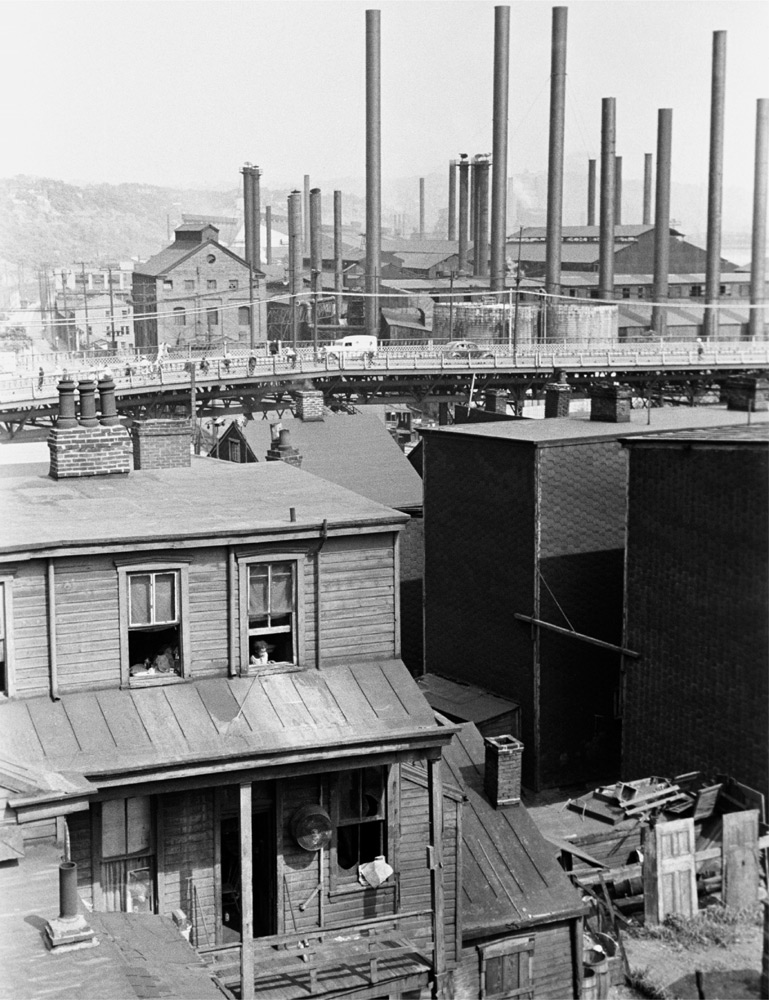

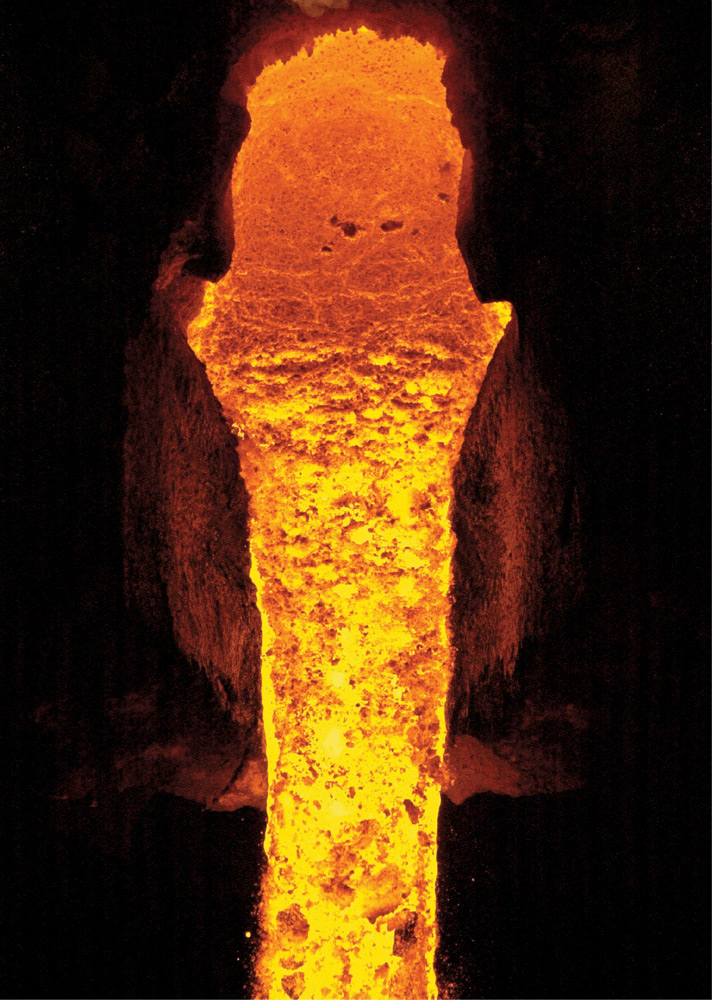

On the following pages: Slum housing near steel mills of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1938 (Everett Historical); molten steel (Wade H. Massie/Shutterstock)

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

S teel is an alloy of iron, which is not an uncommon metal. But humanity found making steel difficult, especially in quantity, and no one was able to do so until Englishman Henry Bessemer invented machinery that could produce steel by the ton. The result radically altered civilizationsteel made the industrialized world. It made railroads, bridges, skyscrapers, cargo ships, battleships, manufacturing machines, electricity grids, food containers, cars, and trucks. Steel also made America a world power.

In the mid-1980s, the American steel industry was making headlines it loathed. Because of global competition and domestic blunders, steel mills were closing. Communities and politicians wailed and called for protective government policies. People wondered how the steel industry might reform itself.

I wondered about something else: how steel was actually made. So I researched the industrys history and technology. The history was in books, but for the rest I descended into open pit iron mines, rode an iron-ore boat from Lake Superior to Cleveland, and spent time among blast furnaces, steel furnace mills, and rolling mills. Given the nations interest in the steel industry I expected my inquiry to find a backer. I was wrong, and none came forth until now. I am grateful to Zenith Press in joining with me for explaining both how steel is made and something of its impact on the world.

The steel industry in the United States has changed since I spent time in the mills. It employs fewer persons. It composes less of the national economy. Open-hearth steel furnaces have largely given way to what are called basic oxygen furnaces (BOFs), which produce steel faster. Ingot rolling has largely given way to what are called continuous casters.

But much is the same; in fact, it can hardly be altered. Iron ore has to be mined in immense quantities and then smelted, mainly in gigantic blast furnaces that spew liquid iron out the bottom at 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit (lava from volcanoes being 1,300 to 2,200 degrees). The resulting pig iron, running almost as thin as water and too bright to look at directly, then has to be refined in steelmaking furnaces. Finally, the steel has to be shaped by rolling mills into I-beams, sheet metal, or other products. Never think of steelmaking as somehow low tech; it requires an immense sophistication of chemistry and physics, and it is spectacular.

The text that follows is mainly about integrated steel millsones that convert iron ore into steel, the kind of mills that built up America and continue to convert undeveloped countries into developed ones. Non-integrated mills feed on scrap steel rather than ore, and although these produce an increasing share of the nations steel, it is the integrated mills that are to the economy as rain is to the farmer: basic and necessary. Integrated mills are fewer now in America than during their heyday of the decades of two world wars. But they are the mother lode of steel, and steel continues to be the backbone of industrialized societies.

INTRODUCTION

I n 1881, the United States surpassed the United Kingdom as the largest producer of steel in the world. Nine years later, the United States was producing five million tons of steel a yearalmost equal to the outputs of Germany and Britain combinedand nine years after that, in 1900, it had doubled its annual output to 11 million tons. By midcentury, near Baltimore on a rectangle of land along Chesapeake Bay larger than the downtown of the city itself, as many as thirty thousand workers toiled day and night in a six-square-mile warren of blast furnaces, steelmaking hearths, and rolling mills. Similar mills produced steel in or near Cleveland, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Buffalo, Birmingham, and even Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, as well as smaller cities such as Youngstown, Weirton, Aliquippa, and Johnstown. The mills heated cold iron ore until it ran like water at almost three thousand degrees and then with precise chemistry turned the molten iron into steel. The mills made I-beams, rails, ship hulls, bridge trusses, food cans, and rolls of sheet steel for automobiles and trucks.

Steel made the modern United States. In fact, steel made all industrialized nations. A country was measured by the amount of steel it produced. Iron and steel assured Great Britain of world leadership in the nineteenth century, as they did somewhat later for Germany and France. The United States rose to world power on the volume of the steel it made. In the twentieth century the Soviet Union pursued steelmaking with a passion, coupled to the belief that its mills would make the communist country a global power. Japan was of like mind and set itself to be the premier steel producer and lord in East Asia. China, India, Brazil, and South Korea, all emerging industrialized nations, have fueled their development with steel mills.

Next page