Copyright 2014 Dale Richard Perelman

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 149734140X

ISBN 13: 9781497341401

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014905150

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

North Charleston, South Carolina

CONTENTS

I

PREFACE

T he book, Steel, juxtaposes Pittsburghs wealthy iron and steel manufacturers of the 19th century against the immigrant labor force who toiled in their mills and mines. Titans Andrew Carnegie, Henry Oliver, and Henry Phipps lived in poverty as children. Most of these industrialists were first or second-generation Western Europeans - Scottish, English, Welsh, Scottish-Irish, or German Presbyterians and imbued with a strong spirit of capitalism and the belief in their own God-given superiority. In contrast, the laborers in the mills and mines generally were Eastern European - Russian, Polish, Hungarian, and Slavic Catholic or Orthodox peasants. The bosses displayed minimal concern for the safety and welfare of the unskilled workforce, who suffered the ravages of disease, inadequate sanitation, poor nutrition, and a dangerous workplace.

Although abundant information is available on the plant owners like Andrew Carnegie, B. F. Jones, Henry Oliver, Henry Phipps, Charlie Schwab, and Henry Clay Frick, relatively little information exists on the worker population, many who spoke little or no English. I have relied heavily on the descriptions told to me by their descendants and thus have taken a degree of poetic license with the details of their story although the basic truths are factual.

I wish to thank my wife Michele for her unwavering support, excellent editorial assistance, and photography as well as my two children, Sean and Robyn, who each are very proficient writers. My appreciation extends to the Yale Writers Conference and to my two instructors: M. G. Lord and Hope Dillon. I especially enjoyed attending Yale with my good friend and guru-novelist Phil Gasiewicz. I also wish to acknowledge artist Ron Donoughe for allowing me to use his oil painting Vertical Pour for my cover. Graphologist Dr. Peter Mancino delivered spot-on personality analysis of the major characters. Reader Cynthia McNickle gave me the encouragement I needed. Editor Heather Lundine helped shape the story, and curator Heather Semple twice led me and my wife on a Duquesne Club tour and permitted the reproduction of Aaron Harry Gorsons 1903 painting, Mills in Winter, and Frank DeAndreas 1885 painting, The Blast Furnaces of Pittsburgh.

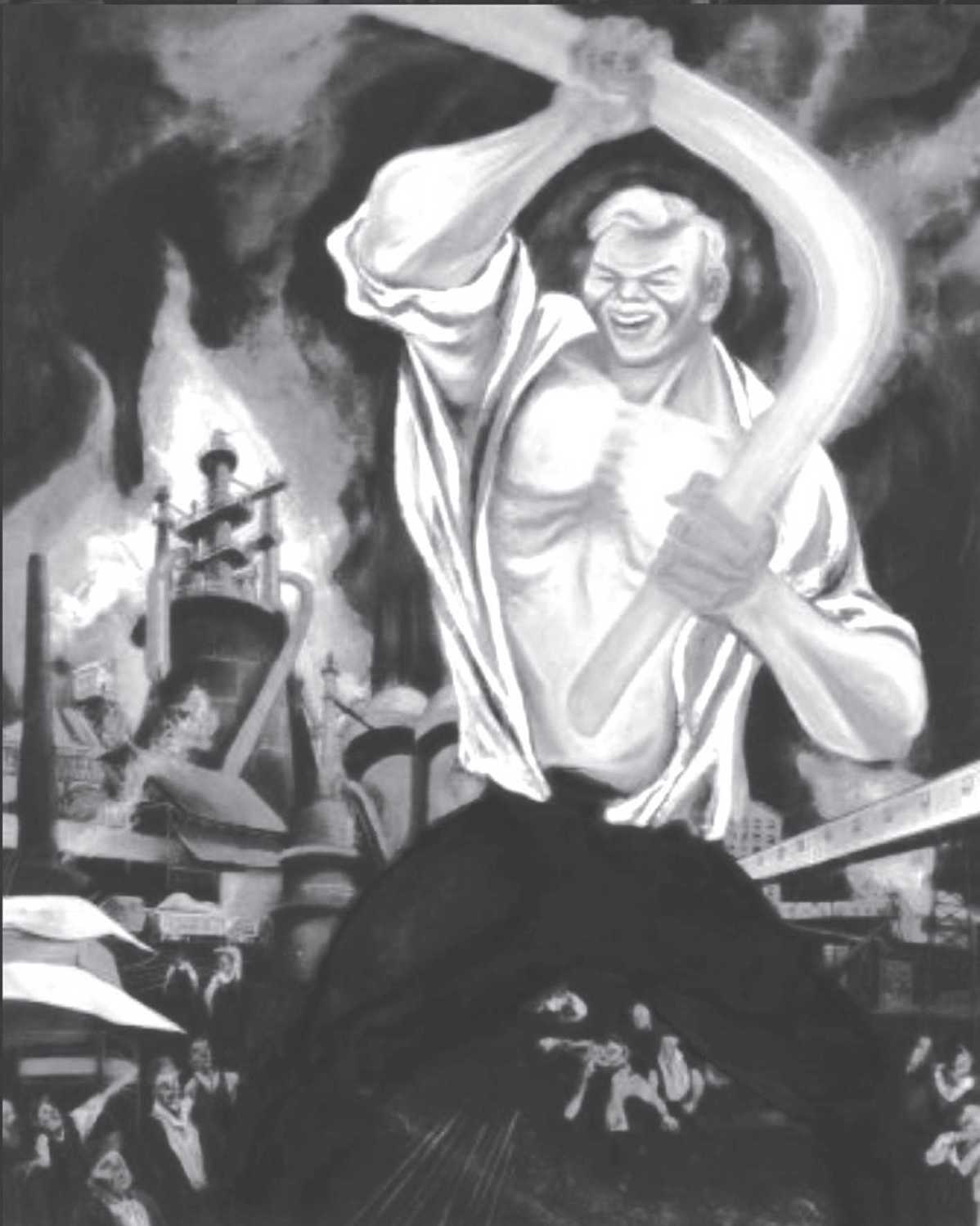

JOE MAGARAC COULD BEND STEEL RAILS WITH HIS BARE HANDS

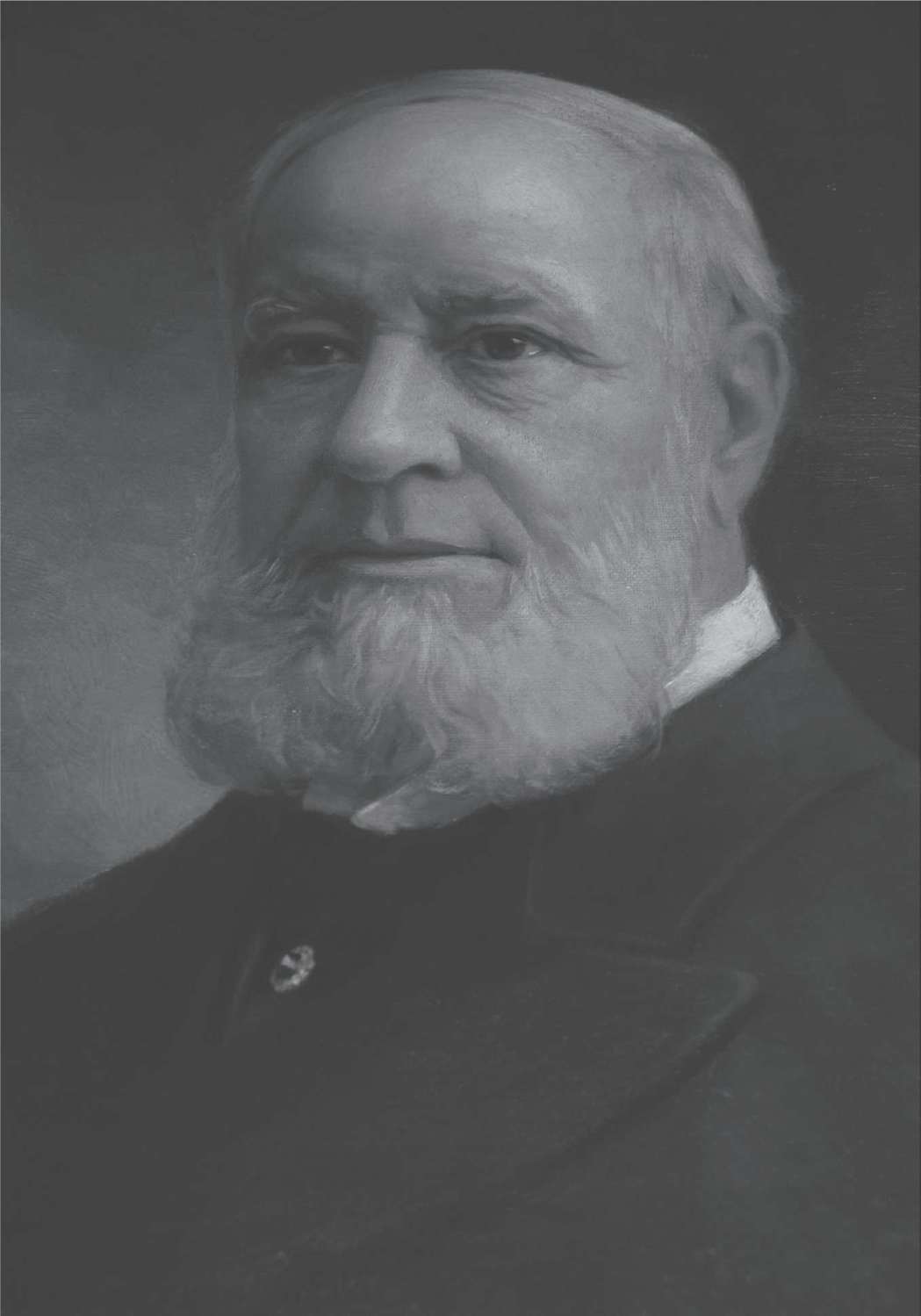

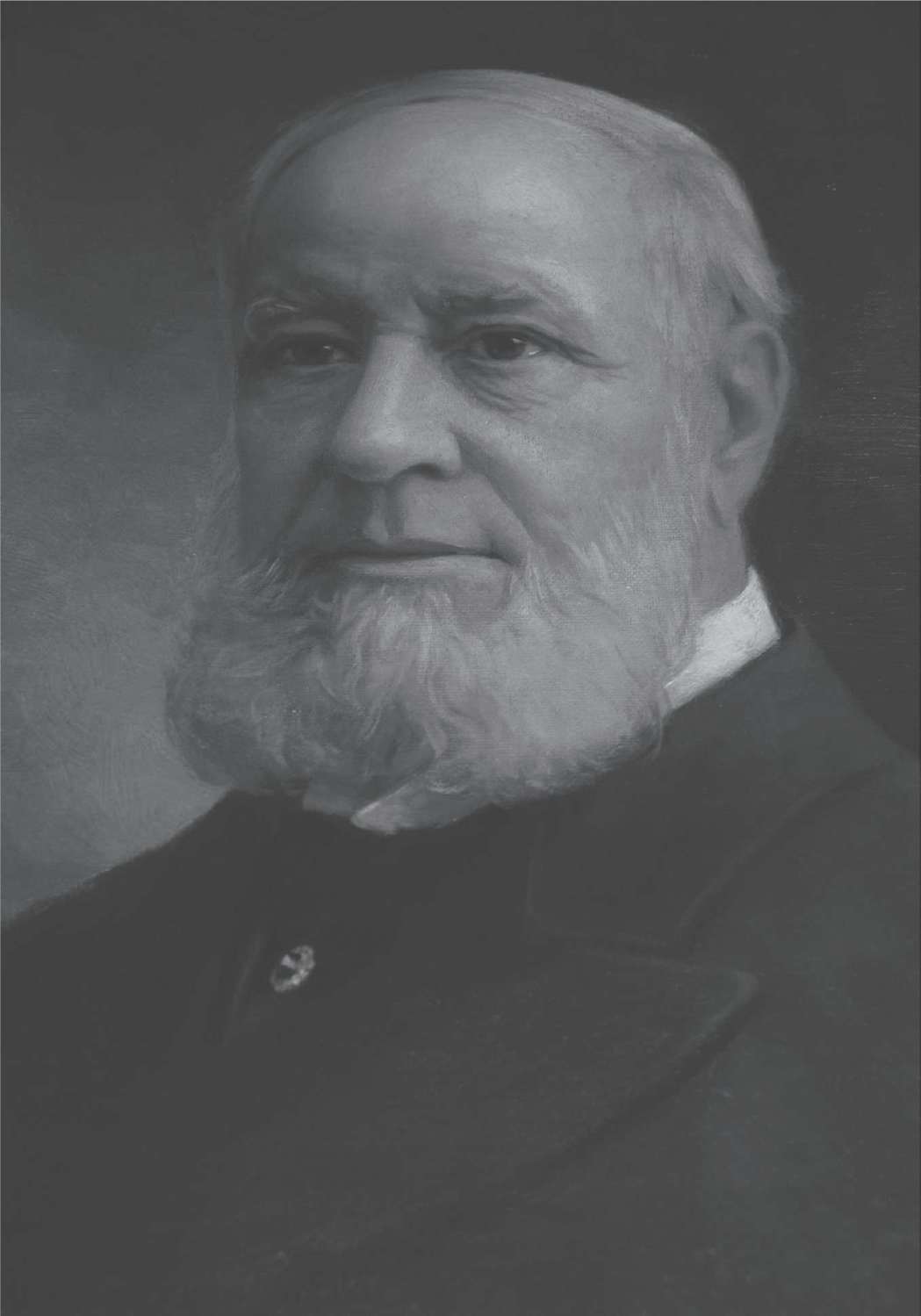

BEN FRANKLIN JONES

CHAPTER 1

IRON

T he J. Edgar Thomson steel plant was the finest in Pittsburgh, probably in the world, and its superintendent Captain William Richard Jones was the countrys most celebrated steel man. He ran an efficient plant, the pride of the Carnegie Empire. The short, tough, fifty-year-old superintendent had worked his way through the ranks, starting as a machinists mate at age ten. He had enlisted as a private in the Union army during the Civil War and earned a battlefield commission to captain. Now, he managed the steel industrys largest mill.

On Thursday evening, September 26, 1889, six of the plants seven furnaces were humming. Day and night, J. Edgar Thomson pounded out record output under Joness firm hand. The second shift had gone smoothly except that damned Furnace C. It had been acting up all day.

Capn, come quick! Mr. Gayley needs you, yelped a sweaty laborer.

Jones did not tolerate production snags, whether caused by man or machine. Getting into the action was part of the job. Let me take a look, he grunted. A clump of slag and coke had blocked the furnace like a flotsam and jetsam of logs damming the flow of a river. The team had to react quickly to avoid an explosion from the building pressure.

Sparks flew and the furnace roared as the men tapped the line with a sledge hammer to reduce pressure. Keep at it, exhorted an impatient Jones.

Shit, it aint tapping, shouted a Hungarian laborer, pounding furiously at the metal rod held in place by worker Michael King. Were in trouble. Pressures a buildin fast! The struggling workers stepped aside to let Jones take a look.

Jones entered the fray with the same intensity he had demonstrated as an officer with the 87th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg. He grabbed the hammer from the Hungarian laborer and swung with all his strength to attack the blockage.

Without warning, a one-foot metal sheet just above Jones head flew from the furnace spraying a deadly wave of cinder ash and molten steel. The onrush encased the unfortunate Hungarian laborer in a steel in got. His body would not be discovered until the following day. Michael King dissolved, boiled in a lava-flow of steam, buried in a shipment of rails. The wall of liquid death showered Jones in a bath of molten steel, scalding his face and hands.

Jones leapt for safety, but he struck his skull on a nearby railcar. The team reacted swiftly. A foreman shut down the blast to the furnace halting the hail of flames and fire - too late. A nearby worker dragged the semi-comatose Jones to the safety of an empty room where a physician treated his burns and summoned a gurney. Jones moaned incoherently. He never regained consciousness and died in the Homeopathic Hospital three days later.

Thousands attended the superintendents funeral on October 2nd. The Capn, as the men called him, had been no ordinary manager. He got his hands dirty and knew steel. He would chip in when the going got tough, and thats what killed him. He could be a bastard, tough, ornery, and mean, but at least he was our bastard, spouted one worker, summarizing the general feelings of the plant. Kelly, one of the two others killed in the accident, had been a good Mick, but now a dead one, eulogized another worker. There but for the grace of God lay I, on my back in a pine coffin, thought a third laborer as he cocooned in the safety of his row house after the funeral.

Carnegie Steel executives Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Carnegie served as honorary pallbearers although Jones had liked neither man. Workers from the plant escorted the coffin to what is now called Homewood Cemetery.

Only family and close friends would mourn the laborers, Michael King and the nameless Hungarian. Carnegie could easily replace an unskilled worker with another hungry body, but Joness death proved downright inconvenient for the team at Carnegie Steel. He had been an asset who drove plant production to record levels and developed dozens of valuable patents including a Feeding Apparatus for Rolling Mills, an Apparatus for Removing and Setting Rolls, and a Hot Bed for Bending Rails. The Mixer Jones invented combined several steps in the manufacturing process, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars while providing J. Edgar Thomson with a distinct competitive advantage over its rivals.

The day after the funeral, the pony-sized bundle of nerves Henry Phipps, a Carnegie partner and a financial officer, accompanied by Henry Curry, the plants furnace supervisor, knocked on widow Harriet Joness door hat in hand. The executives ostensibly came to offer their condolences, but they had an ulterior mission. Phipps carefully explained how all patents filed on company time belonged to Carnegie Steel. He glanced toward a picture of Captain William Jones in his Civil War uniform on the mantel before shifting his gaze. A tear formed on the widows cheek, and Phipps felt a twinge of sympathy. Harriet Jones already had lost two of her four children at an early age and now a husband. Phipps continued. As a reward for your husbands years of service and his-unfortunate untimely death, the company graciously is offering a lump-sum settlement of $35,000, provided you sign over all Captain Joness patents. Harriet Jones knew $35,000 represented a fortune, and possibly a fair price, even though her husband earned the unheard of salary of $25,000 per year. The amount offered would feed and clothe her family for as long as she lived. The grieving widow signed the document without objection, anxious to have these men go and grateful for the money.

Next page