Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Ryan C. Brown

All rights reserved

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.791.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943512

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.258.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Kelly

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Nothing of value is built solely by its immediate creator. The great libraries and museums that bear the names of steel moguls could only be built through the work of the mills, just as the millworkers relied on ore and coal miners, railroad workers and thousands of unsung wives and mothers.

Similarly, this book isnt the sole work of its author; many family members, friends, teachers and advisors helped along the way, and each lent their own labor and value to the final product.

This book couldnt be in your hands without the editors and artists at The History Press who aided me at every step.

I would like to thank my wife, Kelly, whose encouragement and patience made this project possible. I would also like to thank my mother, Laura; my father, Chris; my stepfather, Dustin; my stepmother, Brenda; and my wifes parents, Greg and Cheryl, who all contributed time and energy to make our lives easier while I researched and wrote this book. I want to thank my brother, Simon, who offered advice as a historian, and my grandparents Herbert and Shirley Brankleyboth are Pittsburgh natives who raised a family there and provided inspiration for this book.

I owe thanks to my former newspaper coworkers and editors, whose advice helped sharpen my writing, and to Lee Wood, whose tough journalism lessons hopefully helped keep this book clear and concise. I would also like to thank Jared Frederick of Penn State Altoona, a friend and talented historian who encouraged me to begin this project.

This book would not have been possible without the aid of researchers, particularly those who maintain archives and online repositories to little fanfare. I extend my thanks to the archivists at the University of Pittsburgh, the Historic Pittsburgh collections and to Tim Davenport, whose online collection of American Marxist history was of great help.

While I relied on the work of many great authors, researchers and journalists, a special thanks is owed to Charles H. McCormick, whose book Seeing Reds was of singular importance.

I thank those around Pittsburgh who have worked to preserve the citys industrial and labor heritage. Groups like the Battle of Homestead Foundation have been an invaluable resource.

Lastly, I thank the many union members, labor activists and organizers whom I have had the honor to meet and work with. Their perspectives on todays conflicts helped me understand the labor battles of a century past.

INTRODUCTION

From the steps of the Good Shepherd Catholic Parish in Braddock, Pennsylvania, there are two buildings that catch the eye. First, just a few yards away across Braddock Avenue, is the office of the United Steelworkers Local 1219. Behind it, looming over the city like a rusty blue ship, is the Edgar Thomson Plant of the United States Steel Corporation.

The plant stretches along the Monongahela River and is crisscrossed by railroad tracks and power lines. It can churn out millions of tons of steel each year that is shipped to other U.S. Steel facilities that still dot the Pennsylvania valleys. It has stood there, in one form or another, since the 1870s, when the plants Bessemer converter first poured out its purified steel. The monstrous ladles and chargers have been modernized, but still, the plant makes steel.

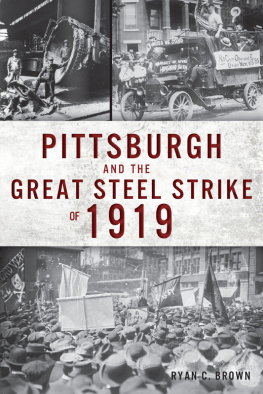

Its easy to miss the office of Local 1219 in the mills shadow. The low-slung building is host to occasional union meetings and Steelers viewing parties, and a few cars can usually be found parked along Eleventh Street. A visitor might find it hard to imagine the scene that was on that street in October 1919: crowds of men openly battling outside the mill, replacement workers fighting their way inside under police guard, a state constable wounded in the mle, a man shotits not clear who, which was often the case in the chaotic and garbled reports that flowed from the battles in every steel town. The Pittsburgh Gazette Times could only report that Washington Street was the scene of other troubles between strike sympathizers and workmen during the day.

There was no union hall then. The workers, who spent twelve-hour days and seven-day weeks in the blazing mill, had no union, at least not a recognized one. Those who joined risked dismissal, the blacklist and beatings by industrial agents. An unprecedented organizing drive had spurred thousands of workers around Pittsburgh to join the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, which sought a raft of reforms and recognition to bargain as equals with the millionaire steel bosses. However, it was nothing like todays organizing drives. From the 1930s until the modern wave of so-called right-to-work legislation, workers and employers in the United States dealt on the principle that a fairly elected union represented all the employees under its jurisdiction. But in 1919, the steel bosses were under no obligation to make a deal. They fought the organizers, and their supporters, with government support.

For months, the valleys around Pittsburghthe Monongahela, the Allegheny, the Ohio, the Shenango, the Conemaugh and many morewere in an effective state of war. Sheriffs deputized thousands of civilians and handed enforcement of the law over to eager, anti-union men and soldiers fresh from the trenches of World War I in France. Strikers armed themselves and surrounded the mills, desperate to keep replacements from relighting the furnaces. Many diedtwenty according to organizersbut figures vary. At the time, it was the largest strike in America.

There was a church in Braddocks battlefield, too, but the Good Shepherd Parish had not yet been built. Its predecessor, St. Michaels Parish, rang with the songs of Slovak immigrants who had crossed an ocean to work in the mills. The workers had crossed from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and their families often followed. Along with them were thousands of poor immigrants from the new and old nations of Europe: Russia, Poland, Romania and Croatia. Those immigrants were at the heart of the strike, and at St. Michaels, the parish priest tended to their hungry families and stood with their union. When the authorities threatened the church, the priest vowed to fly a banner atop the steeple to place blame on the steel bosses.

The immigrants also brought with them new ideas from Europe, which terrified steel moguls, newspapermen and politicians alike. Across Pittsburgh and its surrounding towns, socialist meeting halls and schools sprung up. Parties and unions with strange names formed, and their meetings were sometimes carried out in strange languages. Lenin and Trotsky became household names in America. Among Pittsburghs immigrantsand its natural-born citizensgroups like the Communist Labor Party, the Union of Russian Workers and the Industrial Workers of the World drew newfound attention. Why work for wages? they asked. They said that system that allowed steel moguls to live in sprawling mountain castles while condemning steelworkers to shantytowns couldnt last. A general strike, a workers uprising, could end it.