Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by John F. Hogan

All rights reserved

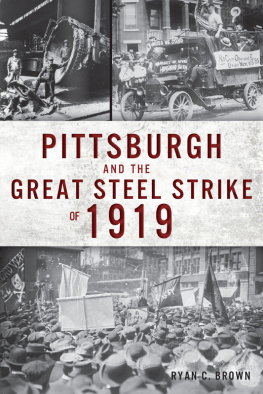

Front cover: Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.835.2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hogan, John F.

The 1937 Chicago steel strike : blood on the prairie / John F. Hogan.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-343-7

1. Little Steel Strike, U.S., 1937. 2. Strikes and lockouts--Steel industry--Illinois--Chicago--History--20th century. 3. Industrial relations--Illinois--Chicago--History--20th century. 4. Demonstrations--Illinois--Chicago. 5. Police brutality--Illinois--Chicago. I. Title.

HD5384.I521937 H64 2013

331.892869142097731109044--dc23

2013048439

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

Although I come from a police family and worked a summer break from college on the open-hearth furnaces at Republic Steels South Chicago plant, I dont remember anyone in either setting mentioning the tragic 1937 Memorial Day encounter. I became only vaguely aware of the fatal episode sometime later, probably from reading cryptic flashbacks in the newspapers. Even today, when I mention the event to informed longtime Chicagoans, I often find that Im telling them something theyre hearing for the first time. Chicago Fire Department historian John Rice has suggested that tragic events such as the Iroquois Theater fire or the capsizing of the SS Eastland become part of a collective amnesia because people dont want to remember something so horrible.

The Memorial Day incidentor massacre, as many call itwas horrible; it never should have happened. The eight minutes of newsreel footage recorded that day depict a police riot, to borrow a term from the presidential commission that investigated the disturbances at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. What happened on May 30, 1937, far exceeded anything that transpired thirty-one years later. The police shot forty people, ten fatally. All but four were hit from the back or side. Dozens were clubbed as they fled a tear gas barrage, some as they lay defenseless.

Steelworkers Local 1033 has conducted periodic memorial gatherings to keep the memory fresh. A sculpture dedicated to those killed stands a half block north of the union hall on the citys Southeast Side, the building itself dedicated to the dead of 1937. Like the Iroquois, the Eastland or the Stock Yards Fire of 1910, this is a chapter of Chicago history that deserves to be preserved. This account is not intended to be pro or anti union, industry, police or governmentlocal, state or federal. What follows, I hope, is a straightforward presentation of the facts in an attempt to capture a seminal period of labor history and, more specifically, the tragic event that marked its nadir. The heroes, rogues and those between, on all sides, identify themselves through their own words and actions.

Like most everything Ive attempted to write, this project would not have reached final form without the invaluable help of my editor-in-chiefand spouseJudy Ellen Brady, who took time away from writing her own book to keep me on course.

Friend, neighbor and professional editor Andrea Swank, who is always there when my work requires doctoring, acquitted herself with distinction once again.

Alex Burkholder, my collaborator on Fire Strikes the Chicago Stock Yards, shared his extensive knowledge of Chicago history while also providing encouragement and a big assist with the graphics.

The last president of Local 1033, United Steelworkers of America (USWA), Victor Storino, was most generous with his time and access to the unions files. Victor and his brothers and sisters in the Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees (SOAR), as feisty and likable a bunch of seniors as anyone would care to meet, made me feel welcome from the outset.

The research staffs at three of my offices, the Chicago History Museum (CHM), Newberry Library and the Municipal Reference division of the Chicago Public Library (CPL), were unfailingly helpful and friendly, as always, even when confronted with dumb questions. A fourth office, the John Merlo Branch of the CPL, offered a quiet retreat for writing, particularly on winter days with snow covering the front lawn of the church rectory next door, seen through the Merlos west windows.

Elizabeth Murray Clemens of the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University in Detroit and Emily K. Harris of the United Mine Workers Union (UMW) in Washington, D.C., graciously responded to requests for photographic material. The Illinois Labor History Society in Chicago also provided help with visuals.

When I called Adriana Schroeder, the historian of the Illinois National Guard in Springfield, she found herself inundated with requests for information regarding the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Nonetheless, she allotted all the time I needed for background on the National Guards part in the Republic strike. Doing so, she handed this old reporter a small scoopthe long-confidential identity of the undercover National Guard officer who provided the governor with intelligence before, during and after the Memorial Day encounter.

Family friend and research librarian Carla Owens answered an urgent eleventh-hour call to help finish the project. Judy and I still owe you and Matthew that dinner, Carla.

CHAPTER 1

GODFATHERS

The rural Midwest in the last quarter of the nineteenth century hardly could have produced two more philosophically dissimilar national figures. Born three years apart, Tom (Tom, not Thomas) Mercer Girdler and John Lewellen Lewis now seem as though they were preordained to follow a collision course as the interaction of labor and capital became revolutionized, often with tragic results. Girdler and Lewis personified the immovable object and the irresistible force. They bestrode the American stage, alternately cajoling and defying federal and state bureaucrats, Congress and even presidents in pursuit of their diametrically opposed visions.

By the late 1930s, the pipe-smoking Girdler, chairman of Republic Steel Corporation and president of the American Iron and Steel Institute, and United Mine Workers chief and CIO founder Lewis, who favored cigars, together commanded hundreds of thousands of blue-collar workers with a stake on both sides of the divide. Lewis, with his massive head, leonine mane, perpetually glowering visage and, above all, eyebrows sufficiently overgrown to accommodate three faces, was by far the most visible and well known. (The Chicago Tribune, no fan of organized labor or its leaders, delighted in describing Lewis as beetle-browed. He was a cartoonists godsend.) In the 30s and 40s, his image loomed almost as prominently in newspapers and movie newsreels as that of President Roosevelt, whose jutting chin and jaunty cigarette holder also were no strangers to caricature. Tom Girdler, on the other hand, would fail to stand out in any CEO group portrait, a very ordinary-looking man who wore round, dark-rimmed glasses perched below an expanse of full-frontal baldness. Yet the bland exterior masked an extraordinary individual, just as hard-nosed as Lewis, though unlike his adversary, Tough Tom, as he was called, was known to smile occasionally.