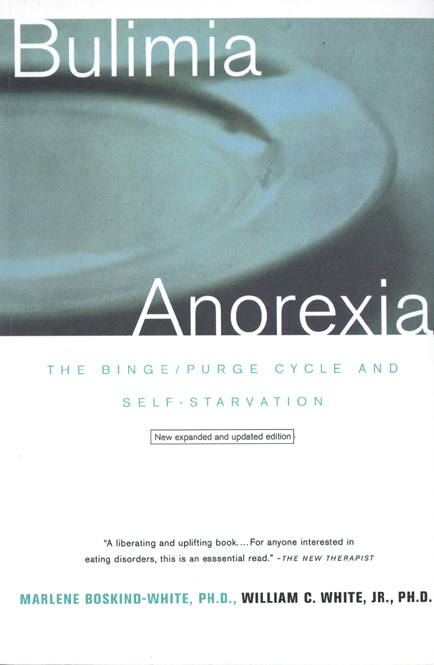

Bulimia / Anorexia

THE BINGE / PURGE CYCLE AND SELF-STARVATION

Marlene Boskind-White, Ph.D.

William C. White, Jr., Ph.D.

W W NORTON & COMPANY  New York London

New York London

Copyright 2000 by Marlene Boskind-White

Copyright 1987, 1983 by Marlene Boskind-White and William C. White, Jr.

First published as a Norton paperback 2001

Previous editions published as Bulimarexia: The Binge/Purge Cycle

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

The text and display of this book are composed in Adobe Garamond

Composition by Allentown Digital Services Division of RR Donnelly & Sons Company

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Boskind-White, Marlene.

Bulimia/anorexia : the binge/purge cycle and self-starvation / Marlene Boskind-White, William C. White, Jr.[3rd ed.].

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: Bulimarexia. 2nd ed. 1987.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-31923-1

ISBN 978-0-393-35489-8

1. Bulimia. 2. Anorexia nervosa. 3. WomenMental health. 4. Eating disorders. I. White, William C, Jr. II. Boskind-White, Marlene. Bulimarexia. III. Title.

RC552.B84 B67 2000

616.85263dc21

99-045784

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To my beloved husband

William C. White, Jr.

19401998

BULIMAREXIA, the binge/purge syndrome, was introduced to the professional and popular literature in a series of articles William C. White, Jr. and I published in the 1970s. At that time during our initial research at Cornell University, the diagnostic category bulimia was described as a rare disorder that involved binge eating with no reference to purging and, like anorexia nervosa, was overwhelmingly interpreted and managed within the boundaries of psychoanalytic theory. Many of the young women who responded to our initial outreach efforts had been previously labeled anorexic by therapists, and most found the clinical description of the emaciated anorexic foreign and frightening. This diagnosis seemed inappropriate for women whose weights were within normal ranges and who were not starving themselves. Rather, these women were bingeing on copious quantities of food and purging themselves via forced vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, constant dieting, and/or excessive exercise.

Bulimarexia distinguished the binge/purge cycle from bulimia and anorexia nervosa. We also chose the new word to better reflect our view that binge/purge practices represented tenacious habits, not disease processes. We believed bingeing and purging were learned behaviors that could be unlearned, utilizing the principles of social learning theory. Bulimarexia was thus defined in terms of specific primary and secondary behaviors. This definition became commensurate with the revised third edition of the American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and the terms bulimia nervosa and bulimarexia have come to be used interchangeably. In this new edition of Bulimarexia I have changed the books title to reflect the new accepted wider meaning of bulimia as well as the inclusion of new material on anorexia but to minimize resetting have retained the term bulimarexia in the original text. In the 1994 Fourth Edition of the DSM, the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were revised as follows:

307.1 Anorexia Nervosa

A. Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g., weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight less than 85 percent of that expected or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85 percent of that expected).

B. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight.

C. Disturbance in the way in which ones body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

D. In postmenarcheal females, amenorrhea; i.e., the absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles. (A woman is considered to have amenorrhea if her periods occur only following hormone, e.g., estrogen, administration.)

Specify type:

Restricting Type: during the current episode of Anorexia Nervosa, the person has not regularly engaged in binge eating or purging behavior (i.e., self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas).

Binge-Eating/Purging Type: during the current episode of Anorexia Nervosa, the person has regularly engaged in binge eating or purging behavior (i.e., self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas).

307.51 Bulimia Nervosa

A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following:

(1) eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within any two-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances

(2) a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g., a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating)

B. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior in order to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise.

C. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least twice a week for three months.

D. Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.

E. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of Anorexia Nervosa.

Specify type:

Purging Type: During the current episode of Bulimia Nervosa, the person has regularly engaged in self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas.

Nonpurging Type; During the current episode of Bulimia Nervosa, the person has used other inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as fasting or excessive exercise, but has not regularly engaged in self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas.

From the outset we were dismayed and astonished at the tremendous response to our publications. Thousands of women responded to our early work, readily revealing their binge/purge behavior. Their pain and shame were overwhelming as they bemoaned their wasted talents, interrupted relationships, and significant medical problems. The first edition of our book took five years to write. Without the hundreds of bulimarexic clients who educated us during that time, it never would have happened. The book is theirsa tribute to their trials and tribulations. From their strengths and moments of weakness, much valuable learning emerged. We are proud to have known and worked with these women and want to acknowledge their enormous talent and potential. Although the accounts they contributed are true, in every case we have changed their names and other details in order to protect their identities.

When the first edition was finally published in 1983, its reception surpassed our wildest expectations. Once again we received thousands of letters from women, thanking us and telling us that the book had given them hope. After reading it, many were able to reach out to therapy for the first time knowing that they were not alone, help was available, and success was possible. A significant number of women wrote that they had curtailed their binge/purge cycle on the basis of the book itself, without therapy. The self-help insights and strategies we outlined had helped them help themselves. Professionals wrote to us as well, and parents of bulimarexics thanked us for what they felt was the first compassionate treatment of their responsibilities and concerns.

Next page

New York London

New York London