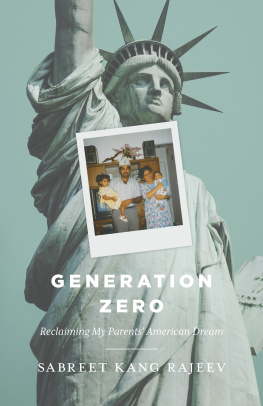

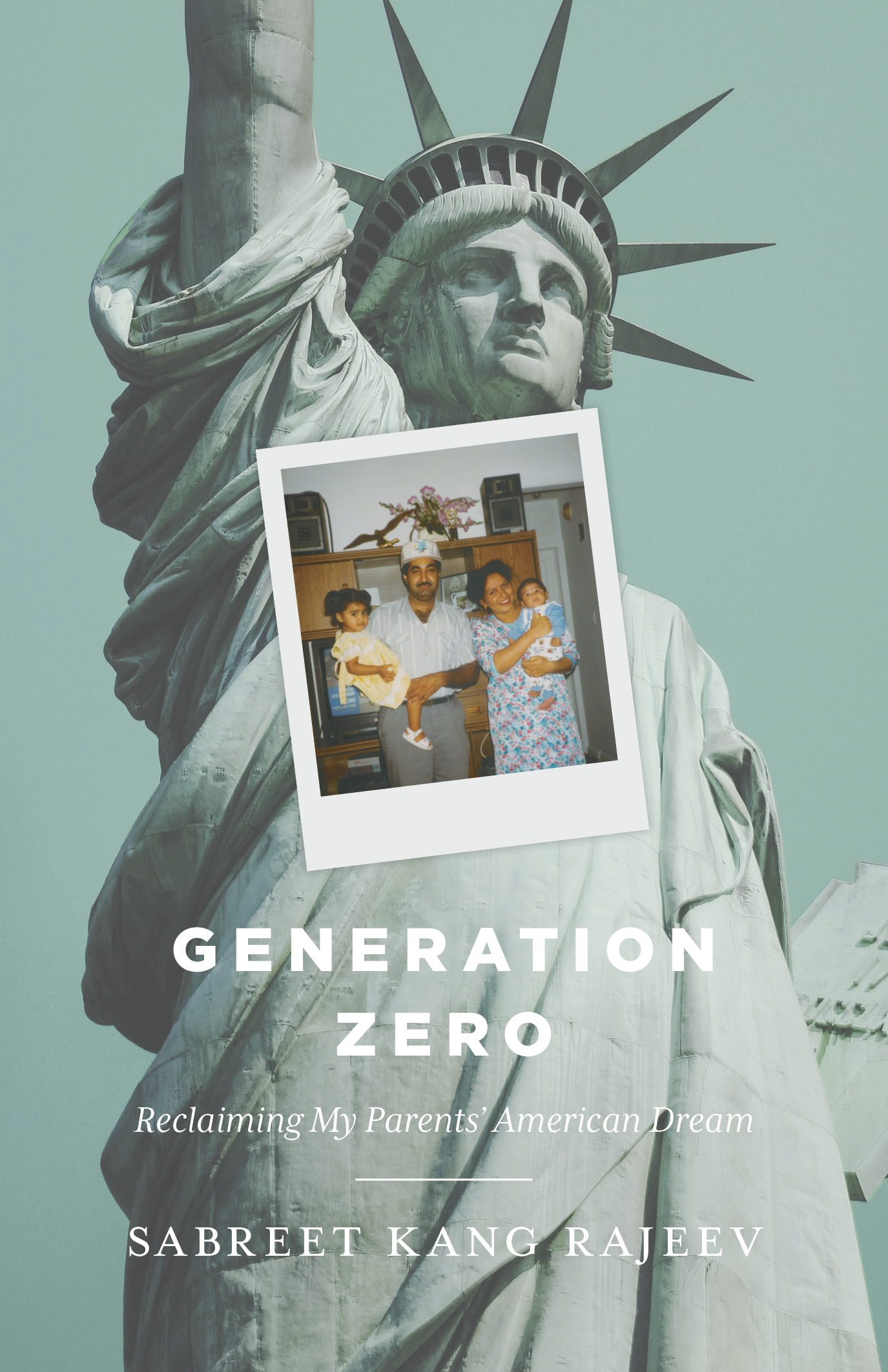

Copyright 2020 Sabreet Kang Rajeev

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-5445-1714-8

My parents

I have your prayers written all over me. Every word I speak, every thought I write will always start with you. Because of you, I am. Because I am, we are. Together and always.

My brother

Thank you for listening to me while becoming your own person at the same time. I know I am your older sister, but I am so proud of you. You are my pride and joy. You are so much greater than you may ever realize, and for everything you do, Ill always be your biggest fan.

My husband

Thanks for helping me realize that I can be understood. Your love for me never goes unnoticed. Without you, this book would have never been possible. I am a better woman because of you.

My chosen parents

Your kindness has no bounds. Thank you for loving me as if I had been with you since the day I was born. Your love shows me that humanity is good and how to love every being with open arms.

My unborn children

You deserve a model of love, not a martyr of love. I cant wait to love you for everything you were born to be.

My readers

This one is for you. I see you. I feel your pain. I know your suffering. I know our community can be better. Change starts with you.

Khudi ko kar buland itna, ki khuda bande se khud puche, bata teri raza kya hain?

Make yourself so selfless, that one day God comes down to ask youwhat is it that you desire?

Muhammad Iqbal

Introduction

April 25, 1990 was the day my father took down the picture of Guru Nanak Dev Ji from the walls of his one- bed room apartment in Flushing, Queens.

April 25, 1990 was also known as my birthday. I was born to an Indian taxi driver and his wife in Queens, New York. My father was so upset that I was born a girl, he literally became mad at God. He asked Waheguru:

Why did you give me a girl first? Ive never asked anything of you. The only thing I have ever asked in my life was to give me a firstborn son and you, you disrespected me.

Its not that my father didnt want a daughter. He was okay with the thought of having a girl; he just didnt want a daughter first , and he didnt want multiple daughters. One was enoughif she was the second child.

Having a daughter first meant she would not continue the family name. It meant that it would be more expensive to raise her in America. It meant that she would move in with her in - laws after she was married and would not take care of him and his wife in their old age. Being the eldest meant that she didnt have an older brother with authority to look after her as she grew up. It meant that she wasnt protected, and she was all alone. Having a daughter is not an economically rational decision in the South Asian community. The difference between being born a daughter in India versus America I could live. Being born a daughter meant I was unwanted. I was born without a voice. A voice that didnt matter because of my gender.

The truth is, the voicelessness that follows a female South Asian child from birth leaves millions of first - or second - generation women speechless, underestimating their potential and, ultimately, living a life filled with unprocessed trauma in their bodies. Being born into an immigrant family, the challenges an individual can face are often experienced in isolation. The collective trauma a family feels is silenced and understood as the necessary training wheels of assimilation. To further exacerbate our identities, there is no universal consensus on whether you can call yourself a first - generation or second - generation American to describe your familys or your immigrant experience.

According to the US Census Bureau, first - generation is the first family member to gain permanent residency in America. The Bureau also explains that first - generation can refer to individuals who were born outside of the United States. Second - generation refers to those with at least one parent who was born outside of the United States. Third - and fourth - generations include people who have two United States - native parents. Websters New World Dictionary states that first - generation refers to a person who is the first in a family to be born a citizen of the country their family has relocated to. To complicate things further, it also states that people who immigrated over can be considered first - generation Americans after they gain legal residence.

I thought looking up the definition would help me understand if I was worthy of being an American (because I still felt unworthy as an Indian due to my gender), but it did not. I realized that as an individual of an immigrant family, understanding my generational status was as complex as understanding my own identity. I felt isolated because of my gender, and growing up, the differences I saw between my family and other South Asian immigrant families felt peculiar. I felt secluded from the only acceptable identity I could relate to in America and found myself withdrawn from the family who was given to me at birth. The picture of Guru Nanak Dev Ji went up fourteen months later after my brother was born. Growing up, my life was a constant reminder of why I am less and my brother was more. It is hard to believe in gender - equality when the first story you remember as a child is that your gender made your father upset.

Why did my gender matter? There must be something wrong with me. I must be the most well - behaved daughter, so my parents can love me.

In reality, it doesnt matter how my parents felt about me; what truly mattered were the internal battles they were suffering from when I arrived in this world. My father didnt want a daughter first because he knew that my voice would be hard to hear in the South Asian community. My father didnt want a daughter first because it meant he had to keep going to forge his 401(k) retirement plan (my brother). My father and mother didnt feel Indian or American; they just felt like martyrs of their family, looking to provide a better future to their lineage. They didnt consider themselves as any generation.