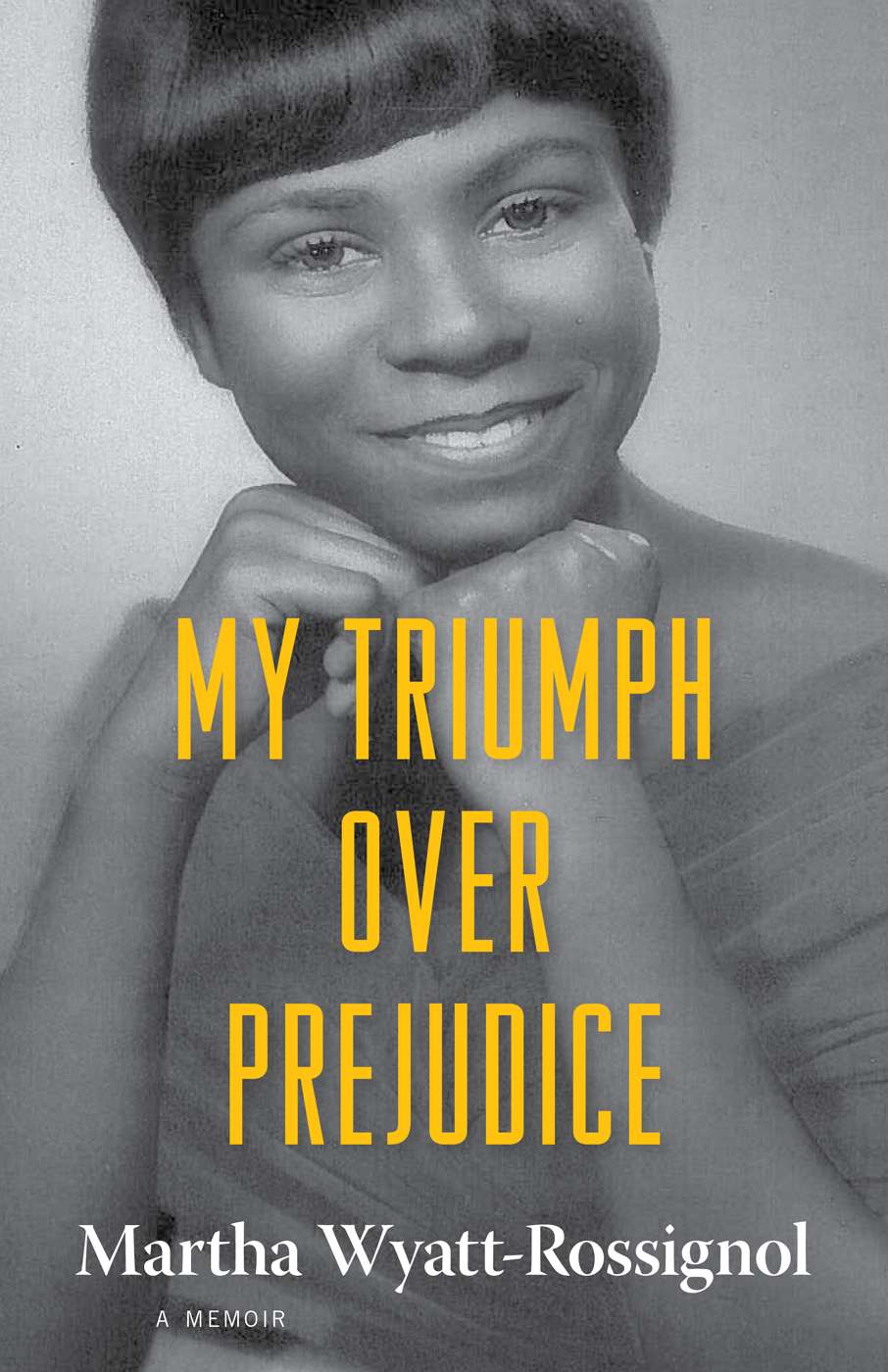

My Triumph over Prejudice

MY TRIUMPH OVER PREJUDICE

Martha Wyatt-Rossignol

A MEMOIR

University Press of Mississippi Jackson

Willie Morris Books in Memoir and Biography

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

All images courtesy the author.

Copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wyatt-Rossignol, Martha, author.

Title: My triumph over prejudice / Martha Wyatt-Rossignol.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2016. | Series: Willie Morris Books in Memoir and Biography | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015032209 (print) | LCCN 2016000140 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496806031 (hardback) | ISBN 9781496806048 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Wyatt-Rossignol, Martha. | African AmericansMississippiFayetteBiography. | African AmericansCivil rightsMississippiHistory20th century. | Race discriminationMississippiHistory20th century. | School integration--MississippiFayette. | MississippiRace relationsHistory20th century. | Interracial marriageMississippi. | Fayette (Miss.)Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Cultural

Heritage. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Discrimination & Race Relations. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / South (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV).

Classification: LCC E185.93.M6 W93 2016 (print) | LCC E185.93.M6 (ebook) | DDC 305.896/07307620830904--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032209

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

Acknowledgments

I want to thank my husband and soul mate of forty-plus years, Joseph A. Rossignol, for all of his patience and understanding while I pursued this dream of putting my lifes story into a book. Many times over, he read and reread my unfinished manuscript and helped me with the endless hours of research. I want to thank my dear friend Claudine Middleton for believing my life was worthy of a book and for giving me the idea to write about it; Jean Stoess of Reno, Nevada, for all the typing and editing she performed over a five-year period and for believing in me and my work; Walt Harrington, author of Crossings: A White Mans Journey into Black America, for pointing me in the direction of University Press of Mississippi for publication. I also want to thank my family and dear friends and I give them a heartfelt thank you for all their wonderful words of encouragement so that this manuscript could reach its potential. After years of writing and rewriting, I finally found the perfect editor to help me get it all togetherthank you, Linda Cashdan.

My Triumph over Prejudice

Figure 1. Martha and her sister

Growing-up Years

Fayette, Mississippi, my hometown, is located about seventy-five miles southwest of Jackson, not far from the Mississippi/Louisiana border. The little town, with its surrounding rural communities, is nestled between Natchez and Vicksburg, two old historic steamboat ports on the Mississippi River. When I was growing up there in the 1950s, the population of Fayette was less than two thousand residents, and it hasnt increased much since.

Both the town and the surrounding area were named for eminent political figures during the early nineteenth century, when the population consisted primarily of many slaves and their few masters. Jefferson County, then a collection of plantations and smaller farms, was named after our countrys third president, who had also been a slaveholder. Fayette was named after the honorary citizen and supporter of American independence, Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de La Fayette, who was taking a farewell tour of the region in the 1820s when the town was settled.

Even now, the downtown area has only two major thoroughfares, Main and Poindexter Streets, which cross at the very center of town. During my youth, a few ancient brick commercial buildings still existed, such as Freemans Department Store and the Guilminot Hotel, both dating back to the early 1800s. The Guilminot Hotel was then the only three-story building in downtown Fayette.

At the head of Poindexter Street stood the Jefferson County Courthouse, another old brick commercial building, where the lobby held an antique Coke machine and a WPA (Works Progress Administration) forestry display. Across from the courthouse was the Confederate Memorial Park, which could only be used by white people. The parks single monument was a statue of a Confederate soldier leaning on his rifle. During the warm months, older white people sat on benches in the park or milled around on the lush green grass under the big shade trees scattered throughout. During the cold months, the park remained deserted except for that lone stone soldier.

On its face, Fayette was a charming hamlet in a pretty part of the state. Fine old elms, pecans, magnolias, and beeches shaded the streets. The trees seemed to have held the same air captive among them for so long that they had acquired their own unique atmosphere. Like many southern towns, Fayette was quiet and peaceful and, during my early years, about as segregated as a town could be. I could clearly see that blacks were the majority, but it seemed as if blacks knew their place and the whites knew theirs, and no one crossed those invisible lines.

In the white section of town, the stately homes had remained unaltered for so many decades that they seemed frozen in time, throwbacks from another era. The homes had yards of beautiful flowers with well-manicured lawns, all maintained by black hands. What were known as the black neighborhoods, however, were situated in downtown Fayette across the tracks. The proverbial railroad tracks separated the two regions.

To visit a black family who lived downtown, one had to pass through the pristine white neighborhoods, with their rich foliage and cement sidewalks. Once a person was across the dividing line, the difference was literally like night and day.

Sometimes it seemed that the only inhabitants of the black neighborhoods were small children and old people, all sitting outside in the sweltering heat of summer evenings while the young adult workforce toiled across the tracks, and the rest found other places to entertain themselves. The homes varied in quality, from broken-down shacks with no running water to moderately nice-looking wood-framed ones. The beat-up old shacks undeniably predominated, and since there was no indoor plumbing, that meant many smelly outhouses. There were no paved streets or sidewalks in the black neighborhoods; the roads were all dirt or all gravel, or sometimes both, but the dust was forever flying free. In my memory, I can still feel the heat and dust clinging to my body and still smell those smelly old outhouses.

My brothers and sisters and I did not live in the black section of town, but in a rural area outside Fayette, a world far removed from the happenings of the town, a countryside consisting of woodlands and farmlands with all kinds of wildlife running free. About a third of all black residents in Mississippi, like our family, were engaged in farming. Some families had their own farms to live on, but there were quite a few, like us, who sharecropped. This was a system where a landowner allowed a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the profits. My father farmed cotton, corn, and sugarcane. When the cotton was harvested, it was taken to the gin to be sold and the profits were used to pay off the landlord. Profits from the corn and sugarcane were used to pay off debts as well. My father made molasses from the sugarcane and sometimes cans of molasses were given in lieu of money.

Next page