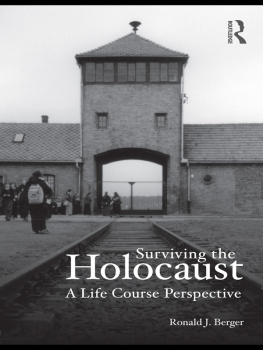

If we, the sons and daughters of those who

survived, will not remember their vanished

world, who will?

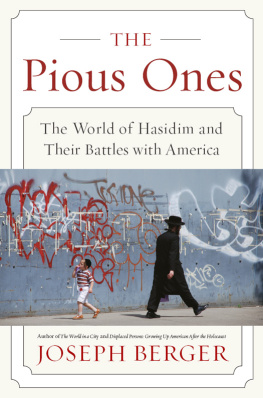

PRAISE FOR JOSEPH BERGER AND HIS

ACCLAIMED MEMOIR

DISPLACED PERSONS

With humor, compassion, and honesty, Displaced Persons portrays not only the vanished Europe of prewar Jewry but the vanished New York of Bergers childhood. Writing in an engaging, straightforward manner that conceals the elegance of his books underlying construction, the author moves back and forth between childhood memories and parental recollections.

Newsday

A book that, built of small, remembered moments, manages to create an engaging portrait of a profoundly complex world.

The New York Times

Gripping and beautifully written.

Library Journal

[A] vivid narrative, softened by a reflective somberness that is only occasionally tinged by nostalgia. By conjuring a complexly interwoven familial history that takes the reader across the boundaries of time, Berger lays the foundation for his thoughts about the larger immigrant experience.

Publishers Weekly

DISPLACED

PERSONS

GROWING UP AMERICAN

AFTER THE HOLOCAUST

JOSEPH BERGER

For Marcus and Rachel Berger,

and the steady heroism of all the refugees

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book germinated more than twenty years ago when I first sensed that my immigrant familys struggle with America and with the unrelenting grip of the Holocaust was a story worth writing about. After I decided to tell the story as straight as I could remember it, and not disguise it as fiction, many people gave me invaluable help. Joel Fishman, my literary agent, helped me shape some stray chapters and an outline into something closer to a book. Eva Fogelman and her husband, Jerome Chanes, offered inspiration; Willie Helmreich, some necessary research; and Menachem Rosensaft, Sam Norich, Ben Meed, and Donna Cohen, the sense of a larger community. Friends such as the late Norbert Wollheim, the late Barry Kwalick, Esther Hautzig, Dan Cryer, Jerry and Eva Posman, Roberta Hershenson, Ira and Joyce Goldstein, Jules Bemporad, Nancy Albertson, Robin Gaines, Stacey Fredericks, Alon Gratch, Regina Schwartz, David Aftergood, Stuart and Susan Knott, and Ellen Abrams and my brother, Josh, sister, Evelyn, and brother-in-law, Ivor Shapiro, provided the needed cheerleading.

The book would have been poorer in every way without the passionate enthusiasm, literary sensibility, and plain good sense of my editor at Scribner, Jane Rosenman. Her assistant, Ethan Friedman, took care of important details with grace and cheer. Nancy Miller, my neighbor, friend, and editor on my first book, helped the book find its publisher and let me feel, as I kept on writing, that this was a project worth undertaking. Most of all, my wife, Brenda, gave me insight and understanding during long car rides and late-night talks and she and our daughter, Annie, were more than tolerantthey were loving and generousin letting me take Sunday and weekday mornings to bring the story to light.

DISPLACED

PERSONS

INTRODUCTION

A few years after I joined The New York Times, its editors and reporters were asked to attend a presentation on the newspapers future given by Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr., who at the time was being groomed to become publisher. I arrived for work carrying a brown paper bag with a container of coffee and a seeded roll, thinking Id have some time to enjoy breakfast at my desk before heading upstairs to the publishers suite.

Ive always enjoyed seeded rolls because when I was a child we would have them on Sunday mornings for breakfast, one of the few meals during the week that we shared together as a family. My parents were Polish-Jewish refugees who had survived the Nazi slaughter and immigrated to America, and throughout my childhood both of them had worked long days in dreary factories. A weeknight supper was usually a slapdash affair, with my father and sometimes even my mother absent. So Sunday-morning breakfast was a sanctified time.

Even at six and seven years old, I enjoyed walking the four or five blocks, savoring the warmth of the mornings sunshine, to the Cake Masters bakery on upper Broadway to fetch those rolls as well as a seedless rye bread and a few fruit Danishes that my nervously economical parents allowed themselves as a treat. Before entering the bakery, I would press against the glass display window and find myself hankering for one of the marzipan potatoes coated with a sprinkling of cinnamon and cocoa. Maybe next Sunday, I told myself, I would get my parents to splurge for one. Inside, the shop was snug and teeming, with the spirited air of men and women on the verge of indulging in some especially tasty food, in this case the bakerys rich confections, arrayed like the crown jewels in a sumptuous glass counter. I would wait my turn, and when the European saleslady in a white apron smudged with powder and jelly gestured to me, I recited my parents order like the rote prayers I was learning in yeshiva.

A round rye bread without seeds, sliced, four seeded rolls, and two blueberry Danishes, I would chant, anxious that I not forget anything on the list.

When I returned with the booty, we would sit around our tableI still remember the chill of its white enameled metal topand devour our rolls and bread, perhaps some slivers of schmaltz herring and a cottage cheese salad with radishes, scallions, cucumbers, and tomatoes, and wash the meal down with cups of instant coffee. Sometimes we laughed, sometimes we bickered, but we were together. It was evident in their glimmering eyes that my orphaned parents relished the sight of our togetherness as a family as if there were no sweeter gift imaginable. And I reveled in their delight.

So this roll I was about to have at the Times would no doubt be made tastier by those pleasant associations. In the elevator I saw that my colleagues were already heading up to the fourteenth-floor suite and I realized I had gotten the time wrong. I would not have time for breakfast. I dashed to my desk, took off my coat, and, snatching the bag of roll and coffee, caught the elevator upstairs. Although by then I had worked for the Times for four years, mostly as a writer on religion and education, I had never been to the publishers floor. I followed a stream of latecomers through the suite and up a winding staircase to a large and elegant penthouse lounge. I was struck by the stately cherry woodwork, the framed antique maps and sketches of ocean liners, the soft carpets. I did not want to spill coffee on these carpets. That would reveal that I really did not belong here.

The penthouse room was filled with more than a hundred reporters and editors, including management people like Max Frankel, Warren Hoge, and Dave Jones, who were sitting in the club chairs at the front. I felt an air of formality unusual even for the distinctly formal Times of those years. Almost all the men had their jackets on. I spotted an empty seat two thirds of the way toward the back and, still holding my bag of coffee and the seeded roll, I slipped in.

Young Sulzberger, in shirtsleeves, crisply pressed trousers, and bright red suspenders, was talking about how the Times had teetered on the edge of financial failure in the early 1970s but had emerged gloriously by investing in a new printing plant and boldly starting several sections that invigorated advertising. The Times once again needed to expand. It was building a $400 million plant that would allow it to produce a bigger daily paper and use color for almost every section. When all the changes were in place, Sulzberger assured us, the

Next page