To my parents, Marcus and Rachel Berger,

who bequeathed to their children the flavor of the

lost shtetls and ghettoes of Europe

There are two levels in the study of Torah, Torah of

the mind and Torah of the heart. The mind cogitates,

comprehends and understands; the heart feels.

I have come to reveal Torah as it extends

to the heart as well.

If the Bible didnt show us the weaknesses, the

vulnerabilities, the sins of our heroes, we might have

deep questions about their true virtue.

Baal Shem Tov

CONTENTS

W e throw around the term crisis of faith so casually, applying it to artists, politicians and bankers, not only tormented religious souls, that it has become a clich of our times. Yet imagine what a crisis of faith must have been like for a man named Shulem Deen.

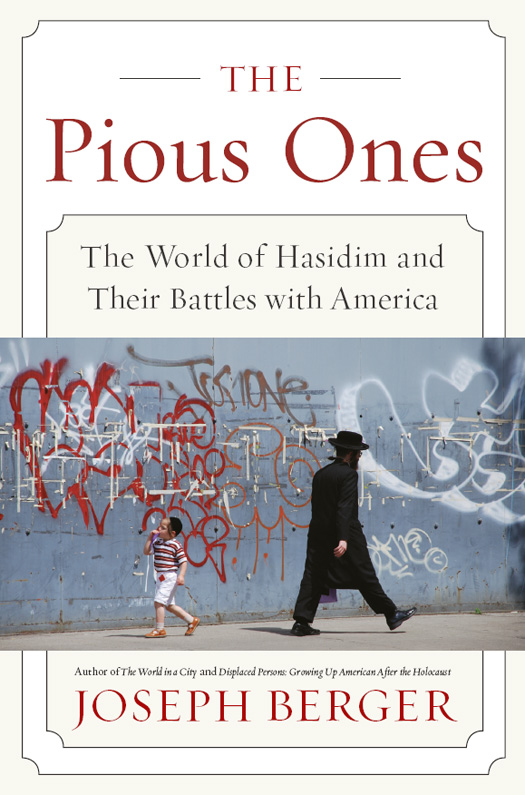

Deen had grown up a Hasid, a member of a rigorously Orthodox subculture of Judaism. Most strangers recognize Hasidim by the black suits, black hats and broad beards of the men and the wigs and the enveloping outfits of the women but know little else about these people. What many outsiders do not appreciate is how all-encompassing a life Hasidism is, not just a faith for a Saturday or Sunday morning, but one that governs almost every waking hour and virtually every activity of daily lifewhat one reads and studies, who one marries, how many children one has, how one spends much of a day, even how one goes about having sex.

So when doubts about the literal truths of the Bible and other tenets he had been taught virtually round-the-clock since childhood led to his disenchantment with the restrictive Hasidic life, he had to wrestle with what leaving the fold would mean for his marriage, his intimacy with his children, his friendships, his work, his social life, what he ate, what schooling he would give himself and his family. Yet he could no longer be a Hasid, live what he felt was a consuming lie.

It started becoming more and more ludicrous, he told me. I began to realize I didnt want to live in a world I so fundamentally disagreed with. It was something I couldnt do.

Deen did leave and for the most part won the liberty to think and act for himself that he sought, but his doing so had many of the consequences he feared. His marriage has dissolved and four of his five children refuse to see him.

In studying the Hasidim, which I have often done in more than 40 years as a journalist, I could not help but be struck by the bittersweet, paradoxical outcome of Deens journey. Yet I also had to balance his tale against many other stories Id learned, many of them far more ennobling of the Hasidic lifestyle than that of Deens. And the basic mysteries endured: How do people in an age that venerates personal freedom take on a life of so many commands and restrictions? What is it about that life that draws them and holds them in its grip as firmly as iron filings to a magnet? Why does it come into conflict so often with the wider society? Why do I hear so many intelligent people, especially Jews, revile Hasidim, accusing them of holding themselves above American laws while exploiting those same laws for their own sustenance?

I felt in undertaking a book on the Hasidim that many Americans are curious about this tribe of people that increasingly presses itself on societys consciousness not just by its offbeat, colorful presence but by its rapidly growing numbers and influence. In a place like New York City, where Hasidim are a forceful, expanding minority, almost every week seems to bring another encounter with the ways of Hasidimsome profoundly troubling like Shulem Deens story, some enchanting and ennobling. The story of Leiby Kletzky, chilling as it was, gave people a deeper acquaintance and respect for Hasidim.

In the summer of 2011, Leiby Kletzky, an eight-year-old boy, asked his parents if he could walk home from day camp alone for the first time. They assented and he set out on his own through his Hasidic neighborhood of Borough Park in Brooklyn. But he soon got lost and stopped a stranger to ask for help. The stranger, Levi Aron, a bearded thirty-five-year-old hardware stock clerk with an oddly out-of-joint facial expression beneath a newsboys cap, lured the boy into his beat-up Honda, bizarrely drove him 50 miles north of the city to a cousins teeming and tumultuous wedding in the Hasidic hamlet of New Square, then drove him back to his apartment in Brooklyn. The next day, he drugged and suffocated Leiby, killing him, then sliced up his body and stored his feet in his refrigerator while depositing the rest in a suitcase and throwing that into in a Dumpster. The security camera film of little Leiby, a yarmulke crowning a face with too-large horn-rimmed glasses and long, dark sidelocks, as he nervously waddled along on a sidewalk moments before he was abducted, haunted many who saw it, none more so than parents struggling with the amount of independence to give to their young children.

In the days after the crime, New Yorkersand indeed much of the nation, since the murder of the missing boy was on all the networkslearned much about the Hasidic community. It was astonishingly zealous, cohesive and well organized, with hundreds of rumpled, bearded men streaming in from around the neighborhood and even from their summer bungalows in the Catskills to search single-mindedly for a boy they did not know. And when a funeral became sadly necessary after the boys body was discovered, 10,000 people showed up at nightfall of the same day, spilling out of a synagogue to listen to an intense, heartbreaking eulogy, the men in a jostling, swaying swarm surrounding the coffin, the women clustered on the margins in long-sleeved dresses despite the near 90 degree heat. The Hasidic community, those unfamiliar with them were able to deduce, was impressively prolific, with families bulging with six and seven children and some with more than a dozen, in an era when most American couples married late into their 20s and had a child or two.

While most Americans had a monolithic view of the Hasidim as insular in their approach to outsiders, and spartan and anachronistic in their lifestyles, many viewers and readers who followed the Leiby Kletzky story closely were surprised at the variety within the Hasidic world. There were dozens of sects with different attitudes toward mainstream society, even distinctive styles of clothing. Some Hasidic men wore the equivalent of black sombreros and others homburgs; some women preferred wigs while others covered their hair with a kerchief. It turned out that neither Leiby nor his killer was Hasidic. Leibys family was ultra-Orthodox but not Hasidic because it did not venerate a single grand rabbi the way most of the searchers did. Levi Aron did not even merit an ultra. He came from a plain-vanilla Orthodox family though his father worked in the nationally famous camera and gadget emporium of B&H, which, to the surprise of those bearing views of Hasidim as antediluvian, is owned, managed and staffed largely by Hasidim.

And Americans learned that despite the close-knit nature of the community, which was genuine, Borough Park was increasingly reaching out to the mainstream, most relevantly for help with troubled individuals. True, it had historically sought to deal with problems within the communitythrough its rabbis and rabbinical courtsbut that was slowly changing, too, most prominently as it, like the rest of society, coped with the problem of sexual abuse of minors (though it was never proven that Levi molested Leiby before he killed him). Dozens of cases of abusive teachers, camp counselors, merchants, even rabbis that had been secretly dealt with or hushed up within the community have been turned over to officials like the district attorney in Brooklyn.