Captive Nation

JUSTICE, POWER, AND POLITICS

Coeditors

Heather Ann Thompson

Rhonda Y. Williams

Editorial Advisory Board

Peniel E. Joseph

Matthew D. Lassiter

Daryl Maeda

Barbara Ransby

Vicki L. Ruiz

Marc Stein

The Justice, Power, and Politics series publishes new works in history that explore the myriad struggles for justice, battles for power, and shifts in politics that have shaped the United States over time. Through the lenses of justice, power, and politics, the series seeks to broaden scholarly debates about Americas past as well as to inform public discussions about its future.

More information on the series, including a complete list of books published, is available at http://justicepowerandpolitics.com/.

This book was published with the assistance of the John Hope Franklin Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America.

Set in Calluna by codeMantra. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

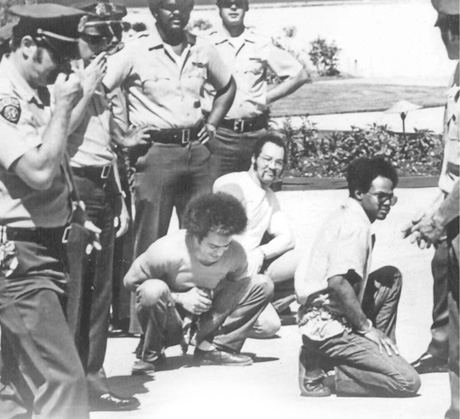

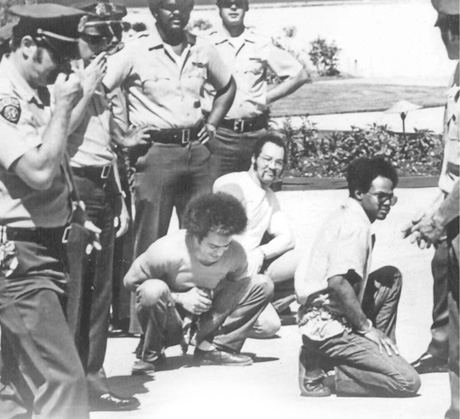

Jacket illustration: The Soledad Brothers being transported from court, 1970.

Photo by Dan ONeil.

Complete cataloging information can be obtained online at the Library of Congress catalog website.

ISBN 978-1-4696-1824-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-1825-8 (ebook)

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

Part of chapter 5 has been reprinted with permission in revised form from Carceral Migrations: Black Power and Slavery in 1970s California Prison Radicalism, in The Rising Tide of Color: Race, State Violence, and Radical Movements across the Pacific, ed. Moon-Ho Jung (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014), 21336.

ALSO BY DAN BERGER

Letters from Young Activists: Todays Rebels Speak Out (coeditor, 2005)

Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity (2006)

The Hidden 1970s: Histories of Radicalism (editor, 2010)

The Struggle Within: Prisons, Political Prisoners, and Mass Movements in the United States (2014)

IN MEMORY OF

Marilyn Buck (19472010), Dara Greenwald (19712012), and Stephanie M. H. Camp (19682014), loving and beloved friends, dedicated dreamers, visionary artists who gave us all a glimpse of a more perfect world.

And for those who, in their tradition, create with purpose and passion.

So it was that, to the Negro, going to jail was no longer a disgrace but a badge of honor. The Revolution of the Negro not only attacked the external cause of his misery, but revealed him to himself. He was somebody. He had a sense of somebodiness. He was impatient to be free.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., Why We Cant Wait (1963)

At first, you were coons, darkies, colored, niggers, Negroes; then we became crime in the streets.

AUDLEY QUEEN MOTHER MOORE, interview (1972)

They tell us that the prisons are overpopulated. But what if it were the population that were being over-imprisoned?

MICHEL FOUCAULT, press conference (1971)

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

The Jailhouse in Freedom Land

CHAPTER TWO

America Means Prison

CHAPTER THREE

George Jackson and the Black Condition Made Visible

CHAPTER FOUR

The Pedagogy of the Prison

CHAPTER FIVE

Slavery and Race-Making on Trial

CHAPTER SIX

Prison Nation

EPILOGUE

Choosing Freedom

Illustrations

A February 11, 1970, rally for imprisoned Black Panther leaders in San Francisco

Black Panther Party cofounder Huey P. Newton at a press conference following his release from prison in August 1970

The Soledad Brothers: John Clutchette, Fleeta Drumgo, and George Jackson, ca. 1971

Fay Stender at a protest for George Jackson at the gates of San Quentin, October 1970

The Reverend Cecil Williams speaks at a rally to support the Soledad Brothers, ca. 1970

George Jackson being led to court, ca. 1971

Angela Davis and Jonathan Jackson at a rally for the Soledad Brothers, 1970

Jonathan Jackson at the Marin County Courthouse on August 7, 1970

James McClain points a revolver at police while holding a shotgun taped around the neck of Judge Harold Haley on August 7, 1970

A mural depicting Jonathan Jacksons raid on the Marin County Civic Center

The San Quentin Adjustment Center on August 21, 1971, with cell assignments marked

George Jackson lies dead in the San Quentin courtyard on August 21, 1971

San Quentin Adjustment Center cell 1AC-6 on August 21, 1971

Pallbearers load George Jacksons casket, draped in a Black Panther flag, into the funeral car, August 28, 1971

The gun that authorities alleged was smuggled to George Jackson

Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee at a preliminary hearing, ca. 1971

Ruchell Magee raises a shackled, clenched fist during his trial, ca. 1971

Angela Davis leaving court with attorneys Haywood Burns and Howard Moore, June 1972

Angela Davis speaks at a rally after her release, ca. 1972

San Quentin 6 defendants Fleeta Drumgo, Hugo Pinell, and David Johnson stage an impromptu sit-in at San Quentin in July 1975

The San Quentin 6 on trial, ca. 1976

Former San Quentin 6 defendants Bato Talamantez, David Johnson, and Willie Sundiata Tate speak at a rally with Inez Garcia at the San Francisco Civic Center, November 1976

Arm the Spirit newspaper

The Fuse magazine

Preface

I first went to prison at age nineteen. It was the spring of 2001, and the United States had passed a dystopic milestone one year earlier: more than two million people were now incarcerated in prisons and jails around the country, a higher rate of incarceration and a higher number of people in prison than anywhere else on the planet. Unlike the thousands of other teenagers who went to prison that year, however, my trip was voluntary and brief. I was just a visitor. I was a sophomore in college, interested in social movement history and just beginning to get passionate about school. Ninety miles from my small-town college campus was a maximum-security federal prison that held a former member of the Black Panther Party who had been incarcerated since 1973. My first time inside, I tried to notice all the detailsthe gun towers surrounding the prison and the perennials cracking through the sidewalk leading up to it, the concertina wire guarding us and the vending machines feeding us. It was just another high-tech institution in our dotcom worldexcept it wasnt that at all.

Once inside, we had a grand time laughing, talking politics, and eating overpriced chips and popcorn. During my visit, I learned about life in the Black Panther Party and life in a federal penitentiary. I was learning, in fact, a deeper history of the intersection of black protest and state repression. It was the story not just of state violence but of alternate worldviews, a fact made plain by the letters Veronza Bower sent me, which were dated ADJ. The first letter I received from him was dated 30 years 231 days ADJ AKA 22 March 2001. I learned that ADJ stood for After the Death of Jonathan Jackson, the seventeen-year-old brother of radical prisoner and author George Jackson. Both Jacksons died bloody deaths at the hands of the California prison system, Jonathan in an August 1970 attempt to free three prisoners from a Marin County trial and George a year later during a takeover of San Quentins solitary confinement unit. After Jonathan was killed, George wrote that his brothers death marked a new phase of timea tradition that some dissident prisoners continued to honor more than thirty years later. At the time, I knew little about George Jackson, but I was beginning to learn the parallel cosmology of prison organizing. Because the prison sought to control all aspects of life, dissident prisoners rewrote the taken-for-granted elements of everyday life. They politicized things typically taken for granted, whether through marking time or through identifying as New Afrikans to locate their identity within the complex social, political, historical, spatial, and discursive factors that have shaped black life in the United States in, through, and despite confinement.

Next page