HUEY P. NEWTON THE RADICAL THEORIST

HUEY P. NEWTON THE RADICAL THEORIST

Judson L. Jeffries

www.upress.state.ms.us

Copyright 2002 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jeffries, J. L. (Judson L.).

Huey P. Newton : the radical theorist / Judson L. Jeffries.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-57806-432-5 (alk. paper)

1. Newton, Huey P. 2. Black Panther PartyBiography. 3. African AmericansBiography. 4. RadicalsUnited States Biography. 5. Newton, Huey P.Political and social views. 6. Black powerUnited States. 7. African AmericansPolitics and government20th century. I. Title.

E185.97.N48 J44 2002

322.42092dc21

[B]

2001046780

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

This book is dedicated to my brother, the late

Roger J. Jeffries, a fifth-degree black belt who

began teaching me the art of self-defense

at a very young age, thereby instilling in me

confidence, courage, determination, and a sense

of honor that has made me what I am today.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The 1960s represent one of the great epochs in American history. That period involved widespread social upheaval and continued protest on the part of those Americans who considered themselves disenfranchised from the American mainstream. Through it all, black Americans emerged as the principal actors for political, social, and economic change. The ethic of resistance to oppression as the basis of making strong appeals for justice has always been a part of the black protest tradition.

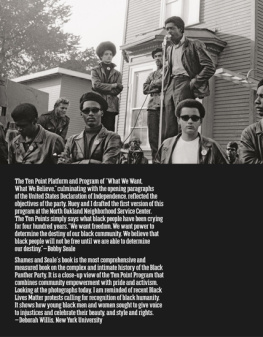

Unlike in the 1950s though, there emerged out of the black community a number of militant groups that turned their backs on the philosophy of nonviolence that so permeated the previous decade. Leaders of those earlier organizations tended to think of racism as some type of moral defect in the conscience of white America. For them, America needed a cleansing of its conscience, a moral reform. Charles Evers, Mississippi field director for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), once said: White Americans are sick and their minds are twisted. Weve got to straighten them out and heal them. Conversely, according to these newly founded militant groups, white America had no conscience, hence it was fruitless to talk about moral reform. What morality? This country aint got no morality! was a common theme in the speeches of Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture). In the minds of these militants, what was needed was power to bring about the redistribution of wealth. Among these groups were the Congress of African Peoples, Us, the Revolutionary Action Movement, the Deacons for Defense and Justice, and the Republic of New Africa. But none of these groups commanded the attention and captured the imagination of the American people as did the Black Panther Party.

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, as it was originally called, was established in Oakland, California, in October 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby G. Seale. The Panthers

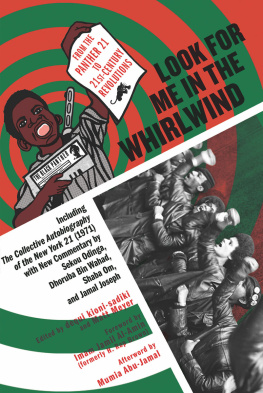

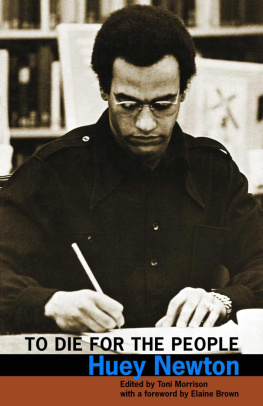

In some sense the Black Panther Party considered itself the heir apparent to Malcolm Xs short-lived Organization of Afro-American Unity, calling for armed self-defense and black self-reliance. Newton maintained that the Black Panther Party exists in the spirit of Malcolm. Even though the organization was cofounded by Seale and Newton, Newton was and is recognized as the unquestioned leader of the Black Panther Party. Newton was the groups minister of defense and chief ideologist. Approximately thirty books have been written about the Black Panther Party since its founding. However, none of them presents or examines the ideas of its leader in an expansive or systematic fashion. This book attempts to fill that void. It is not a biography but rather a work that presents and to some extent analyzes the political thought of Huey P. Newton. Although some of the ideas expressed throughout the Partys existence came about as a result of a collective effort on the part of Black Panther leaders like Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, David Hilliard, Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown, and others, Newton wrote many of the organizations theoretical treatises and presented them to the general public. Party members credit Newton with advancing many of the ideas discussed in this book.

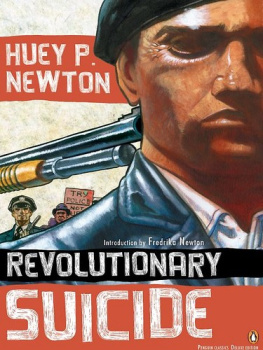

In terms of literary quality, Newtons pronouncements lack the rhetorical eloquence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.s, are devoid of the fire and intensity present in the writings of Malcolm X, and lack the academic rigor that distinguish W. E. B. DuBoiss works. However, as political scientist John McCartney has noted, Newton was, without a doubt, the most forceful, best-known and most ambitious theorist-practitioner of the Black Power Movement.

In 1989, Newton was shot and killed, allegedly over a drug deal gone bad. It was well known that Newton had developed an addiction to drugs years before his death. The irony is that Newton was well aware of the perils of drugs and the adverse impact drugs were having on the black community. In a 1978 interview, Newton, talking about heroin, said, The trafficking of heroin is one of the greatest dissipating factors in the black community. It is an evil that has to be driven out of our community.

One could argue that Newtons later acts of imprudence provide his critics with a convenient excuse to disregard him as a scholar and author and an important political thinker. After all, whenever one picks up a mainstream textbook that discusses the great thinkers of various times, black intellectuals and scholars are almost always conspicuously absent. When white political theorists convene at their annual meetings to present papers, scholars and intellectuals such as Anna Julia Cooper, W. E. B. DuBois, Oliver Cromwell Cox, Maria Stewart, Edward Blyden, CLR James, or even Martin L. King Jr. are seldom the subject of these essays. When blacks are the subject of scholarly endeavors, their work is oftentimes belittled for lack of originality and rigor. Francis S. Broderick wrote of DuBois: none of his books except The Philadelphia Negro is first-class. His writings on African culture, history, and politics all possess some information, but nothing which indicates the mind or hand of an original scholar. This seemingly racially motivated critique has a long-standing tradition within the white scholarly community. Is it because many whites believe that there are no black theorists worthy of recognition or study? Scholars of the Enlightenment period put forth the theory that the ability to reason is what separated humans from animals. As far as they were concerned, blacks showed no signs of being able to think rationally; therefore, they must be animals or, at most, some form of primitive creature. The rationalization that blacks were subhuman was practical, for to acknowledge blacks as men and women would be tantamount to admitting that whites did not behave as Christians. Georg Wilhem Friedrich Hegel, one of the most important political philosophers of the modern era, denied that Africa has any history because blacks In a major essay, Of National Characters (1748), the esteemed David Hume discusses the Characteristics of the worlds major divisions of human beings. In a footnote added in 1753 to his original text, Hume posited with authority the fundamental identity of complexion, character, and intellectual capacity:

Next page