Contents

Guide

Copyright 2019 by Kimberly Cox Marshall

Introduction copyright 2019 by Steve Wasserman

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the original hardcover edition as follows:

Names: Cox, Donald, 1936-2011, author.

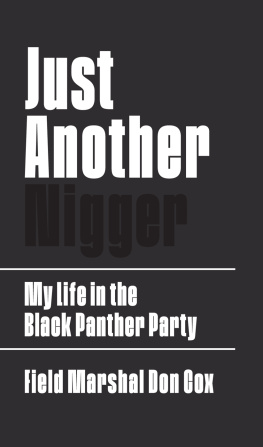

Title: Just another nigger : my life in the Black Panther Party or use what you got to get what you need / Don Cox.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004946 | ISBN 9781597144599 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781597145558 (e-pub)

Subjects: LCSH: Cox, Donald, 1936-2011. | Black Panther Party--History. | African Americans--Missouri--Biography.

Classification: LCC E185.615 .C692 2018 | DDC 322.4/20973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004946

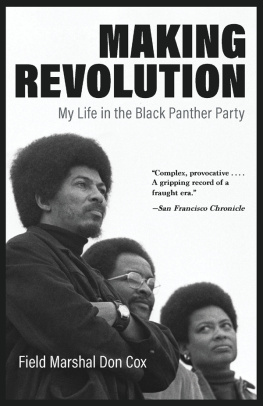

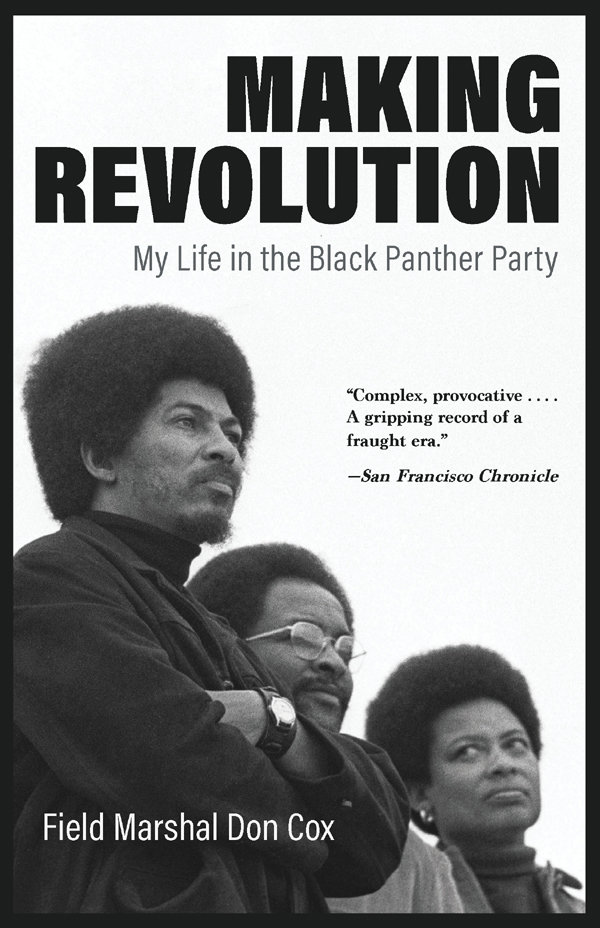

Book and Cover Design by Ashley Ingram

Cover Image Stephen Shames/Polaris

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In my own country for nearly a century

I have been nothing but a nigger.

W. E. B. Du Bois

Contents

Foreword

Kimberly Cox Marshall

PROMISE MADE, PROMISE KEPT. I didnt know that when he put his manuscript in my hands and made me promise to publish it after he passed, that would be the last time I saw him. But now its done: promise made, promise kept.

My first memories of Daddy are of the time we spent with his family. It seemed like almost every weekend we were either at his sister Irenes or his aunt and uncles in Mountain View, about forty miles south of San Francisco, where we lived. His two sisters that lived out here in California, Irene and Mary Jane, doted on their younger brother, and that affection trickled down to me. How I loved my aunts! When I would visit, they would always have grapes with the skin peeled off, because Donalds daughter didnt like the skin. Every year until she couldnt, my Aunt Irene sent me two dollars, and then five dollars (for inflation, as she said) for my Birthday Ice-Cream Cone. They were like that until they passed.

And then there was Daddy himself.

I have so many good memories of us together. I remember him picking me up from the San Francisco School of Ballet, and there he would be in his Austin-Healey, always with the top down. He would drive through Golden Gate Park so I could sit in the back and throw kisses like I was Miss America. When I would say I was going to hang out on the beach, like I saw girls doing in the movies, he never said anything to stop me. I realize now that I was never going to be in the San Francisco production of The Nutcracker, I wasnt going to be Miss America, and most beaches had signs to keep me and my kind out, but Daddy never told me I couldnt do any of those things. For him, I had no limitations.

I also loved our weekend outings to the movies as I got older and he started getting political. I didnt recognize it then, but I do now: all of the movies were war movies. And as it turned out, watching all those tactical storylines paid off for me, and for him. I remember one time, during the years Daddy was in the Black Panther Party and I was going to private school in the Richmond District of San Francisco, there was a man known for accosting and molesting young girls in the area. That same man had followed me to school one day, and as soon as I was inside the building I called my family to tell them about it. A week later, as I was getting off the bus, there was Daddy waiting at my stop, dressed in his old Brooks Brothers suit and with his afro cut off. He gave me a look that said I should be quiet and opened his jacket to show me he was carrying. I got off the bus and went on ahead to walk the five blocks to school, and although Daddy was nowhere to be seen, I knew he was watching my every move.

Another time, when I was going to a Lutheran school, I wore my hair in a curly afro one day. How proud I wasuntil I got to school. The principal told me my hair looked a mess. I promptly called Daddy, and I dont remember what I told him, but the next thing I knew, here comes Daddy and about four or five Panthers looking fine and sharp in all-black turtlenecks, pants, leather coats, and berets. I never heard my Daddy raise his voiceI think I would have crapped in my pants if I didand when he spoke, he always spoke eloquently and softly and looked you directly in the eyes. For people who didnt know him, that alone could make them crap in their pants. I didnt hear what he said to the principal that day, but at the end of the year I left that school for good.

When I was ten or twelve years old, we lived down the hill from Alamo Square, and whenever I heard the helicopters, I would ride my bike looking for friends to come with me to the Panther office. We would ride to the top of the square to see if there were more than two eyes in the sky (helicopters), and if so we would ride our bikes to the Panther officeus dumb kids figuring the cops wouldnt shoot if there were kids around.

Here are some things I learned from Daddy:

My family taught me empathy, and Daddy was never one to shy away from showing it.

I loved marching with him in the CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) protest marches of the early sixties, and even though I was probably too young for it, I was exposed to many important things there.

During events put on for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, in 2016, I had men search me out to tell me that if it wasnt for Daddy they dont know where they would have ended up in lifethat he taught them so much.

He and my mother also taught me we have to invest in our young people, as they are our future.

Among all the things Im grateful for, one thing that stands out is this: I got to meet Stokely Carmichael (later, Kwame Ture) and his wife, Miriam Makeba, when they came to dinner at my grandparents house. I didnt realize it at the time (but I so cherish the memory now) that I was being taught about apartheid literally at the knee of Mama Africa. I remember she told me a story of how her brother wasnt legally allowed to ride his bike at night in their native South Africa because they had to come indoors when it got dark. I was about twelve at the time and could hardly believe my ears, such a story was so foreign to my experience. I always remember that conversation because everyone around me got so quiet. I can imagine where those memories took my grandparents and great-grandmother, who were from the South.

No matter how proud I was of Daddys activities, though, there was also a flipside. Schoolmates stopped playing with me and inviting me to their parties because of Daddys politics. A relative that had the same last name changed it for a time so they would not be associated with our family. Our phone was tapped. The eye in the sky would flash its spotlight into my bedroom window, and sometimes we would come home and find the FBI surrounding the house or Daddys carthe GTO he drove to Nevada to buy guns. My mother would literally shoo the police away like flies. I heard once Daddy had even used a dead babys death certificate to get a fake passport. When things started to go bad in the party, there were two kidnapping attempts on me, and one night a woman came to our house to kill my mother, brother, and me. We can only thank goodness that she was so high she couldnt go through with it. My mother talked her down and she left. By then things were so bad that Daddy left the United States and started his life in exile. I would not see him for thirteen years, and I communicated with him only about five times before I saw him again in 1984.