BLACKS IN THE DIASPORA

| FOUNDING EDITORS | Darlene Clark Hine |

| John McCluskey, Jr. |

| David Barry Gaspar |

| SERIES EDITOR | Tracy Sharpley-Whiting |

| ADVISORY BOARD | Kim D. Butler |

| Judith A. Byfield |

| Leslie A. Schwalm |

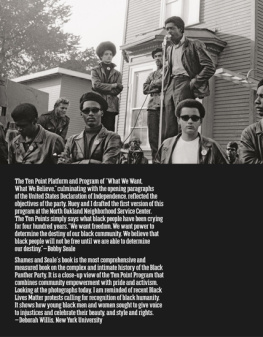

COMRADES

COMRADES

A LOCAL HISTORY OF THE

BLACK

PANTHER

PARTY

EDITED BY

JUDSON L. JEFFRIES

Indiana University Press

Bloomington and Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail iuporder@indiana.edu

2007 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by anyinformation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from thepublisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissionsconstitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of AmericanNational Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for PrintedLibrary Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Comrades: a local history of the Black Panther Party / edited by Judson L. Jeffries.

p. cm. (Blacks in the diaspora)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-34928-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-21930-5 (pbk.:

alk. paper) 1. Black Panther PartyHistory. 2. United StatesHistory, Local. 3.

African AmericansPolitics and government20th century. 4. African Americans

Economic conditions20th century. 5. African AmericansServices forHistory

20th century. 6. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 7. United

StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. I. Jeffries, J. L. (Judson L.), date

E185.615.C654 2007

322.420973dc22 2007013592

1 2 3 4 5 13 12 11 10 09 08

This book is dedicated to all those

Panthers and community workers

who served on the ground and

whose work and deeds have

heretofore gone unnoticed by

academics and laypersons alike

R egardless of their public image, the Black

Panthers need to be understood. I have worked intensively with the

Panthers for three years and have been amazed at how few

People, black or white, have made any effort

To understand why there is a Panther Party. In the few years I have

worked with the Black Panthers, I have become convinced that

there is a cathartic and therapeutic element

In this revolutionary force.

I have seen their anguish, frustrations and

Undying love in their attempts to make not

Only the masses whole, but themselves as well.

I have observed that for those who became a

Part of the Panthers, life is no longer

Meaningless. They find purpose, and that

Purpose is restoring human dignity and pride

To a decadent society and world.

When one reaches this level of understanding, in most cases, it is an

indication that one is not only in the

Process of dealing with himself but that

He has become aware that he is a part of the whole of humanity / He

has made progress in his search for identity ...

REV. JULIUS THOMAS

Contents

Introduction:

Painting a More Complete Portrait of

the Black Panther Party

Judson L. Jeffries and Ryan Nissim-Sabat

Judson L. Jeffries

2. Picking Up Where Robert F. Williams Left Off:

The Winston-Salem Branch of the Black Panther Party

Benjamin R. Friedman

Ryan Nissim-Sabat

4. Nap Town Awakens to Find a Menacing Panther;

OK, Maybe Not So Menacing

Judson L. Jeffries and Tiyi M. Morris

5. Picking Up the Hammer:

The Milwaukee Branch of the Black Panther Party

Andrew Witt

6. Brotherly Love Can Kill You:

The Philadelphia Branch of the Black Panther Party

Omari L. Dyson, Kevin L. Brooks, and Judson L. Jeffries

Judson L. Jeffries and Malcolm Foley

Conclusion:

A Way of Remembering the Black Panther Party

in the PostBlack Power Era:

Resentment, Disaster, and Disillusionment

Floyd W. Hayes III

COMRADES

Judson L. Jeffries and Ryan Nissim-Sabat

T he Black Panther Party (BPP) was different than any other radicalgroup of its era. The BPP was not merely an organization; it was a culturalhappening. Panther posters donned the walls of left-wing activists and radicalthinkers all over the world, and their buttons were worn by activists in France,Sweden, China, and Israel, among other places. Although whites werenot allowed to join the BPP, white supporters, sympathizers, and hangers-onwere substantial in number. When Huey P. Newton was arrested for themurder of a police officer, the Partys legend appeared to grow exponentially.Released in 1970 after serving nearly three years in prison, Newtonwas greeted by hundreds of cheering and adoring onlookers, many of whomwere white. The memoirs, newsletters, and interviews of activists around theworld bear testimony to the Partys transatlantic impact. The BPP was not amere organization, but a movementthe likes of which has not been witnessedsince.The first glimpse the country got of the Panthers was in May 1967 whenthe group staged its dramatic protest at the statehouse in Sacramento, California, a spectacle that electrified the nation. Almost immediately peoplewere transfixed by the Panthers bold and public display of defiance. They hada swagger seldom seen before, as if they were saying to white America, Lookhere, Black people arent gonna take this s_ _t anymore. No more of this turnthe other cheek stuff. We, the Black Panther Party, are here and ready todeal with you (the oppressor) anytime, anywhere. America didnt just look;it stared. In Oakland, people stared as Panthers prowled the streets intent onmaking police officers think twice about manhandling Bay Area Blackssomething to which they had become accustomed. People stared as Huey P.Newton, a baby-faced militant with a high-pitched voice, grew into a larger-than-lifefigure even before he figured out that in the minds of many he hadbecome a savior of sortsa cultural and political icon. People stared at andlistened to Eldridge Cleavers fiery, spellbinding indictment of the imperialistMother Country and how her avaricious lapdogs oppressed and exploitedpeople of color all over the world. To some whites, the Panthers were a bunchof Nat Turner reincarnates in berets and black leather jackets. Many whiteserroneously thought that the Panthers wanted to do to them what whites hadhistorically done to Blacks. On the contrary. The Panthers were not Blacksupremacists nor were they interested in exacting revenge on the white racefor slavery or Jim Crow, but unfortunately, these are the types of images thathave come to symbolize the Black Panther Party and its history. Oftentimeswhat gets lost in the writings and discourse about the BPP is the mundanegrunt work done by local Panther activists across America. The BPPs historyis robust and nuanced. Whats moreit has largely been untold.

The Black Panther Party was arguably the only Black international revolutionaryorganization that consistently challenged the conditions of Blacks aswell as poor people generally in the United Statesa point too often unacknowledged.The government called the Party subversive and un-American.Not so. A close and more objective look at the Panthers reveals many of themto be patriots. Many of the Panthers served in the United States militaryand several fought in the Vietnam War. Some served with distinction andearned Bronze Stars and Silver Stars as well as the Purple Heart. Like manyAmericans, some Panthers went to war because they thought America wasworth fighting for. When they returned home they fought against the practicesof the U.S. government because they believed the country had lost itssoul. But more importantly, they believed it could be redeemed. As ReginaldMajor pointed out, the Panthers were soldiers at war in the jungle which isAmerica, warriors moving to bring greatness to the American Experienceby completing the work begun by the revolution of 1776.1