Table of Contents

For the ancestors, Eleanor Conway and Wilhelmina Hayes, and the children.

Prologue

The Court: Mr. Conway, Im going to warn you right now on the record that unless you behave yourself

(The remainder of the Courts remarks inaudible because of the defendants interruption.)

The Defendant: Behave myself ? I want an attorney of my choice. What you mean, why dont you behave yourself? You said I could have an attorney of my choice. I give you a name and youre going to tell me behave myself and give me somebody who you hope to participate in the railroad job.

The Court: Mr. Conway, would you allow me to make one statement? That is thisIm formally advising you and warning you that if you persist in this conduct, the trial will go forward without you. You will remain outside of the courtroom.

The Defendant: The trial will go forward without me if you dont let me have an attorney of my choice. If youre going to give me an attorney that I dont desire to have on a homicide charge, then the trial will go forward without me, because Im not going to participate in it, because I have an attorney of my choice, and you will not allow him to be here. So its your trial.

The Court: All right. Now would you care to be seated, or do you wish to leave the courtroom?

The Defendant: Right. I wish to leave the courtroom. (Holds hands up to be cuffed.) Look, the man asked me did I want to go. I want to go.

The Court: All right.

The Defendant: Look, Im not going to be taking part in this madness.

Hey Conway. I heard the floor supervisor say my name before I saw him.

Report to the supervisors office ASAP.

I was working the night shift at the main post office in Baltimore, a stretch of time that spanned eleven at night to seven in the morning. It was 1970, but the work was still much like picking cotton: rows and rows of black faces tossing mail into boxes, while a white man stood by, supervising the whole process. Workers could talk to each other on the line as long as they kept the mail moving and met their quota, but they had to ask permission from the supervisor to go to the restroom. The workers who the supervisor identified as rebellious, who also happened to be mostly black, were placed in an area of the post office called parcel post. This is where I spent most of my time, and it was real grunt workheavy boxes that required sorting before we tossed them into large hampers. It had always reminded me of the stories I had heard of the days when the more unruly black slaves were sold further south, where the labor and conditions were more strenuous.

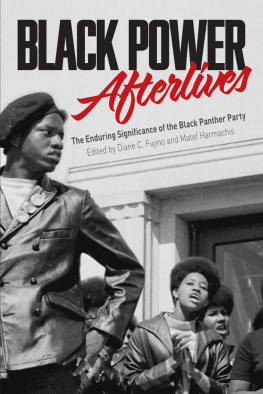

It was because of conditions like these that some of us had begun to organize a union for black workers. We felt that the existing postal union wasnt representing our needs and concerns. I was a key organizer of the new union, and as I walked down the hall to the supervisors office, I mentally prepared myself to step through his door and be read the riot act for my organizing work. As a member of the Black Panther Party, I had begun to expect these situations, but at that moment, I never could have foreseen the aggression that the government would employ to dismantle our movement. We were simply outgunned and outnumbered, just as I was at that moment when I walked into the office and found myself facing five white men with .38 caliber revolvers pointed directly at my chest. History holds true that this has never been a good situation for a man of African descent. I tried to maintain my cool as I scanned the room and sized up the situation, but as the men tightened the handcuffs around my wrists, I resigned myself to the fact that there was nothing I could do.

I initially thought that federal agents were abducting me because of my affiliation with the Black Panther Party, so I was determined to keep my wits about me while I tried to assess the situation. Most of us in the party leadership in Maryland had been aware of warrants for our arrest for various charges for at least the past six months. I had also become increasingly aware of the harassment and scare tactics that the government used to discredit and derail our efforts at organizing in our communities. Yet, I still didnt have a clue when these plainclothes officers took me to Central Booking at the Baltimore City Jail and charged me as an accessory to murder in the case of a missing informant.

So began what would become an odyssey of indeterminate time. After nearly four decades in Maryland prisons, if I walked out tomorrow it would not end there. I was railroaded, plain and simple, and nothing can reclaim for me the time that was lost. Denied a lawyer of my choice and saddled with a court-appointed attorney whose greatest arguments had probably taken place in the barrooms of Baltimore, I knew the outcome before the verdict was handed down, and somewhere deep within my soul, I suspected it would span a lifetime. I have done this time without looking back. The years in prison, like dog years, have passed at a dizzying rate, each day flowing like a decade. And during this time I have done the only thing that I could dokeep moving forward.

Imprisonment is slavery and the enslavers have long been opting to pack the ships as tightly as possible. Block after block of this nations prisons are overflowing with black and brown bodies. And after thirty years of capturing the strongest of the stock, the system now satisfies itself with our children. I am confined with young men and boys who could be my grandsons. These are youth who, prior to their imprisonment, looked to fathers and brothers and uncles for leadership only to find that, in many cases, they were already gone to the jails, the streets, or the grave. They come from mothers who have also been locked up or are frequently overburdened with basic survival issues: how to pay rent and utilities, how to feed their families, and so on. Some of them even come from middle-class backgrounds, but the common denominator is race. Most tend to be the descendants of enslaved Africans. The prison system renders the confined individual powerless, causes the separation, and in many cases dissolution, of families, and provides a labor force that in the present economy is akin to slave labor. Over time, the trauma of incarcerationbeing snatched away from family and communityinterferes with the memory, and even though we may still recall our families and our friends, they slowly fade to little more than ghostlike figures in the shadows of our minds.

From the very moment that the cell door slammed shut, I knew it would be my responsibility to resist just like my enslaved ancestors in Virginia must have resisted. At times, that resistance would become more important than my actual innocence, for it was this determination to resist white supremacy that led to my imprisonment in the first place. Just as slavery led to the creation of the Underground Railroad, prisons have necessitated the development of a similar system comprised of relationships and routes that help the prisoner escape the inhumanity of incarceration. I have managed to hold on to my humanity for four decades now only because of the support from my family and my community, because they help me to remember that I am human.

During the trial there were always so many people at the jail that sometimes when I went to visit I couldnt even get in. These words spoken by my mother, Ms. Eleanor Conway, thirty-eight years later are not tinged with bitterness so much as an air of regret. I am also regretful. Many people see me only through a political lens, but I am a human being, with very human relationships, yet borne of a mother who understands that I belong more to the world than her. My mothers eyes used to cloud over when she talked about the hand that I was dealt: I never thought Eddie would still be there all these years. And I never thought I would still be here forty years later when I received word of my mothers death.