Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

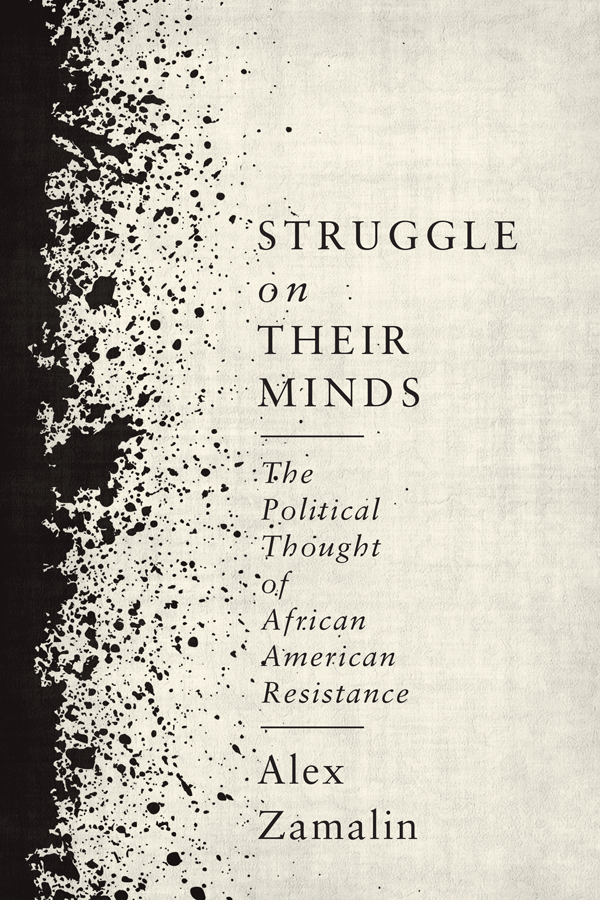

STRUGGLE ON THEIR MINDS

STRUGGLE ON THEIR MINDS

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT

of

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESISTANCE

ALEX ZAMALIN

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54347-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zamalin, Alex, 1986 author.

Title: Struggle on their minds : the political thought of African American resistance / Alex Zamalin.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016057013 (print) | LCCN 2017018783 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231181105 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansPolitics and government. | African AmericansPolitical activityHistory. | African American intellectuals. | Walker, David, 17851830Political and social views. | Douglass, Frederick, 18181895Political and social views. | Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 18621931Political and social views. | Newton, Huey P.Political and social views. | Davis, Angela Y. (Angela Yvonne), 1944Political and social views. | African AmericansIntellectual life. | SlaveryUnited StatesInfluence.

Classification: LCC E185.615 (ebook) | LCC E185.615 .Z35 2017 (print) | DDC 323.1196/073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016057013

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: FaceOut Studio

FOR ALISON, SAM, AND ANITA

CONTENTS

I have been fortunate to receive support from many people. I would like to thank my editor, Wendy Lochner at Columbia University Press, for her constant enthusiasm for the project, as well as three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback, which substantially improved the quality of the final manuscript. I would like to thank my colleagues at University of Detroit Mercy for providing support and encouragement throughout the process, especially Stephen Manning, Genevieve Meyers, Rosemary Weatherston, Amanda Hiber, Mary-Catherine Harrison, Megan Novell, Karl Ericson, and Sigrid Streit. I am particularly grateful to Michael Barry and Nick Rombes for taking time to offer incredibly helpful suggestions that informed the scope and some of the animating ideas in the book. My students at UDM provided the first testing ground for many of the books arguments, and I am grateful for their enthusiasm. For research assistance, I would like particularly to thank Jewuel Boswell and Lydia Mikail.

Beyond UDM, I am also thankful for the encouragement and friendship of Dan Skinner, Jeff Broxmeyer, Mark Navin, and Hunter Vaughan. In addition to reading numerous drafts of the manuscript and providing generous and thoughtful feedback throughout the process, Jon Keller has enriched my understanding of the American political tradition and has helped me become a clearer writer. Max Burkeys influence on the manuscript cannot be overstated. Max always provided an ear to discuss many of the books ideas in its earliest stages, helped refine its final arguments, and has consistently pushed me to be a more expressive and honest writer.

Special thanks also go to my extended family, Arnold Zamalin, Marina Zamalin, Raya Zamalin, Emil Zamalin, Ron Powell, Frona Powell, Aaron Powell, and Liz Powell. Above all, I would like to thank my wife, Alison Powell, who has dedicated endless hours of her life to enriching mine. Her poetry and scholarship continue to inspire me in profound ways, and her companionship and friendship know no bounds. Without her presence in my life, this book would not have been written. My son, Sam, helps me grow day in and day out. His wisdom and endless capacity for finding magic and beauty in the world is truly humbling. My daughter, Anita, reminds me to appreciate the wonder of the unknown. Her smiles brighten my day, and her strength is energizing. It is to Alison, Sam, and Anita that I dedicate this work.

T his book examines the political thought that emerges from the long history of African American political resistance to racial inequality in the United States. This is the story of abolitionists asserting in political manifestos that slavery must be abolished by any means necessary, slaves revolting against their masters, journalists chastising the American institutions that turn a blind eye toward the lynching of African Americans, and radicals policing the police and calling for the abolition of the American prison system. Examining the work of five of the most theoretically significant but still underappreciated African American political resisters and the movements of which they were a partslavery abolitionists David Walker and Frederick Douglass; Ida B. Wells, who was the key figure of the antilynching movement; Huey Newton and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense he helped organize; Angela Davis and the prison-abolition movement Struggle on Their Minds argues that one central dimension of African American resistance has been to revise core values in the American political tradition.

This book challenges the view that the only democratically valuable kind of African American political resistance is one that conforms to the dominant values of American culture. Resistance is often depicted as politically threateningcaptured by the current U.S. Department of Defenses Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms , which defines a resistance movement as an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to resist the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. As a political activity that contests existing constellations of state power, resistance appears to undermine political stability and the rule of law. More often than not, however, the term is demonized, conjuring images of unbridled violent rebellion or militancyfor example, anarchists who called for abolishing the American government and communists who called for an overthrow of capitalism. Those few resistance movements redeemed in the American imaginationand this almost always happens retrospectivelyare redeemed only because they call for gradual political reforms and because they frame their objectives in dominant American values like individualism, limited government, and private property: for instance, suffragettes advocating for womens political rights or labor activists struggling for better working conditions.

The rich history of African American resistance has been viewed in a similar way. Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. havethrough a selective interpretation of their most patriotic writingsbeen elevated to the status of American founding fathers, but many black radicals, such as Martin Delany, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and Audre Lorde, have been dismissed, if not treated with contempt. To make matters worse, a long history of racist narratives about African Americans being angry and disorderly has helped link the idea of African American resistance with criminality. In a certain sense, this has continued today, when, for many white Americans, black resistance often signifies not political agitation but an unwillingness to accept cultural norms of upstanding citizenship and a rejection of the nuclear, male-led family.