Chapter One

PICTURING THE TRUE PERSON

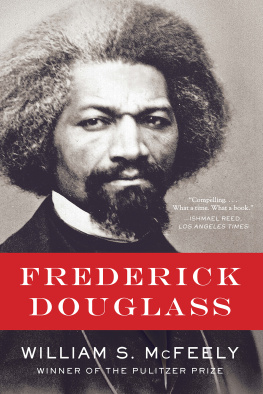

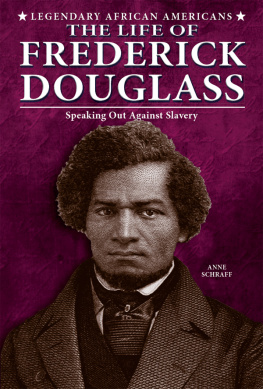

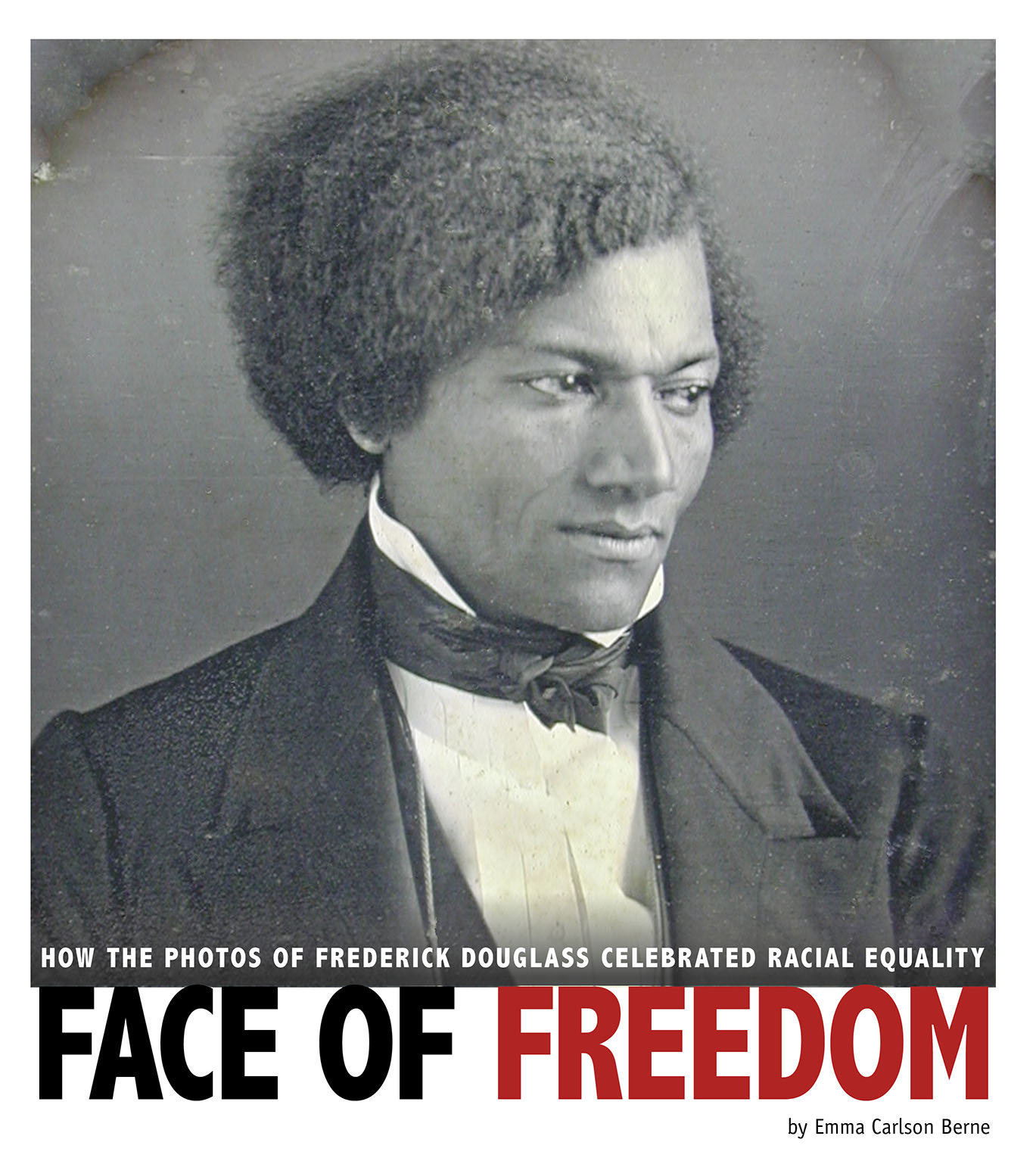

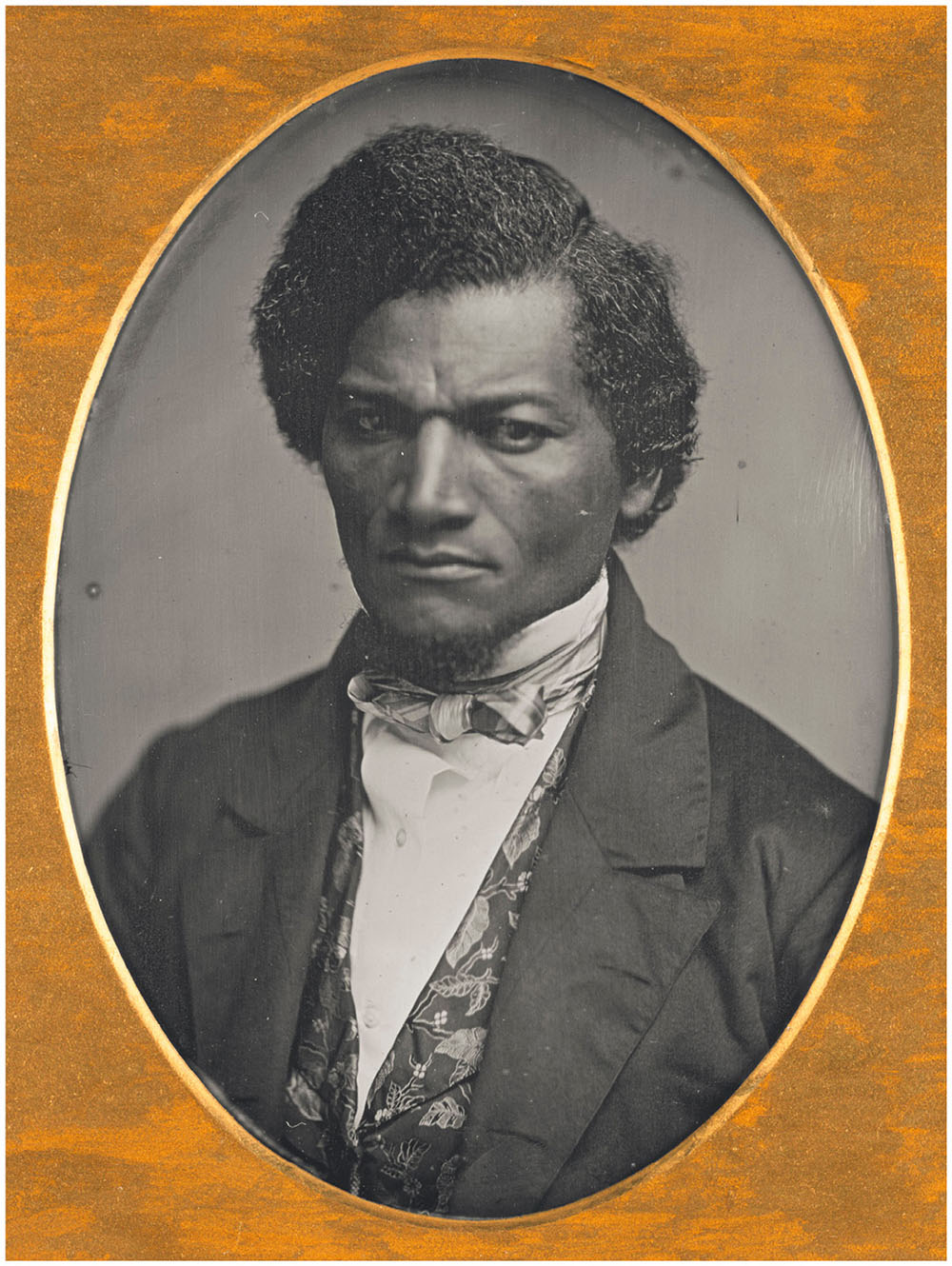

In the spring of 1848, a young black man walked into the photo studio of Edward White in New York City. The young man wanted his picture taken. He was stylishly dressed in a crisp starched shirt and collar, a silk necktie, a vest and a fine black coat. His hair was neatly combed. He was a confident, striking presence, but when he sat for the portrait, he did not meet the cameras gaze. He looked away.

Ten years earlier, Frederick Douglass had been a slave. He had been taught that he was no one, not a real person. He had always refused to believe that. But even now that he was free, showing power was sometimes hard for him. Facing a camera head-on was a powerful thing to do. The past still laid a finger on his shoulder.

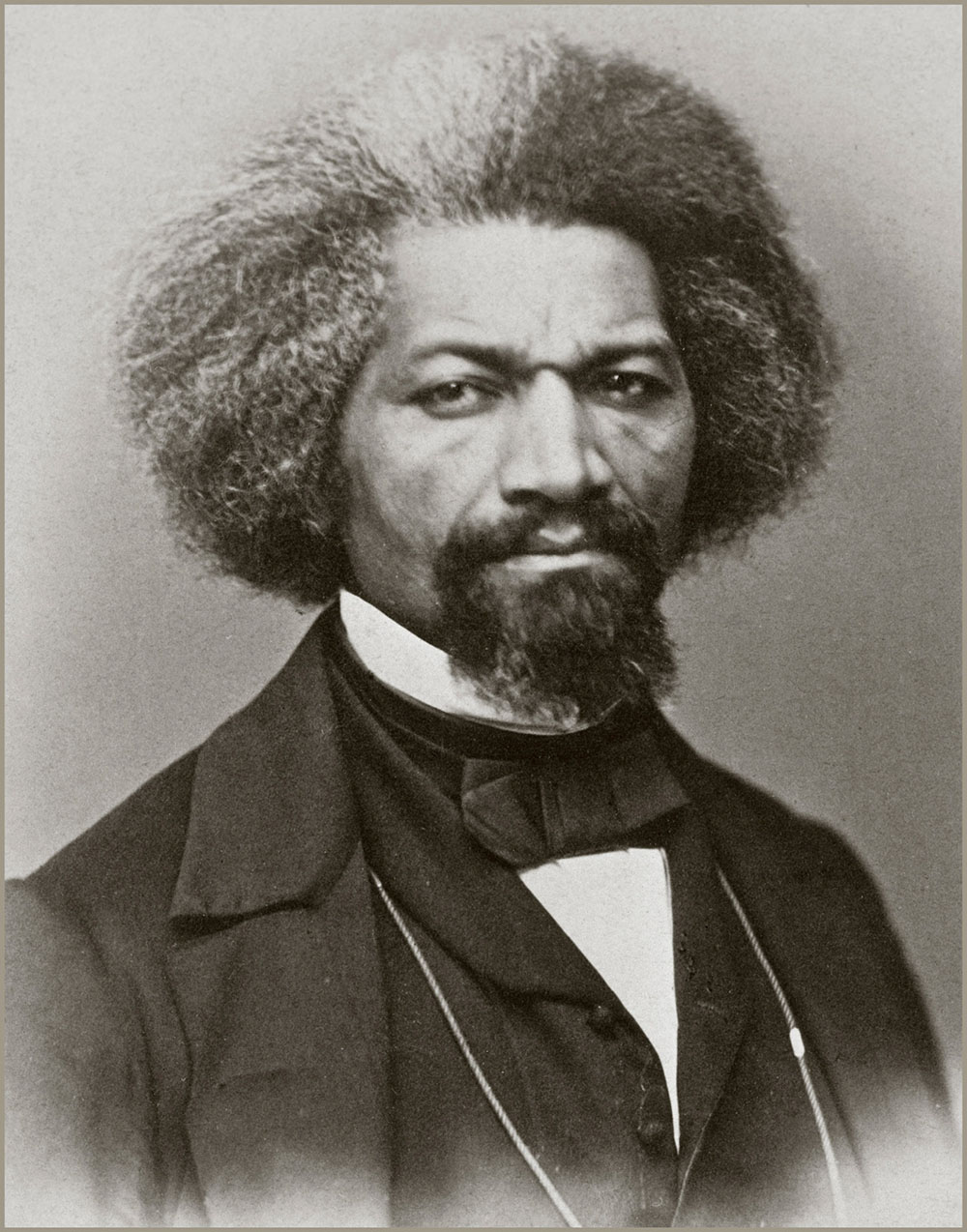

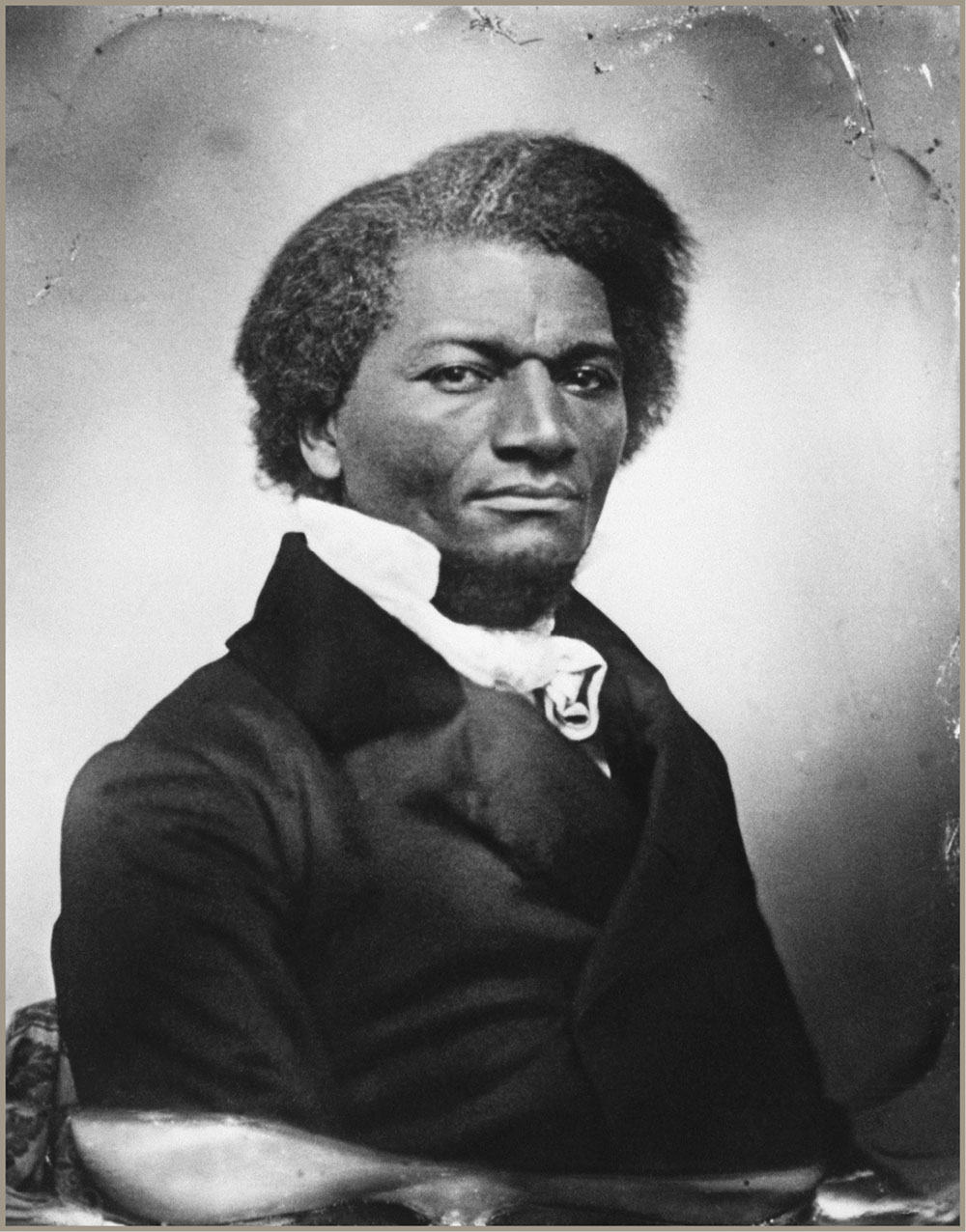

Frederick Douglass was photographed in 1862 by his friend John White Hurn. Douglass was in Philadelphia to give a speech on the Civil War.

It is January 1862. Freezing winds whip the streets of Philadelphia. The United States is in the grip of the escape the United States when the authorities threatened to arrest him for aiding in domestic terrorism. Now Douglass sits for Hurns camera. Again, he wears a fine shirt and cravat. His pose is powerful, commanding. His mouth is set, his eyes are calm and level. His hair is streaked with white now, worn long. He reminds the viewer of a lion, waiting and watching.

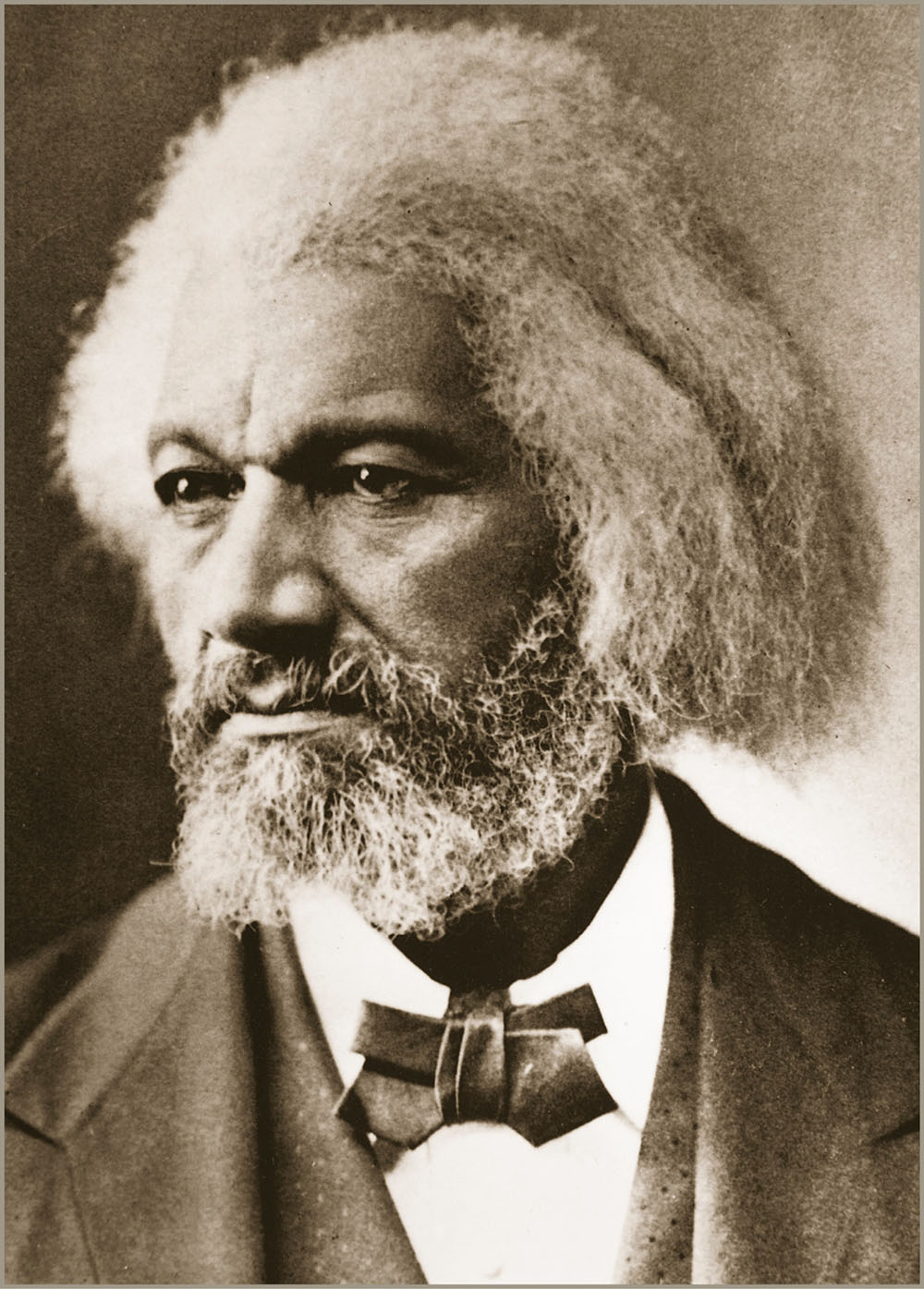

Fast-forward to 1877. The lectures. He has a political appointment he is the U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia. Some say he has forgotten that black people still struggle. But he might say he has become more practical in his old age.

Douglass visited Mathew Bradys Washington, D.C., studio in 1877. Brady was the best-known photographer of his day.

Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century. From his first photo in 1841 to his deathbed photograph 54 years later, he sat for 160 photographs and Abraham Lincoln, who had 126 photographs taken.

Before the mid-19th century, people mostly had their images captured in paintings. Expensive and rare, such pictures were only for the rich. But the daguerreotype changed all that. This early form of photography was inexpensive and easily accessible. Studios cropped up in almost every town and city, and for 25 cents (about $7.50 in todays currency), anyone could have his or her portrait made.

For Douglass, photographs were a democratizing art form.

Douglass escaped captivity in 1838. Coincidentally, the daguerreotype became much more widely available around the same time. This timing was not lost on Douglass. In his speeches, he linked the birth of his freedom with the birth of photography. He considered photographs powerful truth-tellers. Douglass lived in a world in which black people were almost always depicted in drawings or cartoons as stupid, evil, or silly, or as equivalent to animals, such as monkeys. No one portrayed the black form with dignity or humanity. Certainly no one portrayed black men and women as powerful.

The drawings and cartoons of this time that showed black people are upsetting to the modern eye. In a supposedly humorous entitled Grand Football Match-Darktown Against Blackville, monkeylike people with very dark skin are jumbled together in a heap, looking confused. The implication was, of course, that black people were some sort of animal-human hybrid who were not intelligent enough to understand the game. Another picture, a political advertisement, shows two political candidates, for and against allowing black people to vote. The white candidate is shown as sober and neatly groomed. He is wearing a serious expression and a jacket, collar, and tie. The black candidate is depicted with exaggerated facial features, uncombed hair, a mussed, wrinkled shirt, and a silly expression.

DAGUERRE AND EARLY PHOTOGRAPHY

The makers of todays digital images and the photographers of the 20th century owe a great debt to Louis Daguerre, who was a French painter and printmaker. Daguerre spent years with his partner, Nicphore Nipce, working on a problem no one had yet solved: how to capture an image on a surface, using light and chemicals.

Primitive early cameras had existed for centuries at that point. They were called cameras obscura, and they could project images onto paper. People could trace the images but how to capture them permanently?

Nipce figured it out partially. He dissolved a substance called bitumen in lavender oil and managed to capture an image. But the process was cumbersome, inconsistent, and difficult to reproduce. Enter Louis Daguerre, who performed countless experiments, fiddling and fiddling, until by the 1830s, working alone (Nipce had died), he had managed to develop a consistent, reproducible process for capturing images. Daguerre would coat a thin sheet of copper with silver and sensitize the silver-plated sheet with iodine vapors. After exposing the sheet using a box camera, he would develop the image using mercury fumes. The image was stabilized using salt water.

The process was a big success. But like almost any invention in its early stages, it wasnt without drawbacks. Each daguerreotype was unique, which meant it could not be repeated. There was no way to make copies. And the exposure time was terribly long the subject had to remain still for five to 30 minutes. Moving would blur the image. For this reason, many early daguerreotypes are pictures of objects instead of people.

In the 1840s others figured out how to reduce exposure times. Variations on the daguerreotype, such as the , were invented. But Louis Daguerre had done it first, and photographers have owed him a debt ever since.

An 1852 daguerreotype of Douglass, taken in Ohio

It was precisely such insulting images that Douglass sought to refute with his own regal portraits. Photographs could show the true person, Douglass believed. In fact, he thought, they alone were an accurate picture of the man.

Photography could also tell the truth about the horrors of slavery, Douglass believed. Many in the South had a strong belief that slavery was a kind and helpful system, there to help black people who were inherently inferior to white people. Douglass thought photographs forced the viewer to confront the equal humanity of the black person.

In addition, the very accessibility of photography underscored its necessity, according to Douglass. The southern states were sparsely populated and mostly ruralphotography was less available there than in the more developed, more urban North. In addition, the southern slave states had more restrictions on free speech and free press, which included photographs. The northern states had no such restrictions.

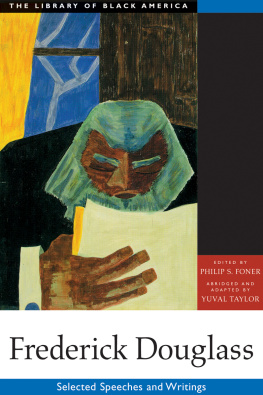

Frederick abolitionist beliefs. And just as he told stories about his life, he used his own person as an art form. His portraits were a form of expression as much as his words.