Translated by Olga Marx

Foreword copyright 1991 by Chaim Potok

Copyright 1947 by Schocken Books Inc.

Copyright renewed 1975 by Schocken Books Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

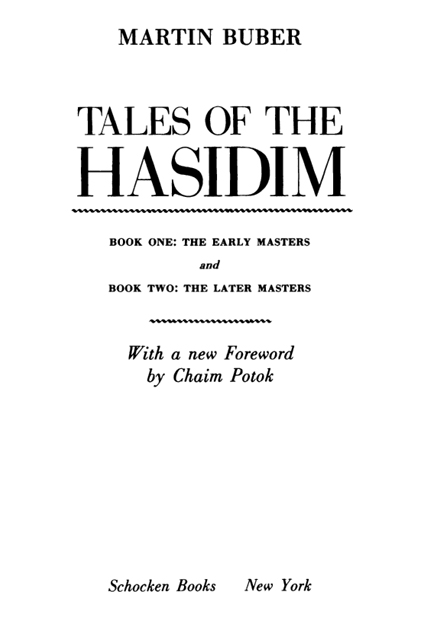

This work was originally published in two separate volumes, Tales of the Hasidim: The Early Masters and Tales of the Hasidim: The Later Masters (Ten Rungs: Hasidic Sayings) by Schocken Books Inc. in 1947.

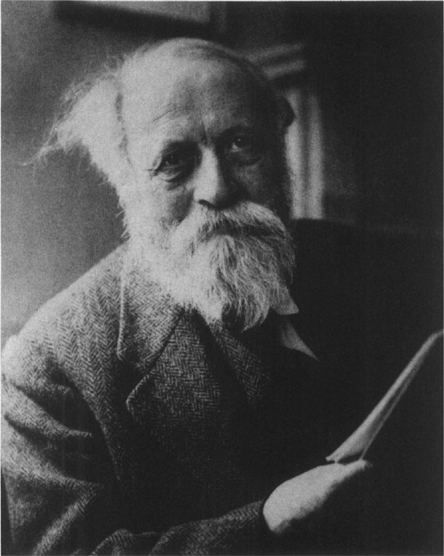

Frontispiece courtesy of Pictorial Parade

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Buber, Martin, 18781965.

[Erzhlungen der Chassidim. English]

Tales of the Hasidim/by Martin Buber; foreword by Chaim Potok.

p. cm.

Translation of: Die Erzhlungen der Chassidim.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. HasidimLegends. 2. Parables, Hasidic. 1. Title.

BM532.B7613 1991 296.8332dc20 90-52921

eISBN: 978-0-307-83407-2

v3.1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by Chaim Potok

Martin Buber, one of the commanding Jewish thinkers of the twentieth century, came to hasidism and its tales in an odd way. The seeds of a lifetime quest are often deeply planted and not easily unearthed. But beginnings can never be entirely buried, and Bubers later interest in hasidism may have originated during his childhood and early adolescence when, because his parents were divorced, he lived in Lemberg with his grandfather, who was an enlightened, renowned scholar and editor of classic rabbinic texts, and at the same time a well-to-do banker, a Jewish communal leader, and a devout Jew, who prayed in a small hasidic synagogue from a prayer book dense with mystical discourse.

Beyond that speculation is the fact that the gathering strength of the sciences at the turn of the century sparked a reaction among some Western European intellectuals: a renewed interest in mysticism. Bubers intellectual idols in the University of Vienna, which he entered in the summer of 1896, were not only the philosophers Schopenhauer and Nietzsche but also the Christian mystics Jakob Bhme, Meister Eckehart, and Nicholas of Cusa. Certain questions haunted Buber from early on. Often we feel ourselves alternately connected to and separated from the world around us. Does the sense of alienation lie at the very root of the human condition? Does it give rise to the mystical yearning for unity with the world and God? Is there a real unity out there somewhere waiting to be discovered by us? Can we realize it, kindle it into existence, by leading authentic, open, honest lives? Can God be realized, made actual, through man?

Buber grew up in an age when Jewry experienced the full power of the secular enlightenment, the subsequent marshaling of Orthodox forces in opposition to secularism, and the birth of modern political Zionism. Newly emancipated Jews, heady with the prospect of participating as partners in Western civilization, attempted to enter fully the mainstream of European lifesome by denying their inherited culture, others by taking with them a personal vision of it into the wider world. Those who broke entirely with Judaism and for one reason or another chose later to return, often did so on their own terms. Gone forever was the time when an apostate, like the seventeenth-century Amsterdam Jew, Uriel da Costa, would return unconditionally and at the cost of public contrition and humiliation to the faith established and maintained by repressive communal elders.

The First Zionist Congress, held in Basle in 1897, brought Buber back into the Jewish community. Until then he had lived, as he put it, in the world of confusion, the mythical dwelling place of the wandering souls in versatile fullness of spirit, but without Judaism, without humanity, and without the presence of the divine. He returned as a Western Jew, who had broken with Jewish observance during adolescence but had retained a deep awareness of the extent to which Western notions of the individual and the community were rooted in the Bible and the Hebraic tradition. In 1901 he joined the staff of the Zionist periodical Die Welt, and though he left shortly thereafter, he remained involved in Zionist activity.

He described his odyssey of return in My Way to Hasidism. The Hebrew he had learned as a boy and subsequently neglected he now relearned and enriched. He began to grasp the language in its essence gradually overcoming the strangeness, beholding the essential with growing devotion. And then one day, in his twenty-sixth year, he experienced a remarkable event.

I opened a little book entitled the Zevaat Ribeshthat is the testament of Rabbi Israel Baal-Shemand the words flashed toward me, He takes unto himself the quality of fervor. He rises from sleep with fervor, for he is hallowed and become another man and is worthy to create and is become like the Holy One, blessed be He, when he created his world. It was then that, overpowered in an instant, I experienced the Hasidic soul.

Acting on that experience, he withdrew from Zionist activity and for the next six years retired into the stillness. He began to gather not without difficulty, the scattered, partly missing, literature and immersed himself in it, discovering mysterious land after mysterious land.

The mysterious land he discovered was the mystical terrain of hasidism.

There had been hasidim, individuals of exceptional piety, in the Talmudic period, and a hasidic community of sorts had existed for a while in medieval Germany. Modern hasidism is the child of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer of Mezbizh, known as the Baal Shem Tov, Master of the Good Name (17001760). He was, it appears, a man both learned and charismatic, a folk healer, one of those who went about curing the sick by invoking the various mystical names of God. Concerning his life, words, and deeds, we have only legendsin shards of writings, tales, pamphlets, books that purport to recount his actual teachings but are clearly infused with excesses of piety and invention.

Hasidism was an explosive act of creation: a response by a single person to the cry of the masses.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, after a decade of rebellion by Ukrainian peasants against their Polish overlords and a subsequent war with Sweden, in both of which Jews were made to suffer brutally, the once vital Jewish community of Poland was in ruins. In response to this crippling, the world of Polish Jewry turned in upon itself and became so rigorously restrictive and hermetic as to drain it of the possibility of creative spontaneity. The Jewish community lay in a torpor of congealed ritualism; and its most esteemed activity, the learning of Torah, became abstruse, elitist, and far removed from the grim realities and miseries of everyday existence.

Grinding poverty, endless sufferingand learning as the only avenue to God. An ideal mix for revolution. Conjure the bitterness and frustration felt by ordinary unlearned Jews in a culture entirely focused on learning. If learning is the exclusive path to God, how does one come to God when one is a shoemaker, a wagon driver, a water carrier; when one must work day and night and has little time for study?