MARTIN BUBER

Martin Buber

A Life of Faith and Dissent

PAUL MENDES-FLOHR

Copyright 2019 by Paul Mendes-Flohr.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956107

ISBN 978-0-300-15304-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

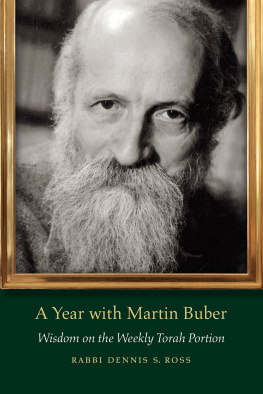

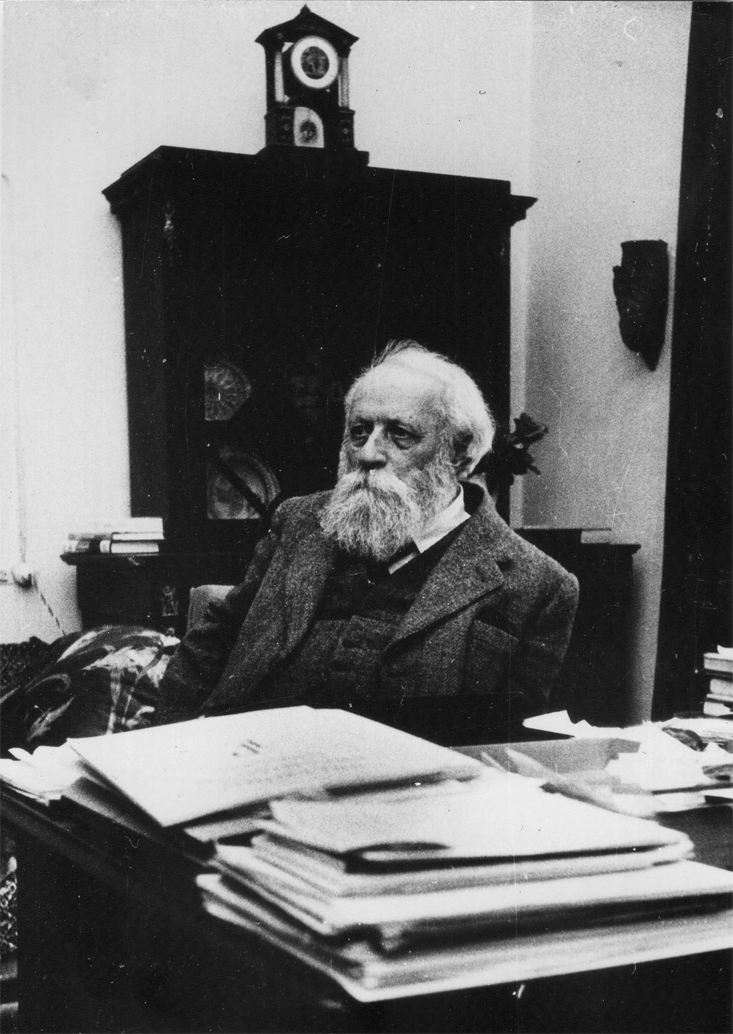

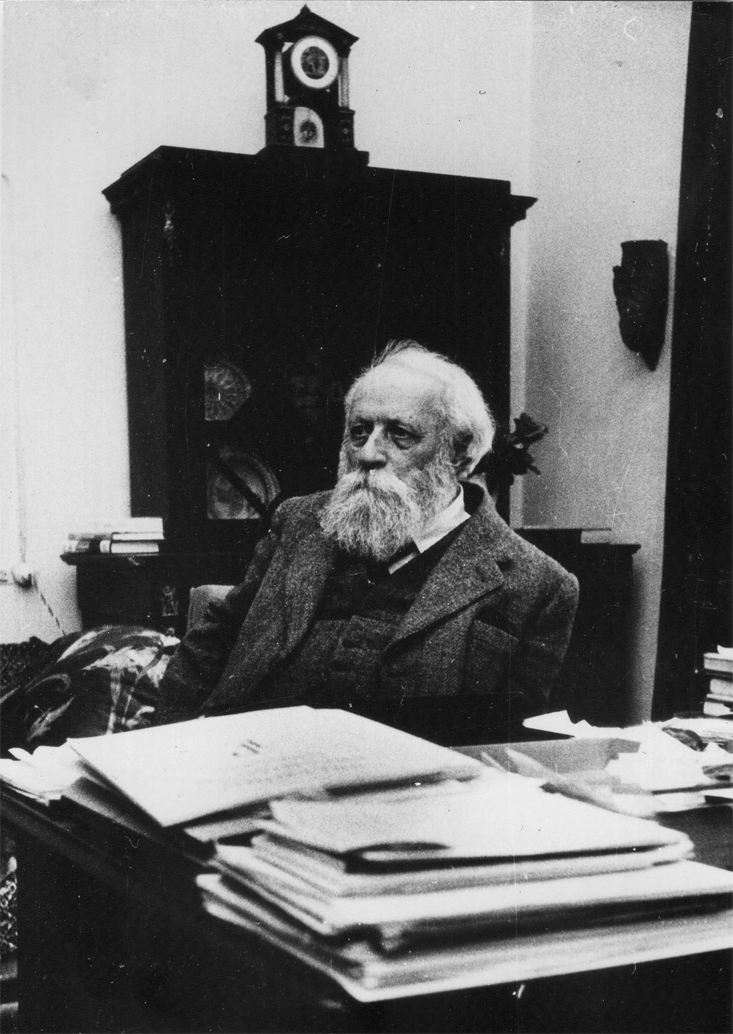

Frontispiece: Martin Buber in his Jerusalem study, 1963.

Courtesy of the Martin Buber Literary Estate.

ALSO BY PAUL MENDES-FLOHR

Wissenschaft des Judentum: History and New Horizons (editor, with Rachel Freudenthal)

Dialogue as a Trans-Disciplinary Concept (editor)

Gustav Landauer: Anarachist and Jew (editor, with Anya Mali)

Progress and Its Discontents: Jewish Intellectuals and Their Struggle with Modernity (Hebrew)

The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History, 3rd rev. ed. (with Judah Reinharz)

Contemporary Jewish Thought, 2nd ed. (with Arthur A. Cohen)

A Land of Two Peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs

German-Jewish History in Modern Times, vol. 4: Renewal and Destruction, 19181945 (with Avraham Barkai)

Martin Buber: A Contemporary Perspective

German Jews: A Dual Identity

Martin Buber Werkausgabe (editor-in-chief, with Peter Schfer and Bernd Witte)

For Rita, our children, and our grandchildrenand my students, past and present

CONTENTS

Illustrations follow

INTRODUCTION

I am unfortunately a complicated and difficult subject.

Martin Buber

C OMMENTING ON her own intellectual biography, Hannah Arendt noted, I do not believe there is any thought process without personal experience. Every thought is an afterthought, that is, a reflection on some matter or event.

All these challenges are certainly faced by any biographer of Martin Buber. Writing did not come easily to him; as he once confessed to an impatient editor of one of his collections of essays in English, I want you to know for once and all that I am not a literary man. Writing is not my job but my duty, a terribly severe one. When I write I do it under a terrible strain. He would write numerous drafts and continually revise his works from edition to edition, deleting whole passages and rewriting others. While Buber did not always alert the reader of subsequent editions about his revisions, his biographer can consider them hints at possible biographical shifts and intellectual adjustments.

The biographer, as Janet Malcolm observed in her study of Sylvia Plath, is (and I would add, should be) inevitably haunted by an epistemological insecurity. The story a biographer tells is by its very nature interpretive. When assembling facts and evaluating their biographical significance, the biographer often selects those that support the narrative he or she has constructed, in order to provide a coherent story line.

To minimize the inevitable tendentiousness of the narrative I have constructed, I sought to take my clues from Buber himself. The story I tell about his life and thought is shaped by what he relates primarily in his correspondencethe Martin Buber Archive at the National Library of Israel contains over fifty thousand letters between Buber and hundreds of correspondentsas well as in parenthetical autobiographical comments

If one were to write his biography, Buber hence insisted, it should be focused on his thought, taking into account those constitutive moments: My philosophy, he wrote, serves an experience, a perceived attitude that it has established to make communicable. I was not permitted to reach out beyond my experiences, and I never wished to do so. I witnessed for experience and appealed to experience. The experience for which I witnessed is, naturally, a limited one. But it is not to be understood as a subjective one. I say to him who listens to me: It is your experience. I must say it once again: I have no teaching. I only point to something in reality that had not or had too little been seen. I take him who listens to me by the hand and lead him to the window. I open the window and point to what is outside.

Buber was, accordingly, wary of any biography that tried to probe the psychological sources of his ideas and his writings, thereby reducing themand himto a subjective, idiosyncratic, and thus speculative reading. In reply to an American doctoral student who was writing a comparative psychological biography of Buber and Kierkegaard, Buber protested:

I do not like at all to deal with my person as a subject, and I do not think myself at all obliged to do so. I am not interested in the world being interested in my person. I want to influence the world, but I do not want it to feel itself influenced

Bubers views on this issue were multilayered. He once wrote to Franz Rosenzweig that in order to understand why he had rejected traditional Jewish observance, I would have had to tell you about the internal and even external history of my own youth. Still, he would point out, his own struggle with the traditional Judaism in which he was raised resonated with that of his generation of Jews, especially those who also hailed from eastern Europe. Many of his experiences and attitudes should therefore not be considered idiosyncratic or distinctively personal, but representative of those shared by many of his contemporariesexpressions of the complex lived question, born of Jewrys passage into the modern world, of how to continue to identify as Jews.

The story I have chosen to tell about Buber, then, coheres with Edward Saids conception of identity as the animating principle of biography. The biographer seeks to understand a life in a way that reinforces, consolidates, and clarifies a core identity, identical not only with itself, but in a sense with the history of a period in which it existed and flourished.Jew is subject to the vagaries of history and social circumstance. In traditional Jewish society, the quotidian interests of the natural Jew had been subordinate to Israels supernatural calling. But with the Emancipation, the opening of the gates of the ghetto, and access to new social and economic opportunities, the natural Jew gained preeminenceand the attendant struggle against anti-Semitism and for full political equality often led to an eclipse of the supernatural Jew.

As his life and thought evolved, Bubers overarching concern was to reintegrate the natural and supernatural Jew. While unfailingly attentive to Jewish struggles for political and social dignity, he insisted that the politics of the natural Jew, particularly as expressed in Zionism, should be guided by the foundational ethical and spiritual principles of the supernatural Jew. He elaborated these principles under the rubric of biblical humanism (and alternatively, Hebrew humanism), portraying them as sustained by a dialectical balance between the particular and the universal. A Jews uncompromised fidelity to the Jewish people, Buber held, need not undermine his or her abiding cosmopolitan and transnational commitments, and vice versa. In his essay Hasidism and Modern Man, he eloquently affirmed this conviction: It has often been suggested to me that I should liberate this teaching [of Hasidism] from its confessional limitations, as people like to put it, and proclaim it as an unfettered teaching of mankind. Taking such a universal path would be for me but arbitrariness. In order to speak to the world what I have heard I am not bound to step into the street. I may remain standing at the door of my ancestral house: here too the word [resonant with universal significance] that is uttered does not go astray.

Next page