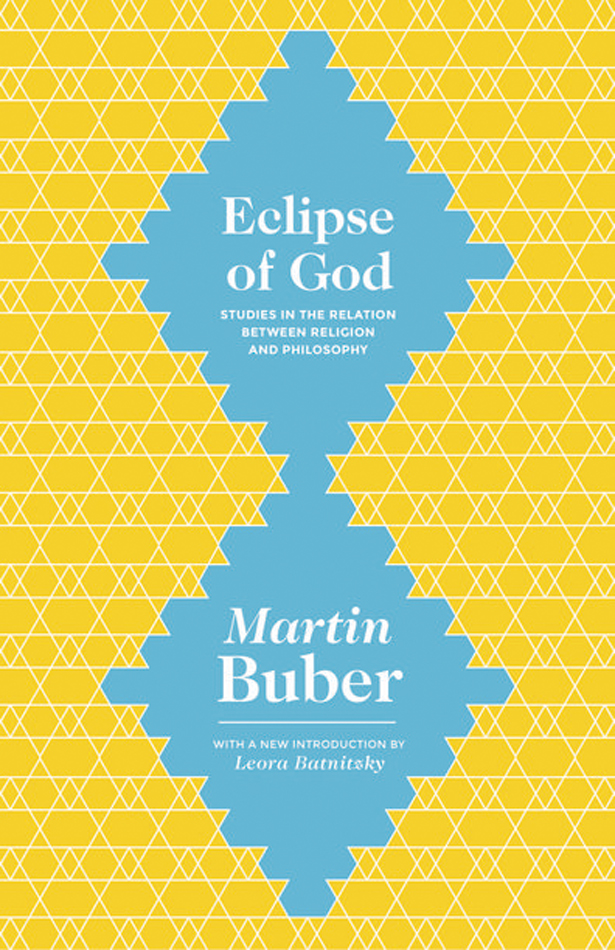

ECLIPSE OF GOD

Eclipse of God

STUDIES IN THE RELATION BETWEEN RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY

Martin Buber

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY

Leora Batnitzky

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by the Martin Buber Literary Estate

Introduction to the 2016 Edition copyright

2016 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Originally published by Harper & Brothers in 1952

First Princeton University Press paperback edition, with a new introduction by Leora Batnitzky, 2016

Library of Congress Control Number 2015938543

ISBN 978-0-691-16530-1

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro, ITC Caslon 224 Std, and Montserrat

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Introduction to the 2016 Edition

Given that this book was first published in 1952, and given its title, Eclipse of God, some readers may assume that this is a work of post-Holocaust theology. It is not. In these essays, Buber does not offer a response to the Holocaust because the eclipse of God, for him, marks not only Gods absence during the Shoah but also Gods absence in the modern world more broadly. The eclipse of God is the Jewish notion of hester panim, which refers to God hiding His face. The term is originally biblical, occurring, for instance, in Deuteronomy 31:17, when God says, And I will forsake them [the children of Israel], and I will hide my face from them, and they shall be devoured, and later in the prophets.

myself and act as an isolated being, unaffected by the greater reality of which I am a part.

This brings us to the eclipse of God. In the essays in this volume, Buber describes God as the primary Thou. God is the greater transcendent reality against which all of human life takes place. The eclipse of God is the eclipse of the possibility of experiencing human life in relation to this greater reality. In this sense, the eclipse of God is also the eclipse of the human. Let us turn to Bubers own words from the second essay of this volume, Religion and Reality:

Eclipse of the light of heaven, eclipse of Godsuch indeed is the character of the historic hour through which the world is passing. An eclipse of the sun is something that occurs between the sun and our eyes, not in the sun itself. But one misses everything when one insists on discovering within earthly thought the power that unveils the mystery. He who refuses to submit himself to the effective reality of transcendence as suchour vis--viscontributes to the human responsibility for the eclipse. (18)

Three points are important here. First, according to Buber, our inability to see God does not mean that God is not there, just as the sun still exists when the moon blocks it in a solar eclipse. Second, seeing Gods reality is not merely a matter of adjusting human psychology, just as seeing the sun during a solar eclipse is not merely a matter of adjusting our eyesight. Finally, just as the moon blocks the sun while in no way destroying the suns reality in a solar eclipse, so too, Buber suggests, something literally blocks our relationship to God in our day. What stands in the way of the human being and God in the modern world?

God is eclipsed in the modern world, argues Buber, by the predominance of instrumentality, the glorification of usefulness, which turns human beings into objects among other objects. Modern political and economic arrangements treat the individual person as an object among others, to be manipulated and regulated by the modern nation-state. Modern science, philosophy, and even religion similarly deny the simultaneous singularity and interconnectedness of individuals. Buber argues that we live in an age in which knowledge and the use of knowledge to control our lives are our dominant values. This means that our relations are relations of usefulness, of instrumentality, and not mutuality. For Buber, we have lost access to Gods primary Thou because I-It relations eclipse our access to I-Thou relations. It is important to be clear, however, that Buber does not think we can or even should dispense with many of the gifts of modernity, such as individual right or modern science. He does not wish to suggest that modern medicine, for instance, errs in its attempt to use scientific knowledge to eradicate disease. Rather, the problem is that the exclusive focus on scientific knowledge and instrumentality blocks, as the moon blocks the sun in a solar eclipse, the possibility of our relationship to God.

Of course, one of the tasks of these essays is to clarify exactly what Buber means by God. It is perhaps best to begin with what Buber does not mean by God. Rebuffing the God of the philosophers, Buber contends that God is not an idea or a metaphysical principle. Instead, God is a presence whom the human encounters in specific places and times. These encounters, like the human beings who experience them, are different from one another. They cannot be captured under any unifying or abstract concept and in fact can only be described in anthropomorphic terms: Anthropomorphism always reflects our need to preserve the concrete quality evidenced in the encounter. This is true of those moments of our daily life in which we become aware of the reality that is absolutely independent of us, whether it be as power or as glory, no less than of the hours of great revelation of which only a halting record has been handed down to us (10).

Buber rejects not only the god of the philosophers generally but also more specifically the claims of his older contemporary, the great neo-Kantian Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen. Cohen, following the medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, insists that the Bibles anthropomorphic descriptions of God must be refused entirely. Like Maimonides, Cohen contends that we can only know God by way of our intellects. Updating Maimonides Aristotelianism with Immanuel Kants claim that God is best understood as an ideal of practical reason, Cohen contends that God can be understood only as an idea. In the essay The Love of God and the Idea of Deity, Buber opposes Cohens twin assertions that God is an idea and that one can only love ideas. Cohen maintains that when one loves another person, what one really loves is the idea of that person. Buber denies that one loves ideas and asserts that love can take place only within the concrete reality of the meeting of two persons in a particular place and time. As Buber explains: the deepest basis of the Jewish idea of God can be achieved only by plunging into that word by which God revealed Himself to Moses, I shall be there. It gives exact expression to the personal existence of God (not to His abstract being) (51).

Next page