I

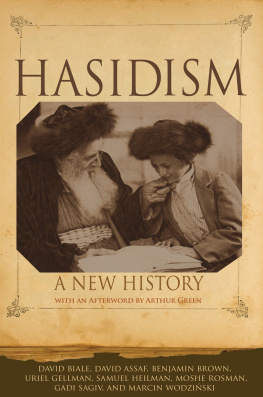

T HE APPEARANCE of Hasidism within the history of faith of Judaism and its importance for the general history of religion cannot be understood on the basis of its teaching as such. Regarded by itself the hasidic teaching offers no new spiritual elements, it presents only a selection, which it has taken partly from the later Kabbalah, and partly from popular traditions among the people. It is true that these spiritual elements have been worked out anew, formulated anew, shaped into a new unity; but also the point of reference which determined this selection is not a theoretical one. The decisive factor for the nature and greatness of Hasidism is not found in a teaching, but in a mode of life; and, indeed, in a mode of life which shapes a community, and regulates a community in accordance with its own character. Here the relationship between the teaching and the mode of life does not at all belong to the type in which a mode of life may be regarded as a carrying out of a teaching; it functions much more in the opposite direction. It is the new mode of life which presses towards a conceptual expression, a theological interpretation; and the practical point of reference, which determines the selection, has its origin in this need for theological interpretation. It is also this relationship which accounts for the fact that the founder of hasidic theology, Rabbi Baer of Meseritch, hardly ever called the Baal-shem, the founder of the hasidic movement, his teacher, although, as Baer himself recounts, Baal-shem had taught him secrets and unifications, the language of the birds, and the writing of the angels; the Baal-shem had no new theologoumena to communicate to him, but a living relationship with this world and the upper world. The Baalshem himself belongs to those central figures in the history of religion who have done their work by living in a certain way, that is to say, not starting out from a teaching but aiming towards a teaching, who have lived in such a way that their life acted as a teaching, as a teaching not yet translated into words. The life of such people stands in need of a theological commentary; their own words form a contribution towards this, but often it is only a very fragmentary contribution; sometimes their words can be used only as a kind of introduction, for according to their original purpose these words are not interpretations but expressions of their speakers lives. In the words of the Baal-shem which we know (as far as we can regard them as correctly handed down) the importance is not found in their objective content, which can be separated off from them, but in their characteristic pointing to a life. Two different things must be added to this. Firstly the nature of this life is given by the wholly personal mode of faith, and nevertheless this faith acts in such a way as to form a community. Let it be noted: it does not form a fraternity, it does not form a separate order, which guards an esoteric teaching, apart from public life; it forms a community, it forms a community of people; these people continue living their life within their family, rank, public activity, some of them being bound more closely, others more loosely, to the master; but all these people imprint on their own, free, public life the system of life which they have received by association with the master. The determining factor in the whole of this process is that the master does not live alone by himself, or lead a secluded life with a group of disciples, but that he lives in the world and with the world. It is just this living in the world and with the world which belongs to the innermost core of his mode of faith. Secondly, there arises a circle of people within the community, who lead the same kind of life, some of whom have reached a similar mode of life independently of the master, but who, through him, have received the decisive stimulation, the decisive moulding, people in different stages, of very different natures, but all endowed with just the one common, basic trend to carry the teaching on by their lives, until everything they say is but a marginal gloss on it. Each life is a life in itself, for its part forming the community; and it is a life in the world and with the world, and a life which for its part again gives birth, in spirit, to people of the same kind. The flowering period of the hasidic movement lasted as long as both agencies remained active, as long as the forming of communities and the spiritual procreation of disciples who form communities continued, that is, as long as segregation gained no entry, and tradition was not rent asunder; it lasted for about five generations from the Baal-shem. The communities were not by any means communities of human paragons, nor were their leaders the kind of men who would be called saints in Christianity or Buddhism, but the communities were communities, and the leaders were leaders. The Zaddikim of these five generations offer us a number of religious personalities of a vitality, a spiritual strength, a manifold originality such as have never, to my knowledge, appeared together in so short a time-span in the history of religion. But the most important thing about these zaddikim is that each of them was surrounded by a community that lived a brotherly life, and who could live in this way because there was a leading person in their midst who brought each one nearer to the other by bringing them all nearer to that in which they believed. In a century which was, apart from this, not very productive religiously obscure Polish and Ukrainian Jewry produced the greatest phenomenon we know in the history of the spirit, something which is greater than any solitary genius in art or in the world of thought, a society which lives by its faith.

Because this is so, because Hasidism in the first instance does not signify a category of teaching, but one of living, its legend is our main source for understanding it, and its theoretical literature comes only after its legend. The theoretical literature is the gloss, the legend is the text, and that in spite of the fact that it is a legend which has been handed down in a state of extreme corruption, and which it is impossible to recover in its purity. It would be foolish to object that legend cannot transmit the reality of hasidic life. It is obvious that legend is not chronicle; however, to him who knows how to read the legend, it conveys more truth than the chronicle. It is indeed not possible to reconstruct from it the factual course of events, but, in spite of its corruption, it is possible to perceive in it the life-element in which the events have consummated themselves, by which they were received and told with naive enthusiasm, and told till they became legend. Apart from secondary, literary elaborations, which betray themselves as such at first glance, no arbitrariness is felt in these tales. Those who told them were impelled by an inner constraint, the nature of which is the hasidic life, the pulsating hasidic relationship of leader and community. Even the most daring miracle-stories are not usually the product of mere invention. The zaddik had done what had never been heard of before, with unheard-of power he had laid his spell over the souls of men, they experienced his work as a miracle, they could but tell of it in the language of miracle. It used to be common further to refer to the fact that many of these tales are of much older origin; much of what is told of the masters of the Talmud, we find here again recounted as the acts of zaddikim. But even this grossly unhistorical attitude has its share of truth. The naive mind that experienced the beatific present weaved into it the tradition of the past that was in tune with the presentany thought of forgery was far from the minds of these storytellers, for, after all, the old stories were mostly known to every one. What happened must rather be conceived of as the spontaneous rise of the report that the Rabbi had done anew this or that well-known deed; he acted in such and such a way, not in order to imitate the first doer, but entirely naturally, because there are certain basic forms of good works. How, for instance, could the irrepressible eagerness to help the helpless find a more direct expression than by the Rabbi coming late to communal prayer, because he had to stop on his way to quiet a weeping child? Or how could the inner freedom with regard to possessions be more radically expressed than by the Rabbi declaring all that he owns to be ownerless before he goes to bed at night, so that the burden of sin may remain far from the thieves who might enter in? However, most often one finds that something new and characteristic has come into the stories in the retelling of them. What had been handed down was, according to its very nature, an example of the individual life. In the atmosphere of the community life it became something different.